October is always the perfect month to remember classics of the disturbing and the macabre. And, alongside slashers and haunted house movies, children’s horror is one of the genres most beloved by those who wish to get in the mood for trick-or-treating without leaving their couch. Though spooking children is nothing new, the 1990s was a great era for putting the fear of God (and of witches, and of ghosts) on kids of all ages. From Hocus Pocus to anthology horror series like Goosebumps and Are You Afraid of the Dark?, there was no shortage of supply. Many of these remain Halloween favorites up to this day, earning spots on list after list of what to watch before October 31. Sadly left out of those lists is Eerie, Indiana, a show about life in “the center of weirdness for the entire planet”.

Created by José Rivera and Karl Schaefer, Eerie, Indiana originally aired on NBC from 1991 to 1992. Best known for directing the comedy horror classics Gremlins and Gremlins 2: The New Batch, Joe Dante acted as a creative consultant for the show, as well as a director for five of the series’ 19 episodes, including the pilot, “Foreverware”.

The premise of Eerie, Indiana is a now pretty familiar one: after moving to a small town in the midwestern USA, a young teenage boy begins to encounter strange, unsettling phenomena that he then decides to investigate with the help of a friend. Every piece of evidence gathered is preserved in a locker and duly registered in a secret diary. Some readers might have noticed a few similarities with the plot of the successful Disney animated series Gravity Falls, and they wouldn’t be wrong: in a 2017 tweet, creator Alex Hirsch admitted that Eerie, Indiana was a huge influence on his show about pre-adolescent twins investigating mysteries in a small town in the Pacific Northwest.

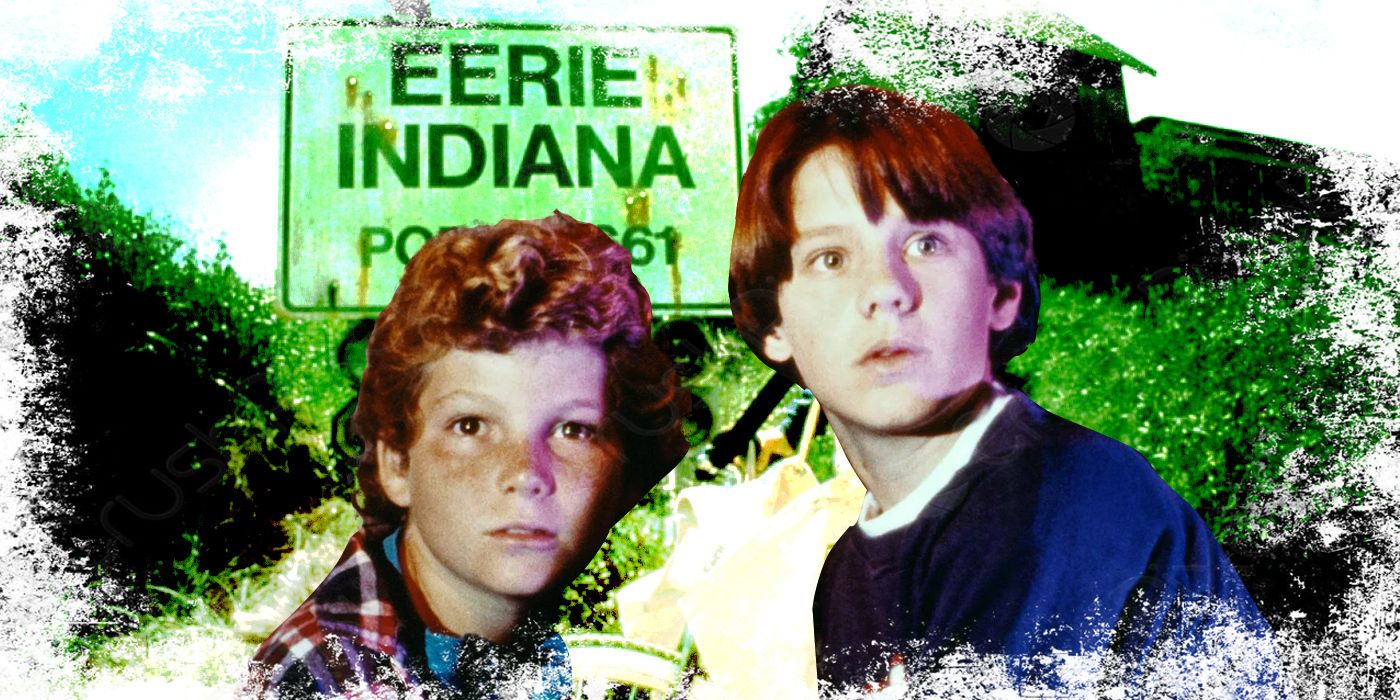

The protagonist of Eerie, Indiana is 13-year-old Marshall Teller, played by a pre-Hocus Pocus Omri Katz. Born and raised in New Jersey, Marshall moves with his father, Edgar (Francis Guinan), his mother, Marilyn (Mary-Margaret Humes), and his older sister, Syndi (Julie Condra), to what is supposed to be the safest, most normal town in the entire country. However, nothing could be farther from the truth. For starters, one of the houses on Marshall’s paper route belongs to none other than Elvis Presley, as alive as he was in 1976. Then there’s the Bigfoot that frequently eats out of the Tellers’ trash can in broad daylight. And those are just the things that happen before the show’s opening credits.

Unlike other horror shows aimed at a younger audience, Eerie, Indiana didn’t rely on jump scares and other elements traditionally scary for children, like urban legends, monsters, and mad scientists. Instead of looking for inspiration in playground horror stories, the show’s writers went for social critique. Apart from the commentary on how moving to a new town can be strange when you are a kid, Eerie, Indiana pokes fun at the cult-like aspects of multi-level marketing, unethical advertisement, and even the arbitrariness of daylight savings time. And perhaps precisely because such topics are so present in the adult world, many of Eerie, Indiana’s episodes are capable of raising a hair or two on the arms of those that were already paying taxes when the show originally aired.

In “Foreverware”, for instance, the Tellers are visited by a woman and her twin sons that look straight out of a 1960s sitcom. Betty Wilson (Louan Gideon) is there for two reasons: to welcome the family to the neighborhood, and to sell Marilyn a Tupperware-like product invented by her deceased husband that can preserve food for well over a decade. But food isn’t the only thing the Foreverware can preserve: before leaving the house, one of the Wilson boys slips Marshall a note that leads him and his friend/assistant Simon (Justin Shenkarow) to discover that Betty has been using the airtight containers to keep herself and her children the same age since 1964. Tired of reliving middle-school over and over again, the boys want out of this immortality scheme they never asked to be a part of. Equally strange, “The Lost Hour” begins with Marshall deciding to protest the state of Indiana’s refusal to observe daylight savings time. His act of rebellion consists of setting his watch back one hour, unlike the other people of Eerie. This results in Marshall being dislocated from the regular timeline and waking up in an alternate dimension. There, he runs into a group of creepy garbagemen dedicated to eliminating things and people that don’t belong in the Lost Hour, like a young girl reported missing a year before, and a mysterious milkman intent on helping the two kids escape.

But the weirdness of Eerie, Indiana isn’t always scary. In “The Dead Letter”, Marshall and Simon open an old letter that was never mailed, releasing a ghost played by a very young Tobey Maguire. Thirteen year old Trip McConnell was on his way to deliver a love letter when he was hit by a car and died. Marshall and Simon are tasked by Trip’s ghost with making sure the letter reaches Mary Carter’s (Herta Ware) hands. Now an old lady, Mary agrees to meet Trip at a local diner, where she dies of old age. In the final moments of the episode, Marshall and Simon see Mary and Trip, now both 13, sitting side by side. It’s a sweet, touching scene that provides children and adults alike with a sincere, but comforting look at death.

The themes of love and death aren’t exclusive to “The Dead Letter.” “Heart on a Chain” dabbles in much of the same topics: after Marshall’s friend Devon (Cory Danziger) dies, his heart goes to the ailing Melanie (Danielle Harris), a girl both boys had a crush on. Nothing exactly creepy happens in the episode, but Melanie’s behavior changes after the surgery and she feels an ache in her chest whenever she tries to kiss Marshall. At the end, Melanie realizes that, though she needs to let Devon go, she’s still not ready to have a relationship with another boy. It’s the kind of story that can only find its way into a children’s show if the writers aren’t afraid of treating their audience as intelligent human beings, and the writers of Eerie, Indiana sure don’t talk down to anyone.

One of the few episodes of the show that relies on urban legend, “The Broken Record” has a father spinning a heavy metal album backwards in search of a reason for his son's erratic behavior, only to have the record play him every insult he ever hurled at the boy. The true horror, Eerie, Indiana says, isn’t the devil and his alleged metalhead followers, but real life emotional abuse.

“The Broken Record”, however, only aired for the first time in 1993, when Eerie, Indiana was being shown in syndication on the Disney Channel. Later, in 1997, the show would also find a new audience on Fox Kids, which prompted the production of a spin-off series called Eerie, Indiana: The Other Dimension. Considered a mere copy of its original, the show was poorly received and, much like Eerie, Indiana itself, lasted for only one season. There was also a series of 17 paperback novels chronicling the adventures of Marshall and Simon.

But with such interesting storylines and so much material to go on, why did Eerie, Indiana never get a second season? The short answer is that he show was a trailblazer, a task that is rarely an easy one. Though children’s horror and TV shows aimed at tweens would bloom in the 1990s, back when Eerie, Indiana first aired, kids aged 9 to 12 weren’t considered a market of their own. There was no time slot dedicated to that age group, and, therefore, Eerie, Indiana was shown on Sunday mornings, alongside sitcoms and cartoons that should be made appropriate for viewers as young as two years old. To make matters worse, the show was frequently scheduled before 8 a.m., a time at which many children aren’t even awake, especially on the weekends.

Schaeffer and Rivera took the task of making a children’s show seriously. In a 1992 interview, Schaefer told the Washington Post that they had a child psychologist review the episodes before they aired so they wouldn’t accidentally traumatize young viewers. However, Eerie, Indiana wasn’t originally intended for kids. Though the basic premise was always examining the world through the eyes of a 13 year old, the series was first envisioned with an adult audience in mind. This explains the numerous references to classic horror that can be spotted throughout the show, from the Invasion of the Body Snatchers' pod being catalogued at the Bureau of Lost to the goldfish Nosferatu to the old Hitchcock Mill.

Caught in a middle spot that wouldn't establish itself until a few years later, Eerie, Indiana took a while to find its audience, and ended up flying under the radar of many that would’ve probably loved it. Currently streaming on Amazon Prime, the show’s an amazing work of weird horror that holds up surprisingly well three decades after its premiere, thanks to the excellent work of both writers and directors, as well as to Katz’s and Shenkarow’s performances. Good child actors aren’t easy to find, and the main duo of Eerie, Indiana can carry even the most disturbing of episodes. The retooling the show underwent in the middle of its single season, with the inclusion of a longer story arc, might seem strange to some, but doesn’t detract from the series’ charm.

Whether you observe daylight savings or not, time certainly has passed since the first episode of Eerie, Indiana made its way into our homes. Now, there are many creepy towns on TV for kids to choose from. But Eerie still deserves a visit. It’s like they say: come for the trash-eating Bigfoot, stay for the beautiful and somewhat unsettling tales about life and death.