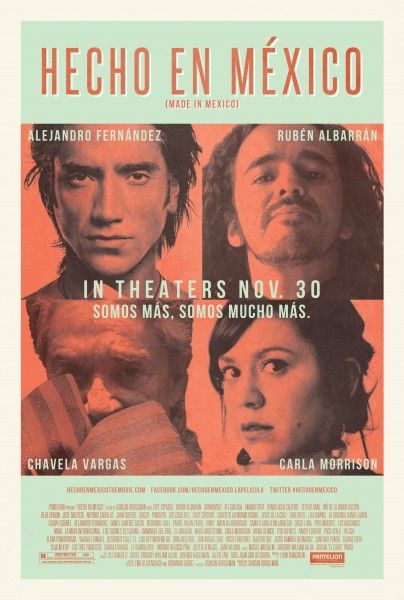

In Hecho en Mexico, Producer/Director Duncan Bridgeman weaves a beautiful and rhythmic cinematic tapestry composed of original songs, conversations, reflections, wisdom and humor featuring many of the greatest performers and sharpest minds of Mexico today. The film showcases the richness of Mexican music both young and old, from traditional music to pop rock and rap, blended with interviews and songs of some of the most popular artists of Latin America. The result is an inspiring and often funny musical road trip that reveals the magic of modern day “Mexicanity” and how it resonates globally. The film, which opened November 30th, features Alejandro Fernández, Diego Luna, Calle 13, Lila Downs, Los Tucanes de Tijuana, among others.

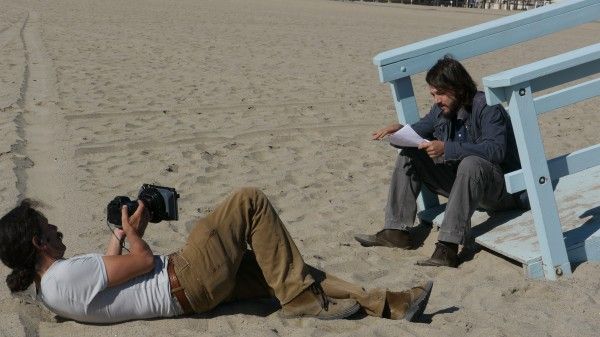

At the film’s press day, Bridgeman and co-producer Lynn Fainchtein discussed what distinguishes their film from traditional documentaries, why they consider it a new form of musical because of its unique narrative structure, how they assembled the impressive group of artists who participated, what it was like shooting in Mexico, how they challenged the traditional notion of what is Mexican and explored a variety of fundamental topics and issues concerning the social and political structure of Mexico, and why it’s significant that Televisa’s Emilio Azcárraga and Bernardo Gómez supported the project. Hit the jump for the interview.

Question: This is not exactly a documentary nor is it narrative fiction, so what is it?

Duncan Bridgeman: I think it’s a new form of musical. It’s not obviously a Broadway musical. We called it a documentary hoping that that might do us better in film festivals, but I think that I’ve come up with a new way of making films. I start with the music, and I put the narrative into the music in musical chunks like 8 bars, 16 bars, which everybody understands. It’s like hip hop, but it’s not rapping, so you get Juan Villoro being a rapper in a way. It’s an art movie, but then we don’t want to call it that because then we’re in the back shelf straight away. (Laughs) It’s like an art musical, man.

What inspired this project and how did you decide which musical artists and groups would be in it?

Bridgeman: The weird thing about it is, I didn’t choose to go to Mexico. I was invited there by Bernardo Gómez (Bernardo Gómez Martinez, executive vice president of Grupo Televisa and one of the film’s executive producers) because he’d seen my last film (1 Giant Leap: What About Me?) and he liked that style of doing what I was doing. He said, “Come and do your stuff here. Work with Lynn. Find the stuff that nobody’s really seen.” So obviously, we needed Kinky and Gloria Trevi and Los Tucanes (de Tijuana) and those names. Luckily, because of Lynn’s experience in the film business, when she calls, people take the call. It was amazing that people trusted us, because we didn’t have a storyboard or a script, and you could have easily been shown the door. But, people got it. That’s amazing testament to the creative individuals in Mexico that they went, “Okay. Go on. We’ll give that a go.” Then, obviously, we looked at everybody who was happening in Mexico at the moment on YouTube, and Lynn threw me stuff, and the rest of my crew threw me stuff, and I was like, “I want to meet that person.” And then, often, like with Meme (del Real Díaz) from Café Tacuba, who wrote the song with Alejandro (Fernández), and he’s in there with Natalia (Lafourcade) in the forest, and he’s there with (Rubén) Albarrán in the shop window, he led us. He said, “Look, you’re missing something. You need to go meet Albarrán.” He brought him in, and then Juan Ciererol as well. So, although you think you’re planning everything, you just do your best, and then usually something unexpected happens, which is the treat. Suddenly, you’re on a hilltop playing drums with Alejandro Fernández and having the time of your life.

The film is beautifully shot and the photography is amazing. What was the experience like shooting in Mexico?

Bridgeman: We used a little Canon 5D which was great. We did it with three guys. Before I went, everyone told me, “You’re mad. You’ll get kidnapped and murdered.” But, the reality, for me, wasn’t like that. I’m not saying all that stuff doesn’t exist, but we were led to a beautiful experience. It’s impossible to get permission to shoot anywhere. The bureaucracy is second only to India, I think. You really have to try hard if you want to shoot in that park. As soon as you get your camera out, someone will come and go, “No, no, you can’t. Where’s your permit?”

Lynn Fainchtein: Nah, it wasn’t so bad.

Bridgeman: Yes, obviously we did it.

There’s obviously a musical narrative and the music propels the movie, but you also use a lot of contradictions to tell the story, such as life vs. death, spiritualism vs. religion, etc. Can you talk about that?

Bridgeman: What happened is, I make movies because that’s the format that has an outlet. But actually, I make short films. The film is twelve short films, and each has a contradiction, a beginning, a middle, and an end. The contradiction usually comes at the end, and in my ideal world, that would end there and then you’d be left. In my first film, 1 Giant Leap, what we did was, there wasn’t even a button you could hit on the DVD that played them all. You’d watch one chapter, and when it had finished, it would come back to the menu, and you’d see “Death,” “Inspiration,” and big, big subjects. So, each film has a little flow. The difficult thing is obviously keeping people in their seats for an hour and a half and keeping them entertained when it’s a non-linear form with no real story and no real stars. I work on the principle that I’ve got somewhere between a minute and a half and two minutes before something has to happen, otherwise I’ve lost my audience. Therefore, in 90 minutes, you’ve got 45 two-minute scenes, and if you look at the film, that’s kind of what it is. I’m not trying to prove anything. I’m just trying to entertain, inspire, and maybe make people think a little bit about something that has happened to them, like “Oh, that’s just like me.” And then, you have this emotional response.

The film seems to have a much quicker pace at the beginning and then things flow a little more slowly towards the end. Can you talk about the editing?

Bridgeman: Maybe you got used to it, because it is a strange format that I’m working in. I have a problem with the end. There’s a director’s cut on the DVD which has a different beginning and a different ending that I think makes it easier, because I find the [current] ending is a bit bitty. There are three or four little bits which make you feel that it’s too long. It is a really difficult form. As I say, it’s non-linear. It’s not like I’ve got a story and suspense or any drama. There’s no drama in it. But how can you make a film without drama?

Television is a huge part of Mexican culture. In one section, the film talks about TV and the perception that some people are ignorant because all they watch is TV, but then on the film’s credits I see Media Azcárraga Televisa. Can you talk about that contradiction?

Fainchtein: Emilio Azcárraga is part of that reflection that something needs to be changed. By changing it within, I think then we make something happen. For me, it is really relevant that they did support this film because it means that something is happening. They’re opening up, and I think that is great. In some ways, that’s what Mexico needs, because also by being on the other side, that nothing is good there, and even if they change to nothing will be good because they are already evil, we can change something in there. If we can put all the content on their screens in Mexico, I think we did something good, because I’m really concerned about that. Monopolies in Mexico are not good, and I think as we can break them, it will be great. If they support a film like this that an audience likes, then maybe we can have more things on screen instead of Telenovelas that people might like. By having Daniel Jiménez Cacho talking about it -- we didn’t hire an actor and give him a script -- it’s his opinion about things. So, Daniel is a spokesperson for things he thinks and that I also share. But it’s also important that there is an actor like Daniel saying something like that because it’s a commitment for him. Having those two sides (points of view) on film speaks about the content of the film as well.

Bridgeman: It’s a pretty accurate reflection of what’s happening in Mexico, because if you’re working in film or television or music in Mexico, you are working for Televisa.

Fainchtein: Nobody puts that in the credits, but we put that in our credits. Do you know how many films are being done in Mexico thanks for the 226 law which is supported by Televisa? (She is referring to Article 226 from the Mexican income tax law which provides a tax benefit to private companies or individuals that are interested in redirecting part of their tax liability to the production of Mexican cinema.) Almost 80% of the films done in Mexico are distributed by VideoCine, so in some way they’re supporting this. I don’t see anyone being supported by Television Azteca. I don’t see Carlos Slim supporting this. There are others. We have the richest man in the world in Mexico and nobody is saying anything. This can be a really long conversation from that standpoint, and I think it’s good that you ask.

Bridgeman: And just to add, they didn’t intrude at all. We had our own crew. There wasn’t a Televisa crew. I had it in my contract that they couldn’t say anything until I gave them the first cut, and they honored that in a beautiful way. Bernardo (Gómez) thought I was going to make a film. None of us realized how mainstream the film was going to come out, and I think that’s great for Emilio (Azcárraga) and Bernardo and really great for us as well.

We often hear that everybody hates Televisa but they still watch Televisa?

Bridgeman: As I was saying, all the musicians, if they want to play, they’ve got to… well, that’s a big subject. Again, it’s a nice bit of paradox for the film.

Fainchtein: It’s another contradiction.

Bridgeman: Yes, another contradiction. Basically, it is a hippie film. It talks about peace and love and surrender and honors the ancient traditions and all that, and it’s sponsored by Emilio Azcárraga.

Fainchtein: It’s a great invitation to do a project. So there must be somebody there with an intelligent mind saying “Let’s support a film like this.”

Bridgeman: Yes. Bernardo Gómez. It was his idea.

This film reveals the beauty and cultural diversity of Mexico that’s not making the news these days. Why would non-Mexicans go to see it?

Bridgeman: Well, several reasons. One, it’s not necessarily about Mexico. It is about music and philosophy and ideas. But, beyond that, because the preconceptions of Mexico are so stereotyped and PR-bad-news-ridden, I think that if people hear there’s this joyous sound coming from Mexico, they’ll be intrigued. I mean, I’ve shown it in England. We premiered it in England, and I’ve shown it to a few friends here already, and it is some big story going on in Mexico. That’s why I’m saying, as a filmmaker, it was such a gift. I don’t know what the story is, and we could talk about that for ages, but there is a big story with the 2012 phenomenon (referring to a global cataclysmic event that will supposedly mark the end of the world) and all the evil, and now, hopefully, we’ve shown all this light as well.

Fainchtein: And Peña Nieto (Mexico’s President-Elect Enrique Peña Nieto) will take office on the first of December.

You have some very well-known musical artists that participate in the film, such as Alejandro Fernández, Gloria Trevi, and Kinky, and then there are others who are virtually unknown, such as the man with the Calavera Mask performing in the city square.

Fainchtein: He’s American. We found him in the streets of Veracruz playing like that. It was our first trip.

Bridgeman: The thing is, we didn’t choose the musicians because they were famous, and that’s why I didn’t put their names on the screen. It’s a basic documentary rule, but I think it doesn’t matter. You either like it or you don’t. That person speaks to you or he doesn’t speak to you.

Fainchtein: Duncan didn’t know anyone really. For him, Alejandro Fernández is the same as the guy in the corner to start with, so his choice was from the music standpoint.

I wasn’t familiar with all of the artists in this movie and I wanted to know who they were, but they were not identified when they first appeared on screen.

Bridgeman: That’s why at the end you get a really nice montage where you see, “Oh! That’s that person. Oh, that’s Gloria Trevi.” Also, the soundtrack I think will be the thing that lasts. The soundtrack is really good. It could be in your car for years. And then, you’ll know which artist it is. It’s Mona Blanco or Moo, and you’ll go online. That’s the world we’re in now, so you don’t necessarily need it instantaneously. I like the challenge, because some people get really angry with me when I sit and watch the film. Like my last film, I sit by someone and they go, “Who’s that?” and I just sit there and I don’t say anything.

It’s called Hecho en Mexico, but then you use artists that are not Mexican, such René from Calle 13 and the Chilean duo. What was the idea behind that?

Fainchtein: They’re friends that appear in the roles that I think had something to say that Duncan was looking for. It’s people that have interesting points of view about different issues and global issues. Suddenly, here’s a guy who’s worried about Syria, and not only Puerto Rico, so he has points of view for this. René was invited as a musician, but also as a thinker, as was Ángeles Mastretta and Adanowsky. We took that liberty.

Bridgeman: But it was still made in Mexico. I’m not Mexican, in case you hadn’t noticed. (Laughs) The title came quite near the end. We had about six working titles. And then, one day, I was talking to my sister and I said, “What do people say when they put the label on ‘Made in Mexico’?” It’s already in the film. There’s a place in the film where it’s sped up and it’s got “Hecho en Mexico.” I thought Hecho en Mexico, and I ran to Lynn and said “What about Hecho en Mexico?” and she said “Sold!” Bernardo and we had had all sorts of discussions, and so suddenly it became Hecho en Mexico. Probably the hardest thing about the whole film was getting the title. For a long time, it was called The Elephant that Thinks It’s a Dog. I even had interviews with people going, “If it’s an elephant that thinks it’s a dog,…?” (Laughs)

You also have some artists who are Mexican but live in L.A., such as radio personality Don Cheto and singer/songwriter Amandititita. Are you challenging the notion of what is Mexican?

Bridgeman: Yes, totally. Is that not Mexico? I’m not sure. As an Englishman, I’ve come to L.A. a lot in the past. And then, I came up from the border with Lynn and my crew through Tijuana, Chula Vista to L.A., and I suddenly realized, “Oh my God, I’m still in Mexico.” I didn’t know that, because when you come here as an Englishman, you don’t think like that.

Fainchtein: It’s a totally different world. When I come to the U.S., it’s a different world than Mexico. From the border to here, it’s two worlds. They smell different, they taste different and they look different.

Bridgeman: It’s still Mexico.

Fainchtein: But this is more organized, clean and proper.

Bridgeman: It’s like Condesa versus Tapalapa. You know what I mean? (laughs)

Fainchtein: Exactly. Not even Condesa anymore.

Bridgeman: What’s the new one? Polanco.

You wrote the movie but wasn’t most of it improvised? How did that work?

Bridgeman: It’s all improvised, but you conduct the improvisation, and then you choose what you like out of that improvisation that makes the point. In a way, the writing comes right at the beginning and right at the end. At the beginning, I was building concepts and ideas that I wanted to explore, and then I explored them and trusted that they would fit. And then, the real job comes wading through all the interviews and going, “That bit and that bit,” and the juxtaposition and the one way it flows. It’s very editorial in a way. Although these are people that are just saying what they feel, imagine each interview was sometimes 40 minutes, sometimes longer, and then I’ll have 15 seconds, so that’s pretty editorial. It’s not that I’m twisting people’s words, but they might say one thing, which is why, like with Don Miguel, I read his book and the bit I loved was, “You are the producer of your own movie, and if you don’t like it, change the star.” It seemed to work really well, so I got him to do that as many times as possible before he started getting irritated with me. We did loads of other stuff as well, but I knew that was the little bit that I wanted.

What has been the reaction to the film in Mexico?

Bridgeman: So far, it’s really odd. It’s a bit scary how in all the reviews that we had in Mexico, there was one. Was it in The Reformer? I can’t remember which paper it was, but it was a whole page, and everyone was going, “Oh my God, you got a whole page and it’s a really bad review.” And it was a really bad review, but in the last paragraph, the reviewer said, “Yeah, but you should go and see it because the music is great.” Everyone seems to love it.

Did you screen the film for all the artists who participated so they could see how their part fit into the movie as a whole?

Bridgeman: Yes. I didn’t do that within the edit, which is where I could’ve said, “I’m not quite sure which bit of you I’m going to use,” but I don’t work like that. I choose what I think is the best thing that they’ve done, and then obviously there was the joy of these artists that night when a lot of people saw it for the first time, and they went, “Oh my God! I’m part of that.”

Fainchtein: But, we showed the film to everybody before we screened it in Mexico. While we were taking all the steps through post-production, there was a period where everybody was invited, and mostly everybody that was involved came and saw the film. We had something like 145 human beings participating in the film.

What was their reaction when they saw the final film?

Fainchtein: As far as I know, they loved it.

Bridgeman: Yes, everybody. Like we said, with Emilio and Bernardo, “You can’t change anything until we give you the first cut,” and we gave them the first cut, and the changes they made were really small. If there’s one word to describe the whole thing, it’s a miracle.