Film franchises are unquestionably the name of the game today. Whether its Marvel, DC, Star Wars, Mission: Impossible, or just a sequel to a movie that came out thirty years ago, getting a movie greenlit without the benefit of it being part of a larger series proves to be rather difficult. Of course, franchises do have the ability for unique storytelling opporunities, where their serialization is not beholden to the structures of television and can generally be played out on a larger scale. On the flipside, many filmmakers choose the path of film, as opposed to television, because they want to create stories around specific instances and themes that don't require thirty hours to tell. Serialized storytelling for these types of filmmakers may feel more confining instead of natural progessions of their work.

However, many filmmakers like to return again and again to stories expressing similar themes. Plenty of directors with the auteur label are accused of making the same film repeatedly throughout their career, from Martin Scorsese to Wes Anderson. What this line of thinking misunderstands is certain people are preoccupied with certain ideas, sensibilities, and questions that constantly run through their minds, and as they evolve as a director, their relationship to these things evolves with them. In order to get movies made, filmmakers with thematic preoccupations either need to find a way to graft their ideas onto a preexisting property or else struggle to get made a standalone film. Alternatively, there is a little explored middle ground between the brand name franchise and the artistically minded auteur that could benefit the craving for both parties, and that is the film cycle.

A film cycle is a series of films that do not follow the same characters with an overarching, serialized story. Rather, they are films linked by thematics, exploring different facets of the similar subject matters across each film. In a sense, a film cycle is the cinematic equivalent to an anthology television series. Creating stories like this allows filmmakers to tackle the concepts they are interested in with great range and detail, while those looking for marketing hooks and branding opportunities can eventize each film as part of a larger whole.

One of the more recent, high profile examples of the film cycle comes from Edgar Wright with his Three Flavours Cornetto Trilogy, which featured his three collaborations with co-writer and actor Simon Pegg. The Cornetto trilogy did not start as a film cycle with the release of the zombie comedy Shaun of the Dead in 2004. That film simply had a brain freeze joke about the Cornetto ice cream, and in the next film, Hot Fuzz, they decided to implement the ice cream again as just a fun nod to the previous film. By the time Wright and Pegg got to The World's End, the idea of explicitly linking these films together was put into action. In an interview with the Toronto Star, Wright said, "They’re all about the individuals in a collective, they’re all about growing up and they’re all about the dangers of perpetual adolescence. With the knowledge of that, we thought there was a way of making this a very final installment in terms of trying to wrap up some of those arcs once and for all."

Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg may have taken a circuitous path to creating a film cycle, but in retrospect, try thinking about one of those films without the context of the other two. It's a difficult task because the three are in such conversation with one another, not to mention removing the marketing blitz of box sets and bundles where you can buy all three films together as The Cornetto Trilogy. Another backdoor film cycle would be John Carpenter's Apocalypse Trilogy, which consists of the films The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness. Each film centres around apocalyptic scenarios. A good majority of film cycles are ones where either the filmmaker or the audience retroactively creates a series because they have only seen their connections afterwards.

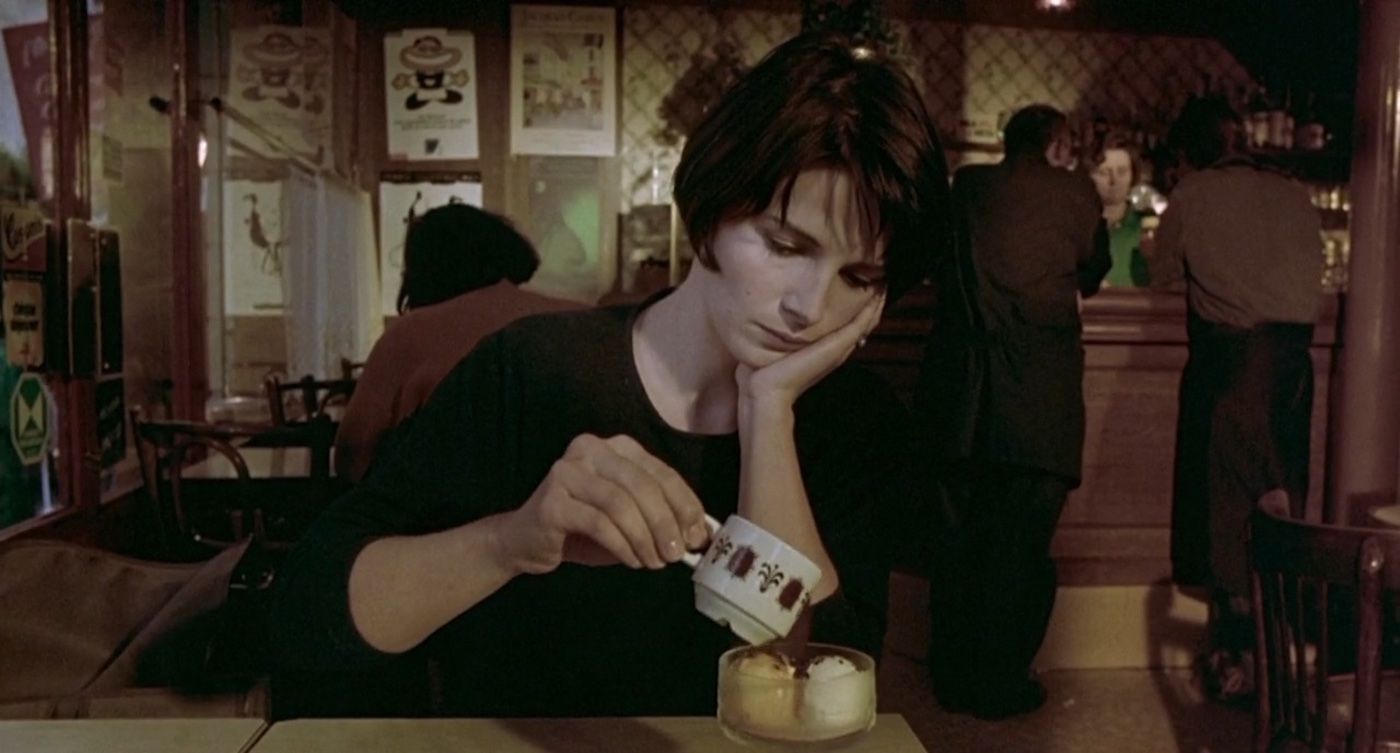

Much rarer, and more tantalizing, are the pre-planned film cycles, and no filmmaker was better at this than Éric Rohmer. The French New Wave master created three film cycles over his six decade long year career, with the six-film Comedies and Proverbs series, the Tales of the Four Seasons, and his first and most famous cycle, the Six Moral Tales. Each of the Moral Tales concerns a man and his relationships with two women. While generally romantic in nature, these are not all love triangles, usually about a dolt of a man, completely in his own head whose not able to understand women and kidding himself about why he finds them desirable. Rohmer wrote four of the six stories as prose before deciding to turn them into film projects. Even in the first film in the cycle, The Bakery Girl of Monceau, Rohmer brands the short film in the opening titles as the first chapter of the Moral Tales series, without any guarantee of being able to finish the series. My Night at Maud's, the third installment, had to delay filming, forcing him to make the fourth film, La Collectionneuse, beforehand, yet he still opens that film with it being the fourth chapter, without the third one having even been made yet.

Having the Six Moral Tales established from its inception as a series deepens each subsequent film with how much further it pushes the cycle's themes. By the time we get to the final film, Love in the Afternoon, not only are we inside the head of Frédéric (Bernard Verley), but his insecurities and philosophies directly echo that of the men at the center of all the previous films, making us feel like we've been following this man for much longer than the runtime of this particular film even though we haven't. Another perfect example of the planned film cycle is the Three Colours trilogy from Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski, where each film corresponds with one of the colors of the French flag and a trait from the motto of the French Republic, "Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity)." The Six Moral Tales and Three Colours trilogy are both hailed as some of the finest film series in history.

These film cycles tend to exist currently in art house spaces, operating as a way for independent and international film fans to indulge in their version of a franchise, because we are in a franchise-dominated film landscape. A current prominent filmmaker taking a chance on their own film cycle on a more commercial scale could serve as a way to give that landscape a needed burst of energy. A mainstream film cycle may have the ability to serve those in the audience hoping for a satisfying, contained film and those who are always geared up for what is next. Not to mention all the marketeers excited to include phrases like "Part Three" or "The Conclusion" on posters and in trailers. Film cycles could be a fascinating compromise found between filmmakers, executives, and audience members to satisfy everyone's cravings in a world anxious about the future of art and commerce coexisting in cinema. It would at least make for a neat experiement, regardless.