Earlier this summer, Collider favorite Edgar Wright posted a list of his favorite films from cinematic history. It wasn't a Top 10 or even a Top 100, but a list of 1,000 movies culled from over the last century. You can find the full list compiled by Wright and Sam DiSalle here, which comes with a word of warning from Wright himself:

This is a personal and subjective list of 1000 favourite movies from 100 years of cinema. It’s not a set text or intended as any bible of ‘greatest’ films. I decided to put this together as a fluid list for my own enjoyment, amusement and reference. I hope it’s fun for you to pore over and dive into some of the films you haven’t seen or haven’t heard of.

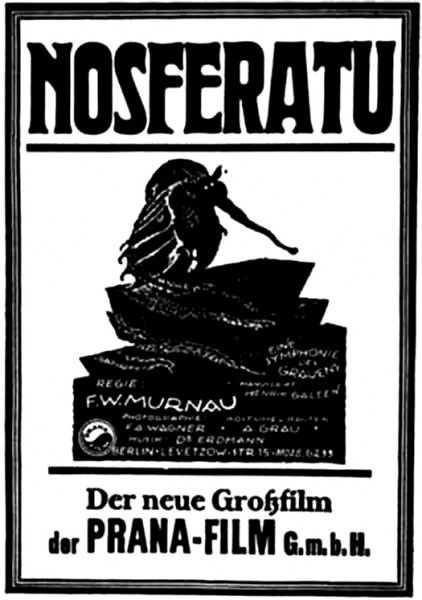

Due in part to some encouragement from Wright's words and to some sort of self-flagellation of our own design, we've decided to revisit each of the films in this list and provide you with a weekly review. If we make it all the way to the end, and if you stick with us, we'll stumble across the finish line together in just over 19 years from now. Like Wright, we'll be tackling the films chronologically. For our second installment, we'll be revisiting F.W. Murnau's 1922 horror classic, Nosferatu.

Last week's revisit of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was an absolute clinic in German Expressionism, a by-the-book example of the cultural movement that favored unnatural and absurd angles, heavily shadowed sets, and an exploration of such concepts as madness and betrayal. Caligari's set design reflected the madness lurking within all of us, perhaps especially within those in a position of authority. This is one area Nosferatu differs quite drastically since its sets are practical, realistic, and so relatively expansive that they make Caligari seem as if it was actually shot within its titular cabinet.

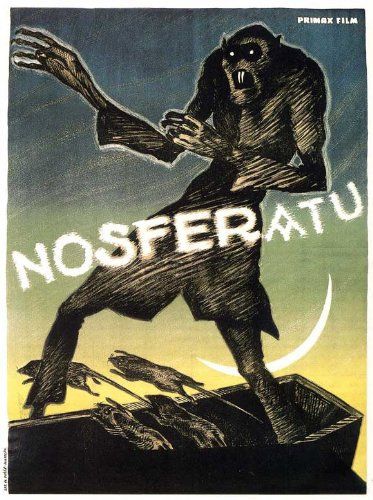

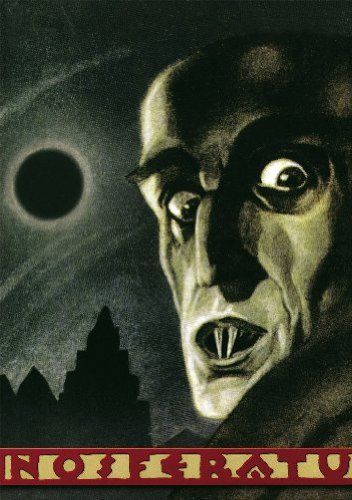

Where the films share some common ground, however, is in their character design. Cesare the Somnambulist is a pale man with sunken eyes and Dr. Caligari is a hunchbacked wild-looking beast of a man at times; Count Orlok (Max Schreck) is somewhat of a combination of these two designs along with some unique aesthetic choices, notably his long, clawed fingers, prominent and very sharp front teeth, and pointed ears. If that sounds relatively bat-like to you, that's because Nosferatu was an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's "Dracula" novel. After a lawsuit from Stoker's estate, copies of Nosferatu were ordered to be destroyed; luckily, some survived, which is more than can be said for the 1920 Soviet film Drakula and Hungarian director Károly Lajthay's 1921 adaptation Dracula's Death, which were both lost to time.

So if you know the story of Dracula, you know the tale of Nosferatu; just swap in the name Nosferatu for vampire, Count Orlok for Count Dracula, Hutter for Johnathan Harker, and Ellen for Mina, and you're 90% of the way there. For the less informed, the crux of the story follows a solicitor (think: real estate agent) named Hutter (Gustav von Wagenheim) who travels from his home in Wisborg to "the land of thieves and phantoms" in the Carpathian Mountains in order to finalize a purchase by the reclusive Count Orlok, leaving his young wife Ellen (Greta Schröder) behind. Along the way, he stops in a small tavern in which local villagers recoil in fear at the name Orlok and warn Hutter that a werewolf is on the prowl (though the animal used to portray said werewolf looks to be a very confused hyena). Hutter's travels soon take him to the nearly vacant and mysterious castle of Orlok, who sleeps by day and has a taste for blood. Assisted by a booklet describing the bizarre and dangerous behavior of the local "Nosferatu" creature, Hutter soon discovers that Count Orlok is more dangerous than he appears. That realization comes too late, however, and an injured Hutter races a shipbound Orlok back to Wisborg in the hopes of preventing the villain from spreading his plague and preying on the innocent Ellen.

Other than the fantastic conclusion, which is one of the best examples of sacrifice and non-traditional storytelling in cinematic history, a few aspects of Nosferatu stood out to me. While there's certainly a heavy emphasis on folklore, local legend, and mythology, there's also a nod toward the scientific side of things. Aside from the doctor who diagnoses Ellen's slow descent toward becoming Nosferatu's thrall as a "mild case of blood congestion," the curious addition of Professor Bulwer (John Gottowt) adds an interesting wrinkle to things. He's studying the Nosferatu legend in addition to other carnivorous creatures, like a Venus fly trap or a Hydra polyp, which he describes as "almost ethereal, little more than a phantom." And while these are obvious parallels to the creature that is Nosferatu, the fact that the movie takes time to show a fly being devoured or the freshwater carnivore in action is a very progressive step for the field of science and science-fiction in cinema.

Relatedly, the origin of the plague that afflicts Wisborg--the sickness that Count Orlok himself brings to the small village--is attempted to be tracked down by the village's officials in a rather forensic manner. They inspect the ship's hold, examine the lone remaining (but very dead) body, and quarantine the village once the dreaded plague is confirmed. It not only works as a terrifying reminder of a pre-antibiotic world, but of a world emerging from the horrors of war in which the relatively nascent concept of germ theory led inexorably to the use of chemical and biological weapons in combat. (This would be be prohibited by the Geneva Protocol a few years later in 1925.)

So while Nosferatu should certainly be remarked as the earliest existing adaptation of Stoker's horror classic, for Murnau's fantastic vision, and for Schreck's enduringly creepy antagonist, its unique place in history allows us to view it at the turning point in the disparate but interconnected worlds of cinema, warfare, and global politics. German Expressionism grew out of a war-forced isolation, but films like Nosferatu continue to reach beyond geographical and temporal boundaries to this day, offering up new perspectives, novel interpretations, and guaranteed thrills and chills. It's a necessary starting point for any self-appointed horror aficionado or cinephile, and a must-watch for even the casual moviegoer.

After two straight German Expressionist horror films, we'll be changing things up with next week's installment, the 1923 silent comedy Safety Last!

Check out the other installments in our ongoing, 19-year odyssey to review all of Edgar Wright's 1,000 Favorite Films: