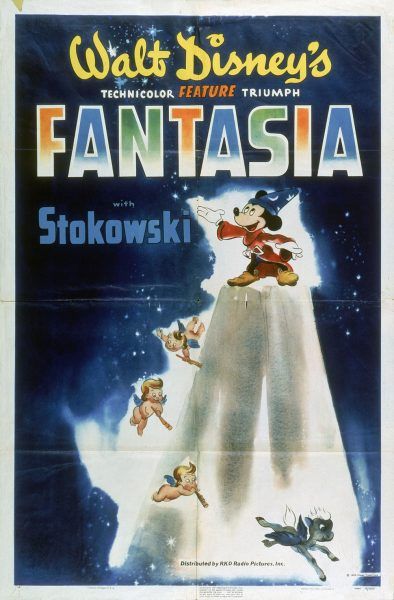

Fantasia was always meant to be a series of films.

According to Neal Gabler’s biography Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, he notes that as early as May 1940, Walt began thinking of a follow-up to his groundbreaking animated feature: he wanted to do an entirely separate movie (with pieces set to Richard Struass’s Till Eulenspiegel, Brahms’s First Symphony, and Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue) but also had the idea of adding new sequences to re-releases of the original film, “which had the advantages of being easier to do and of providing ongoing work for the animators when they needed it.” This was an ambitious plan and one that Walt planned to see through. He told the Hollywood Citizen News, “The prospective patron will consult a program in advance and determine his time of attendance at Fantasia on the basis of his preference in musical numbers and motion picture characters.” Walt said that the film might “vary from theater to theater, from week to week, day to day,” according to Gabler. There was talk of doing one new Fantasia follow-up every year.

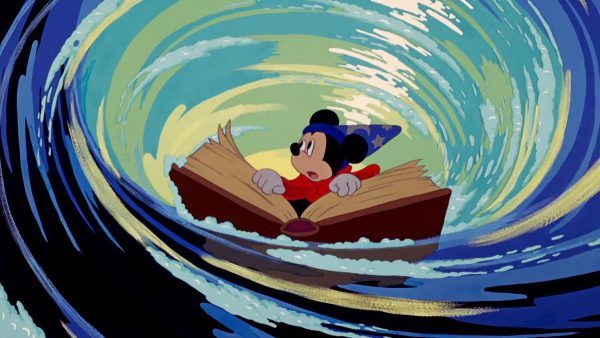

Following Fantasia’s splashy New York debut in 1940, which in its opening weeks required the theater to add eight telephone operators to handle the calls and an adjoining store for the walk-up sales, Walt immediately began work on the sequel, instructing animators to begin conceptualizing pieces based on Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” and Sergei Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf.” The problem was, of course, money. Walt already knew that the purse strings would have to be tighter this time around, floating the idea of only partially animating some sequences and recycling moments from the original film (the dancing mushroom animation from the “Nutcracker” segment would have been repurposed for a new sequence based on Tchiakovsky’s “Humoresque”) – and this was before the financial reality of Fantasia set in, much of it exacerbated by Walt’s insistence to use a proprietary sound system, dubbed Fantasound, that would isolate different instruments in separate speakers. Fantasound was proving to be prohibitively expensive to actually implement.

Before the end of the movie’s initial Roadshow exhibition, plans for the sequel had been shuttered. They were first deemed “individual specials,” instead of segments that would be reintegrated into the initial film or saved for a follow-up. A despondent Walt told the New York Times, “We’re getting back to straight line stuff, like Donald Duck.” As Gabler says, “It was a sad retreat for a man who had boasted for years about the new horizons that Fantasia would open.”

Some of these proposed additions would eventually be animated in the 1940s, when the studio was too squeezed by World War II to produce actual features, and the idea for a follow-up would gain momentum in the early 1980s. For some reason, this period saw a flurry of Fantasia-related interest – in 1982, the film was re-released with digital sound for the very first time and in 1983 John Culhane’s wonderful Walt Disney’s Fantasia coffee table book was released. Around the same time, the studio started work on a sequel, this time called Musicana and influenced by world music. Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman, one of Walt’s Nine Old Men who was still working at the studio, had begun work on the project that the paper described as “an ambitious concept mixing jazz, classical music, myths, modern art and more, following the old Fantasia format.” But this was in the tumultuous early-1980s days of the company, and shortly before the installation of Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, and Jeffrey Katzenberg, who were concerned about the long-term survival of the animation department and not the resuscitation of some decades-old dream.

Indeed, the project was so dead that by 1995 Disney had released an official book called The Disney That Never Was: The Stories and Art of Five Decades of Unproduced Animation that included detailed information about the segments planned for Musicana, most notably an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Nightingale” with Mickey Mouse as the nightingale’s owner. (This was ultimately canceled in favor of the very wonderful Mickey’s Christmas Carol.)

But the Fantasia 2 idea remained a passion project for Walt’s nephew, Roy O. Disney. According to James B. Stewart’s Disney War, Eisner met with Leonard Bernstein about the project but was “cool to the idea.” According to Stewart, “Katzenberg hated it.” Eventually the two came to an agreement: Roy would sign off on Eisner’s plan to release the original Fantasia on home video in 1991, with some of the profits then being funneled into a sequel supervised by Roy. When the videotape sold 15 million copies, Eisner “called Lillian, Walt’s widow, to tell her that Fantasia had finally earned a profit.” Roy started developing the project, now an entirely separate concept than what had been worked on a decade before, and bypassed Katzenberg (who showed no interest, even though he was overseeing the animation department), reporting directly to Eisner.

In the late 1990s, with the luster of the so-called Disney Renaissance starting to fade amidst skyrocketing production costs and lackluster profits (not to mention the added pressure from start-up competitor DreamWorks Animation, led by Katzenberg), the Disney animation slate was scaled back and wayward animators assigned work on what was now being referred to as Fantasia 2000. Stewart describes the development process as being “painstakingly slow,” due to the research associated with combing through archives of classical music. While Eisner had previously met with Bernstein (he’d pitched the composer a segment set to the Beatles), Roy had recruited James Levine, from the Metropolitan Opera, as the film’s music advisor. Eisner suggested a segment set to Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” after attending his son Eric’s high school graduation, with all of the classic characters marching in wedding procession “carrying their future babies” (according to Gabler). Roy and the animators hated it. Eisner’s idea was scrapped but “Pomp and Circumstance” remained.

In the lead-up to Fantasia 2000’s release, Eisner publicly described it as “a remarkable continuation of a completely distinct Disney legacy.” It premiered at Carnegie Hall in December 1999, with the Philharmonia Orchestra of London performing live to picture. (The event cost more than $1 million.) It premiered in 54 IMAX theaters on New Year’s Day and pulled in less than $3 million. Like the original, Fantasia 2000 got middling reviews (Stephen Holden in the New York Times said it “has the feel of a giant corporate promotion whose stars are there simply to hawk the company’s wares”). According to Stewart, Eisner said the film was “Roy’s folly,” and it had convinced him “that Roy had little, if any, talent.” This acrimony would sow the seeds for the “Save Disney” campaign just a few years later, when Roy (and his lawyer and board member Stanley Gold) would lead a revolt against Eisner, first in the public and then with the board, which ultimately led to Eisner’s removal. Eisner told Stewart: “All of my ideas disappeared. Bernstein would have made it commercially successful … Fantasia 2000 lost a fortune.” When what was then known as Disney’s California Adventure opened in 2001, there was a backlot-themed food court in the theme park called Hollywood & Dine. On one of the walls was a futuristic mural, with a number of in-jokes based on the studio’s popular movies at the time. Playing at a Skymax theater was Fantasia 2460.

But what Eisner had failed to mention to Stewart that was as early as 2002, even after it had lost a considerable amount of money, work had quietly begun on a third film. Called Fantasia 2006 internally, it built on the momentum of Fantasia 2000 and there were four segments, fully produced and animated, by the time the studio pulled the plug in 2004 (Disney historian Jim Hill wrote at the time: “The cutbacks at Walt Disney Feature Animation -- both funding and staff-wise -- over the past two years had pretty much stopped any serious development of possible new sequences for the third Fantasia film.”) What is really incredible, though, is that all of these segments intended for the third Fantasia eventually saw the light of day, released in drips and drabs over the years following the film’s cancellation. Seeing one of the segments, presented as a stand-alone short film, you probably wouldn’t think that it was supposed to be part of a larger piece, one that seemed to adapt the “global music” concepts of the past.

In 2003 the short film “Destino” was released to much fanfare. A passion project of Roy’s, it was based on a collaboration between Walt Disney and surrealist Salvador Dali. Walt and Dali met following the release of Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound. Dali had provided imagery for the dream sequences, and the two were connected via Jack Warner. David Bossert’s amazing Dali and Disney: Destino – The Artwork and Friendship Behind the Legendary Film charts their relationship and even reproduces correspondence. Dali wrote to Disney early on, “Very dear friend, I think constantly and with enthusiasm of our future collaboration and every day I figure out new ideas.” While the film was never made, interest was always high for this collaboration. In 1969 much of the artwork the two had collaborated on was stolen, with elaborate maneuvers made to reclaim the art. Frank Wells had expressed interest in reviving the project in the late 1980s, but Wells was tragically killed in a helicopter crash in 1994, before he could push the project along. It was revived by Roy around the time of Fantasia 2000 and while it didn’t make that film, it was earmarked for a follow-up.

“Destino” wound up being a true tour-de-force, incorporating elements (and even animation) from the planned original version, alongside brand new, striking imagery that was mostly traditional, hand-drawn animation (it was directed by Dominique Monféry). At that point it had been worked on for almost 60 years and served as a towering creative collaboration between two of the 20th century’s most artistic minds. And given that it was meant to be a part of a future Fantasia project, it was set completely to music by Armando Dominguez (adapted by Michael Starobin), performed by Dora Luz. And you can watch it on Disney+ right now.

Similarly, “Lorenzo” began as an idea by legendary Disney story artist Joe Grant back in 1949. It was inspired by a moment when a cat dove into a fight between Grant’s two poodles. He wondered what would happen if the cat lost its tail. When artwork for the project was uncovered around the same time as “Destino,” it inspired Mike Gabriel, co-director of The Rescuers Down Under and Pocahontas. He worked on the story and set it to tango music under the direction of producer Don Hahn, which works perfectly with the heightened, expressionistically jazzy visuals. It was eventually released in front of the forgettable Kate Hudson romantic comedy Raising Helen and wasn’t commercially available until a Walt Disney Animation Short Films collection was released in 2015. Even now it remains difficult to find (it’s not on Disney+), despite its cultural and historical importance rivaling that of “Destino.”

Later in 2004, “One by One,” directed by Pixote Hunt and co-directed by Bossert, made its debut on the DVD release of The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride (of all things). Based on a piece of music by Lebo M originally intended for The Lion King (it would later be repurposed for the theatrical show), "One by One" feels both classic and modern. The art style is classically Disney but it deals frankly with contemporary themes: it is set in a South African town (possibly a refugee camp) and it shows how the children get inspired by a colorful feather. By the end of the film they’re flying colorful kites high above their town. This one has really been buried; it’s not even in the “extras” section of The Lion King II on Disney+.

At the Annecy International Animation Film Festival in 2006, Disney debuted the last piece of the Fantasia 2006 puzzle – “The Little Matchgirl.” Directed by The Lion King filmmaker Roger Allers and based on the Hans Christian Andersen short story of the same name, it is arguably the saddest thing Disney has ever made (which is really saying something). Set to the third movement of Nocturne from String Quartet No. 2 in D Major by Alexander Borodin, it is absolutely gorgeous and heartbreaking, a true triumph of truncated storytelling and emotional sweep. It has been re-released, somewhat surprisingly, with regularity over the years. It was an extra on a Little Mermaid Platinum Edition DVD and later a Little Mermaid Diamond Edition Blu-ray and it was included in that same Walt Disney Animation Studios Short Films Collection home video release in 2015. (Although I couldn’t find it on Disney+.)

What most don’t know is that Fantasia 3 was still being worked on after Disney bought Pixar and installed John Lasseter at the head of its animation division. Eric Goldberg, the legendary Disney animator who directed the standout installments of Fantasia 2000 (including the Al Hirschfield-inspired take on George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue”), recounted to me that he had pitched so many times on this new Fantasia project that Lasseter joked about calling it “The Goldberg Variations.” And as recently as October of last year, unconfirmed reports suggested there could be a new Fantasia project being plotted for Disney+.

Clearly, the current crop of Disney artists and animators love Fantasia and are dying to return to that world. Look no further than “Zenith,” Jennifer Stratton’s contribution to Walt Disney Animation Studios’ Spark Shorts program (you can watch this one right now on Disney+). “I watched and re-watched Fantasia growing up and I think I was drawn to how the emotion and art flow together in a dance. I carried that with me throughout my life and it influenced a lot of my work. I felt like we hadn’t seen something like that for a while,” Stratton told me right after I watched the short. And she’s right – we haven’t seen something like Fantasia in a while. Walt never wanted Fantasia to be complete and the lack of new installments feels downright tragic. In the immortal words of Rihanna: please don’t stop the music.