Ingmar Bergman is one of the most respected names in cinema, which comes with a price. When in The Seventh Seal he had a knight and the embodiment of death play a chess game, he unfortunately crystallized what Americans feared was the nature of “Foreign Films.” They seemed pretentious and humorless, about suffering and existentialism. So it’s understandable if the body of work is approached with some hesitation.

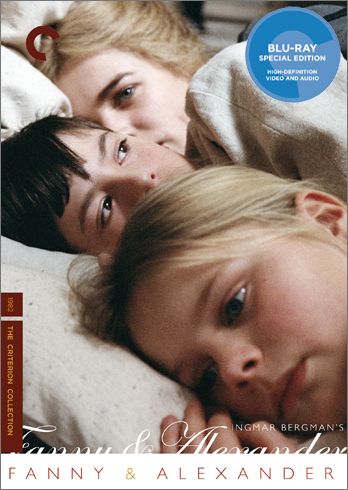

But – though it starts slowly – Fanny and Alexander, his 1982 farewell to directing cinema, begins with a Christmas celebration that features sex and fart jokes. Seriously, jokes plural. Our review of Criterion’s Blu-ray of Fanny and Alexander follows after the jump.

Bertil Guve stars as Alexander Ekdahl, His parents act and run the local theater, and as the film begins they are finishing their Christmas show and going to dinner with the matriarch of their family Helena (Gunn Wallgren). There we meet the family. There are the three brothers: Carl (Börje Ahlstedt) is the broke college teacher always borrowing money from his family; Gustav Adolph (Jarl Kulle) is the more libidinous one – who propositions one of the maids during the dinner, and takes her to bed after; and Oscar (Allan Edwall) is the theater director and father of Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and Alexander, and is married to Emelie (Ewa Fröling).

The opening sets up the family and its loving ways, but tragedy must strike, as predestined by one of Alexander’s dreams. While rehearsing Hamlet, Oscar suffers a heart attack and goes down in front of his son and wife. He comes home and passes away shortly thereafter. Helping console Emile is Bishop Edvard Vergerus (Jan Malmsjö), and a couple of weeks later the two are engaged. Alexander hates him from the start, and when Edvard asks Emelie to take the children to his house without any belongings, the creepy stepfather factor is self-evident.

Bergman said he was inspired by Charles Dickens, and you can see it when the children are basically held hostage by their father-in-law, and forced to go to bed early and basically never leave the house. Emelie sees the mistake she made but finds it impossible to reverse course, and when the children are left alone with Edvard things go horribly wrong. Alexander is strong willed and Edvard’s tough love ways don’t work well on him. From there the movie is about the Ekdahl family’s attempts to get the children and Emelie out of the house.

Set at the turn of the 20th century, what’s always fascinating about watching something like this – Bergman’s five hour last film (though he worked on the stage and TV, and did some screenwriting as well after this) – is how simple and interesting it is. If you want to boil a film like this down, it’s a story of a bad marriage and slobs versus snobs. Because Edvard Vergerus is a preacher, and the troupe of actors are so bohemian, you could argue that the film is anti-religion. Of course it is a long journey and one that takes settling into, but moreso in the five hour cut, which was made for television. Perhaps now that people like Todd Haynes is doing miniseries like Mildred Pierce for HBO there’s a better American template for stuff like this.

Bergman was conscious of the fact that he was saying this was his last film. And so there’s a lot of weight to the proceedings, but not in a bad way – the director puts himself into the work by embracing the theater, and the family that comes from that. Though Bergman showers the Ekdahl’s in warm lights, but it’s Malmsjö’s performance as the priest that’s the standout. You can watch the film and see that everything he believes he’s doing is right, and that he is following his belief system. His actions are never without reason, and that creates a great tension in the material. Perhaps Bergman does want us to view the “villain” of the piece with some sympathy, or perhaps he’s just more skilled at creating villains than the one dimensional characters that normally occupy that role. But it’s hard to render too much sympathy for the priest when the film comes alive any time Gustav Adolph comes on screen, and the film seems to suggest there’s nothing wrong with his sexual arrangement with his understanding wife. Those that embrace their unconscious desires may have a little heart trouble, but are relatively happy.

Criterion’s Blu-ray release is a three disc affair with two versions of the movie. On the first disc is the 321 minute cut of the film, which is presented in widescreen (1.66:1) and in uncompressed monaural sound. On disc two there’s the theatrical cut, which runs 189 minutes, and is also in widescreen (1.66:1) and in uncompressed monaural. I guess there are reasons to watch both versions, but if you’re buying this set, the five hour cut has more fat on the bones, and it’s – especially when broken up over the four chapters – about the passage of time and the scale that comes with that. Of course, it’s easier to fall for whichever cut you saw first – I know I prefer the theatrical cut of Bergman’s Scenes From a Marriage, but I also saw that one first. The second disc also features a commentary by Peter Cowie and the film’s theatrical trailer. It’s a great commentary track and Cowie mixes in anecdotes from being on set, with the film’s production history, and a sense of Bergman as a filmmaker with what he’s doing on screen.

Disc three kicks off with a making of from the period, so it runs feature length (110 min.). And if you’ve ever wanted to see Bergman direct or see Berman work with his legendary cinematographer Sven Nykvist, it’s a treat. They try to make a compelling narrative out of the footage as well, which is a plus. “A Bergman Tapestry” (39 min.) was done for the DVD set and it gets the producer Jorn Donner, production manager Katinka Farago, art director Anna Asp, assistant director Peter Schildt, and actors Pernilla August, Ewa Froling, Bertil Guve and Erland Josephson to talk about the film. It’s great. Then there’s “Ingmar Bergman Says Goodbye to Film” (59 min.), which gets Bergman in 1984 to talk about his decision. The disc concludes with three still galleries.