The Big Picture

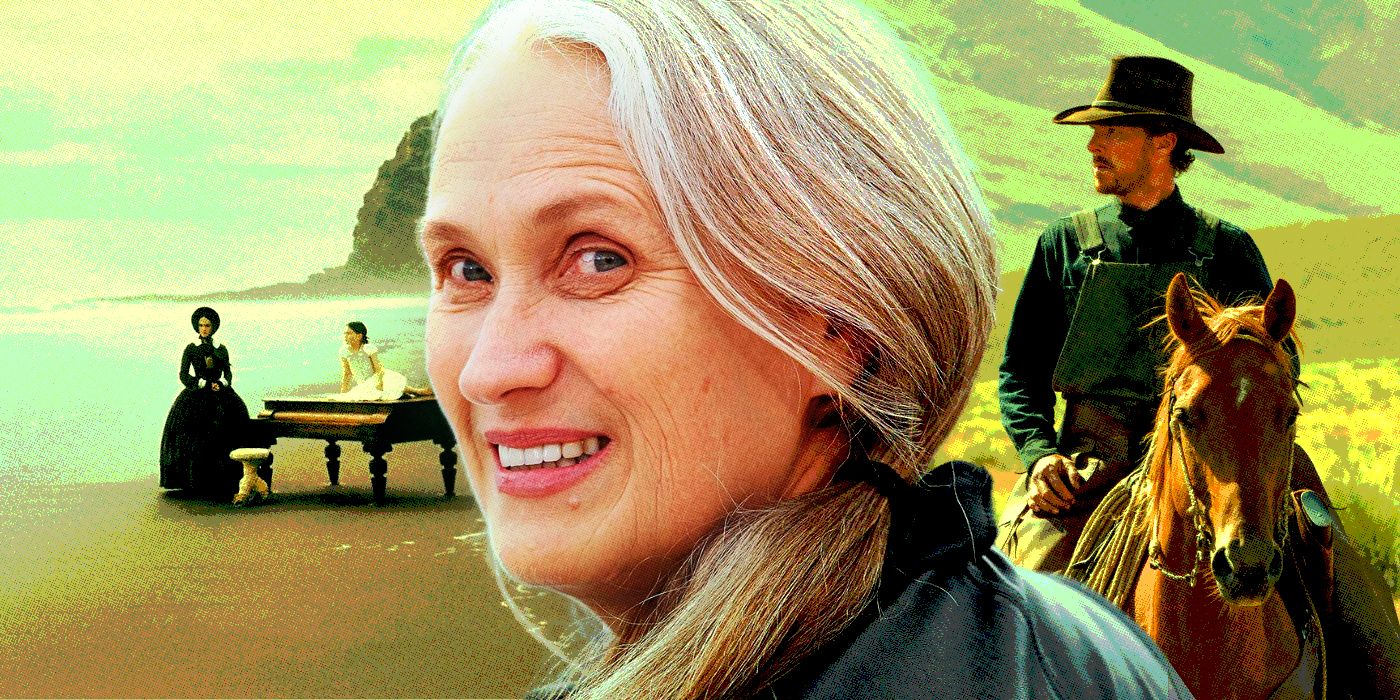

- Jane Campion has made a triumphant comeback to cinema, being recognized as one of the finest living directors, male or female.

- Her films are characterized by sensuality, sexuality, complex women, and fraught family dynamics, but maintain a sense of grace and technical mastery.

- 'The Piano' remains her most acclaimed and successful film, showcasing a perfect blend of sweeping cinematography, beautiful music, and incredible performances.

For a time, it seemed as though Jane Campion wasn’t receiving the respect she deserved. After considerable success in the early '90s, including a critical and commercial smash that won her the Palme D’Or, the New Zealand director released three movies that divided critics and baffled audiences. Had her moment passed? No, thank heavens. After a stint making television with the miniseries Top of the Lake, Campion has returned to cinema in a big way. She’s become the first woman to be nominated for Best Director at the Oscars twice. A new generation of female filmmakers have spoken glowingly of her influence; even her most divisive films have enjoyed critical re-appraisal. Jane Campion is increasingly recognized as not just one of the finest female directors, but one of the finest living directors, period.

There are a number of recurring themes in Campion’s work: sensuality, sexuality, complex women, and fraught family dynamics. Most of all, however, her work is defined by a sort of grace, an ease with itself that’s evident even in her most alienating films. There are a number of shocking, upsetting moments throughout her filmography, but not once does she come across as a base provocateur. Her technical mastery — her unerring gift for composition and atmosphere — holds everything together, providing a beautiful logic for her films to run on. Even the ugly parts feel necessary and true.

Here are all eight of Campion’s feature films, ranked from weakest to strongest.

8. Holy Smoke! (1999)

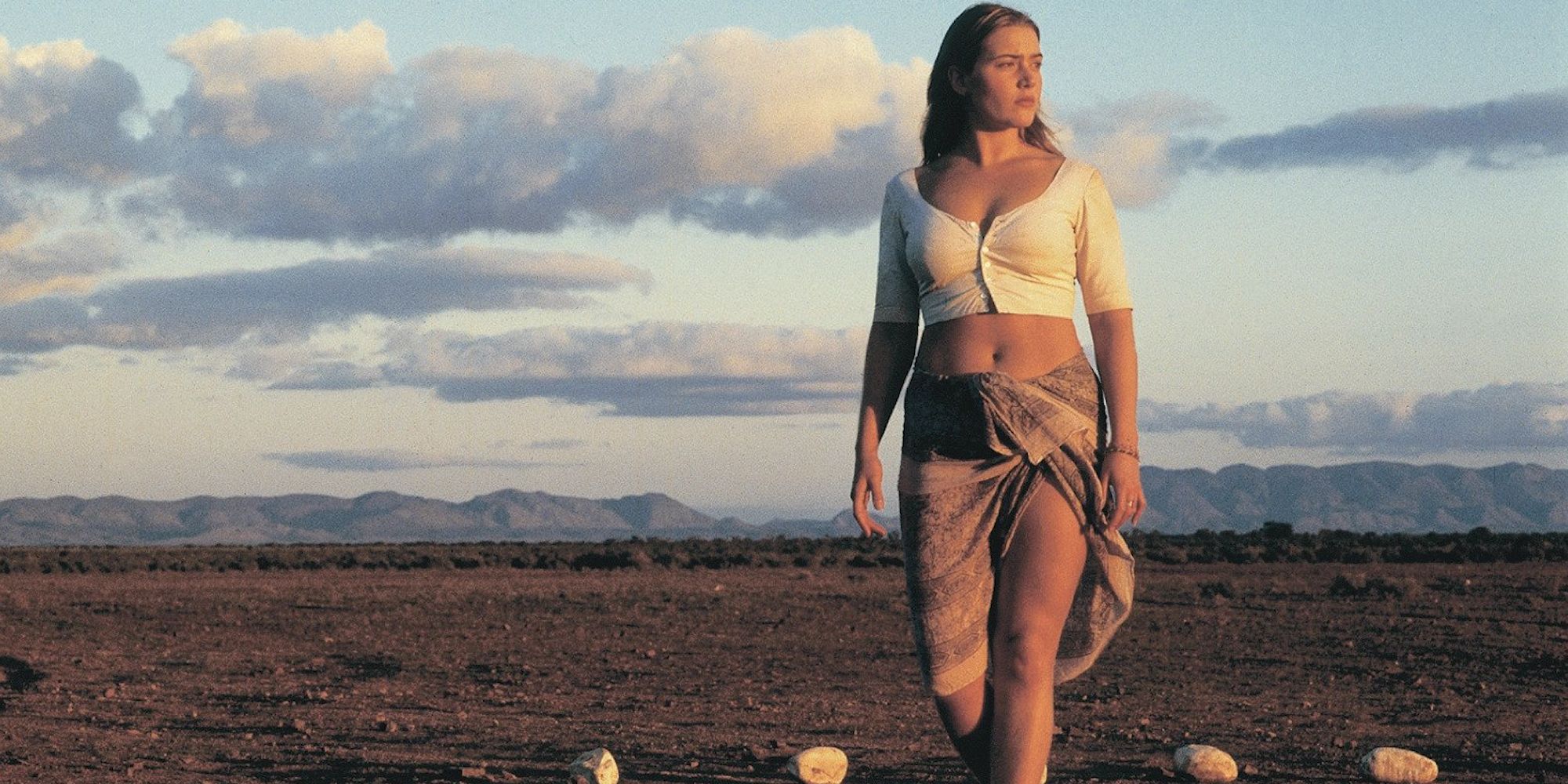

Holy Smoke! has an intriguing premise: Ruth (Kate Winslet) has been swept up in an Indian new-age cult, and her parents stage an intervention with the help of P.J. Waters (Harvey Keitel), a hotshot cult deprogrammer. As the goofy exclamation point in its title suggests, Holy Smoke! is more comedic than Campion’s other work, and it pulls it off surprisingly well. The very idea of a hotshot cult deprogrammer is pretty funny, and even the dramatic scenes have a certain camp sensibility: where else can one see Harvey Keitel in a red dress punch a woman in the face? But the film falters when its cult-deprogramming premise turns into a battle of the sexes that undermines what came before it. As Ruth uses her confidence and intensity to unravel P.J., she seems more likely to start a cult than join one. Still, it’s a unique film, both generally and in Campion’s filmography, and strong performances make it worth a watch.

7. In the Cut (2003)

When a movie gets an “F” grade from audiences surveyed by CinemaScore, it means one of two things: either the movie is genuinely bad (Alone in the Dark, Disaster Movie), or it’s an art movie marketed as something more conventional (Solaris, Bug). In the Cut, Campion’s incisive, feminist take on the psychological thriller, was sold as a movie like Se7en. But while In the Cut also features a hunt for a serial killer in a gritty, noir-ish city, it’s far less conventional than Se7en. The movie is told not from the point of view of Malloy, Mark Ruffalo’s detective, but from his lover Frannie Avery. Played with brittle subtlety by Meg Ryan, Frannie begins to suspect Malloy of the murders. In fact, almost every man she meets becomes a suspect, and she’s not paranoid to think so. In the Cut is occasionally too abstract for its own good, but it succeeds as a lurid thriller that understands women’s terror rather than wallowing in it. Those arguing in bad faith might call it “misandrist,” but Campion’s perspective isn’t one of hatred towards men so much as sympathy for women who never feel truly safe.

6. The Portrait of a Lady (1996)

Coming on the heels of Campion’s greatest success, expectations were high for The Portrait of a Lady. An adaptation of a Henry James novel, it promised to lean into the Gothic elements of its predecessor, and it boasted an excellent cast (Nicole Kidman, John Malkovich, and Barbara Hershey, to name just a few.) But critics and audiences were left cold; the Rotten Tomatoes consensus reads “Beautiful, indulgently heady, and pretentious, The Portrait of a Lady paints Campion’s directorial shortcomings in too bright a light.” But if anything, Portrait highlights her strengths. The production and costume design display her typically sharp attention to detail, with every setting fully realized. She continues to get excellent performances from her cast, especially a nuanced, fascinating turn from Hershey. And while individual plot developments might raise eyebrows (like how Kidman’s Isabel blithely ignores the multitude of red flags Malkovich’s Gilbert sets off), the whole of the eerie, gaslighting experience remains effective. Recommended for those who like their period pieces darker and weirder than most.

5. Bright Star (2009)

Campion had made period pieces before, but never one so understated as Bright Star. There’s no gothic melodrama, and not a single finger gets chopped off. Instead, it tells the true story of the young, doomed poet John Keats (Ben Whishaw) and his romance with the stylish, surprisingly sensitive Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish). As a period romance and a biopic, Bright Star hits familiar story beats, but it’s subtler and more restrained. John and Fanny aren’t constantly gushing about their love for each other, just as the script doesn’t make a fuss over Keats’ genius. The score is lush, but not overwhelming, and many pivotal scenes (such as John and Fanny’s first kiss, as well as the final scene) have no score at all. The film is a treat to look at, thanks to the late Janet Patterson’s artful costumes and gorgeous cinematography from a then-unknown Greig Fraser (Dune, The Batman), but it never feels like a romance novel fantasy. These are real people, with real love for each other, which makes Keats’ death so painful — and the final scene, where Fanny walks through the snow mournfully reciting the titular sonnet, so breathtaking.

4. An Angel at My Table (1990)

An Angel at My Table was Campion’s first trip into the past, which she’s returned to often over her career. By making period pieces, her feminist eye and fascination with power dynamics allow her to explore different facets of history, from the perspective of those who might have been otherwise ignored. Janet Frame (Kerry Fox), the acclaimed writer whose autobiography inspired Angel, wasn’t ignored, but she had to fight to be heard. Shy, depressed, but otherwise sane, Frame was involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital for eight years, where she wrote to keep her wits about her; the day before a scheduled lobotomy, she won a prestigious literary prize, and the procedure was called off. A less curious filmmaker might have only dramatized her time in the asylum, but Campion doesn’t reduce Frame to the worst things that happened to her. Over 30 years and three different actresses, Campion charts her development as a writer and a person: she stubbornly defends her word choices in a grade school poem, she connects with her New Zealand homeland, and she experiences a delayed coming of age. All of this is depicted with Campion’s typical empathy and grace.

3. Sweetie (1989)

There’s something queasily prescient about Sweetie, Campion’s caustic, darkly comic debut. The titular Sweetie (Genevieve Lemon) is a childish, unstable thirty-something with delusions of stardom, whose coddled upbringing turned her into a tyrant. She holds her exhausted, dysfunctional family hostage, demanding constant attention and viciously lashing out when she doesn’t receive it. It must have seemed outsized and grotesque when it first came out; now, the internet is full of Sweeties. Sweeties populate YouTube and TikTok, black holes of drama who are convinced of their own brilliance. For four years, there was even a Sweetie in the White House. Lemon, in brilliant form, embodies the behavior of a malignant narcissist, and Campion nails the soul-sucking cycle of dealing with a person who seems to be pure id. As ruthless as it may seem, however, Sweetie is not heartless: it understands the good intentions behind indulgent parenting, and even finds a bit of sympathy for Sweetie herself. She’s obnoxious at best and terrifying at worst, but in the end she’s just an excitable girl who doesn’t know any better.

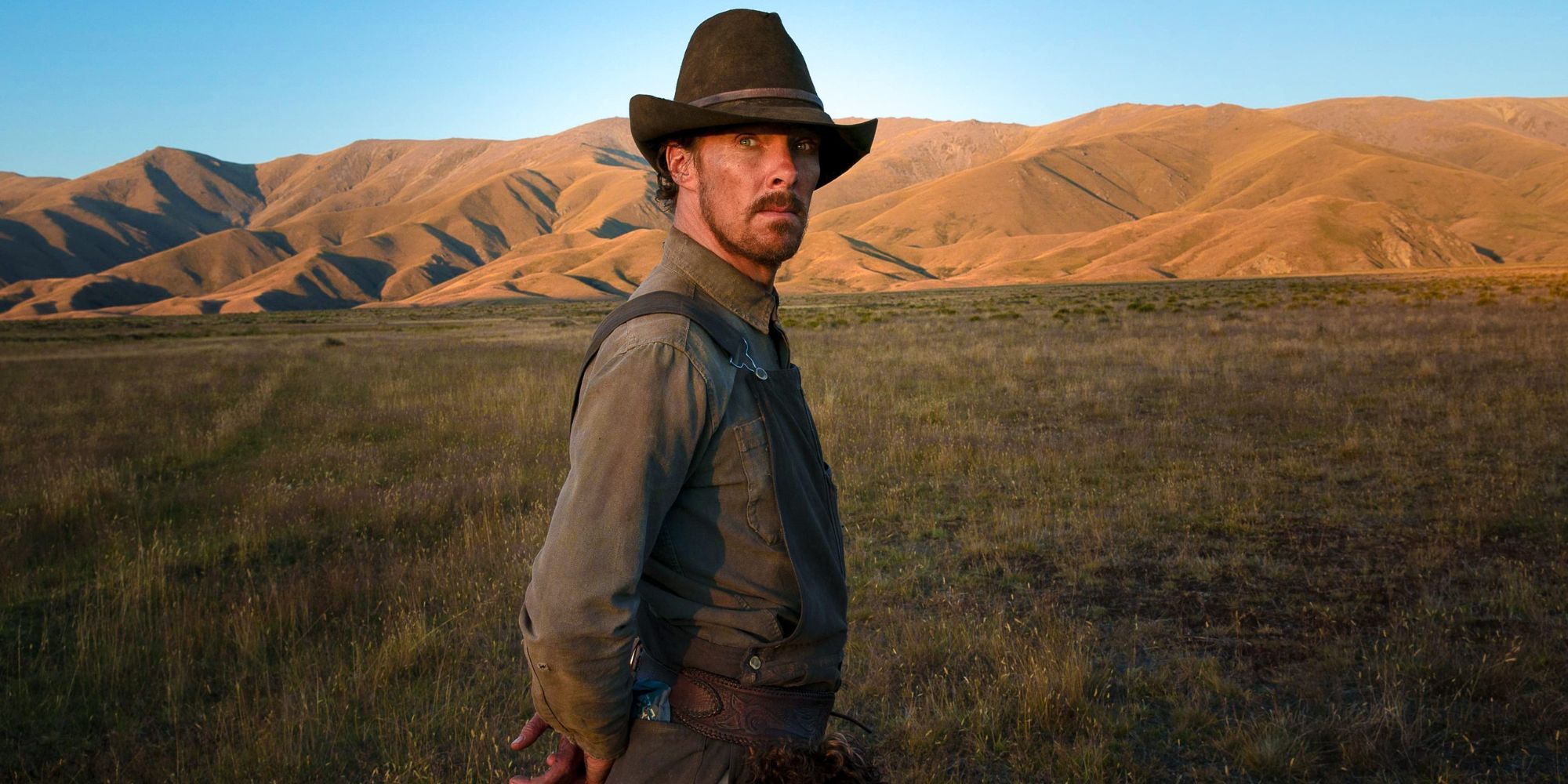

2. The Power of the Dog (2021)

Almost 10 years to the day after her last film premiered at Cannes, Jane Campion’s return to the movies was announced. Two years later, The Power of the Dog premiered to critical raves, racking up countless awards and reinforcing Campion’s reputation as a master filmmaker. It’s worth the hype: Power has been described as Campion’s “victory lap,” but there’s nothing easy or complacent about it. A character drama set on a Montana ranch at the tail end of the Old West, Power shows that neither her visual style nor her writing talents have diminished. Adapted from the Thomas Savage novel, Campion has penetrating insight into the psychology of these characters. The sadistic rancher Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch) is a self-loathing homosexual, but Campion doesn’t leave it at that: she understands that he’s deeper than a gay-cowboy archetype, so she makes Phil a complicated mess of various insecurities and coping mechanisms. Just as compelling is one of Phil’s favorite targets, Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee), a boy whose initial gentle awkwardness hides something more complex and dangerous. Add in painterly cinematography, a dissonant Jonny Greenwood score, and a poignant supporting performance from Kirsten Dunst, and Power has the makings of a modern classic.

1. The Piano (1993)

It was impossible to follow up The Piano. It made Jane Campion the first woman to ever win the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. It made her only the second woman to be nominated for Best Director at the Oscars. (She could have easily won, too, if Schindler’s List didn’t come out the same year.) She won Best Original Screenplay, Holly Hunter won Best Actress, and 11-year-old Anna Paquin won Best Supporting Actress. It was adored by critics, and grossed over 20 times its budget. To make a film more successful than The Piano would require the kind of artistic compromise Campion had no truck with, so she didn’t bother trying. This approach frustrated critics, but it only made The Piano more special in hindsight.

The Piano tells the story of Ada McGrath (Hunter), a mute Scottish woman who moves to New Zealand with her daughter Flora (Paquin) as part of an arranged marriage. She has no love for her husband Alisdair (Sam Neill), but eventually falls for George Baines (Harvey Keitel), the man to whom Alisdair trades her beloved piano. An arrangement for her to earn the piano back turns into a slow, seductive romance, so convincing and erotic that one can look past the questionable implications of the “deal.” What follows is a story of love, repression, and loneliness.

The Piano could have easily become an overheated melodrama, were it not for the fact that everyone involved did their job perfectly. The sweeping cinematography by Stuart Dryburgh captures a world of color in a craggy, remote setting, and Michael Nyman’s score (one of the most inexplicable snubs in Oscar history) swirls and swoons with elegant beauty. Every performance, even Neill’s villainous Alisdair, contains multitudes; the expressive Hunter and the perfectly intuitive Paquin are the best of them all. And it’s all held together by an exquisite craftswoman with a singular vision.