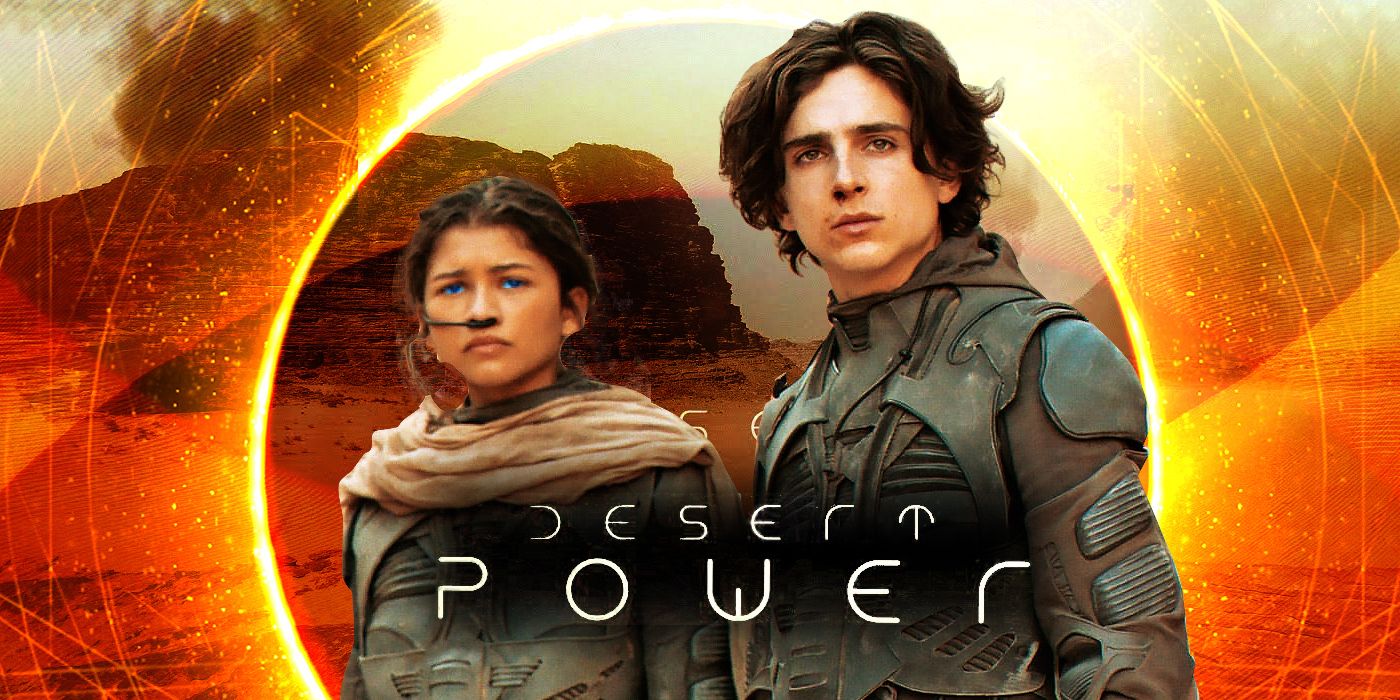

Denis Villeneuve's Dune is a staggeringly large work, a galaxy-spanning Shakespeare-in-space opera that actually does demand the "see it on the biggest screen possible" tag. The only way to take in the scope of this film, with its city-sized spaceships and subway-length sandworms, is to get blasted backward by an IMAX presentation that's still struggling to fit every corner of Frank Herbert's universe into frame. It's grand, it's operatic, it's stunning to look at, and I want to immediately apologize to both Villeneuve and his grand ambitions because the most memorable part of Dune is every single time a character earnestly says the phrase "desert power" like an anime character discovering a new type of Pokémon. It happens at least three times, starting with Oscar Isaac's powerfully-bearded Duke Leto Atreides coining the phrase as a way to describe the untapped political potential of the desert warrior-people known as the Fremen, and ending with Paul Atreides (Timothee Chalamet) coming to the awe-inspiring conclusion that a good portion of harnessing "desert power" means you get to ride a very large worm. Every single time, it brings this impenetrable outer space epic endearingly back down to Earth.

If it sounds like I'm mocking Dune, the honest answer is that I am and also very, very sincerely am not. The "am" portion simply comes from the fact the phrase "desert power" is extremely funny, spoken with maximum gravity in a film that's drier than the Arrakis drifts outside of any scene featuring Jason Momoa's Duncan Idaho. (The second best part of Dune is any time Duncan Idaho arrives in a spaceship to excited applause; this happens twice.) That's by design, of course. Dune is just dry material, a jargon-heavy tale of ancient families making sweeping political moves against each other, far more concerned with the philosophical dangers of religious fanaticism and a forceful clash of cultures than pew-pew firefights. Villeneuve's Dune does feature thrilling, grand-scale set-pieces, but boiled all the way down to its core, it's really just the story of the tumultuous transfer of power at an industrial mining operation. Every time this dense, cold material was interrupted by the words "desert power" felt like hearing a lawyer say "objectamundo" during C-SPAN coverage of small claims court; I thought of Toshiro Mifune bowing his head solemnly in Seven Samurai and whispering "turtle power."

But I'm not really making fun of Dune; I'm meeting Dune on its own terms. I'm definitely not smarter than Denis Villeneuve, clearly a master craftsman in total control of his vision even when it's as unquantifiable as it is on this film. Dune is full of small, incongruous touches that purposely stick out in the year 10,191, from the stuffed bull head hanging in House Atreides that looks like it belongs in a roadside honky-tonk, to the tiny little parasol protecting Thufir Hawat (Stephen McKinley Henderson) from the harsh sun and winds of Arrakis. (The third best part of Dune is Thufir Hawat's tiny little parasol.) These are vital human touches in a story that occasionally feels untouchable, little points of entry that keep the sands from completely shifting beneath the audience's feet. There are just very few opportunities for relatable moments in a story as packed-to-the-gills as Dune. (Too packed for one movie, you may have heard.) So it is essential for audiences to understand that 20,000 years into the future, on a sand-strewn hellscape beyond our current comprehension, a man like Leto Atreides—who is just as much a Dad as he is a Duke—will come up with something as dopey as "desert power." Isaac's delivery, somehow exuding both a cheeky grin and unquestionable confidence, just drives it home.

The jury is still out on the second half of Villeneuve's Dune becoming a reality. But I'd argue Part One ends on, if not a satisfying beat then a complete one; even if we never see Paul Atreides molded into Space Jesus by the Arakkis wasteland, we've seen him accept the role he aimed to reject at the beginning of the film. As leader. As Messiah. As a prophecied figure so cosmically incomprehensible it can only be comprehended by the human mind by breaking it down into the doofiest terms possible. Desert power.