Not long after Carl Showalter and Gaear Grimsrud, the pair of violent kidnappers at the center of Joel and Ethan Coen’s Fargo, whom Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare play respectively, DP Roger Deakins’ camera pans down an enormous statue of Paul Bunyan, as Carter Burwell’s eerie score picks up. The statue towers over the sign that welcomes drivers to Brainerd, Minnesota, one of the key cities and towns that are traversed throughout the Coens’ mordantly comedic masterwork. The statue is seen in a number of shots – it’s even brought up in conversation at one point – and considering the film’s critical view on men and masculinity, this symbolic figure of American folklore and manliness becomes as much a totem of the film as the “you betcha,” “oh yah,” lingo.

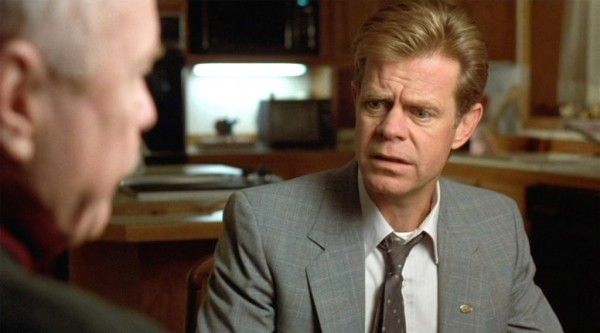

Machismo is something that is severely lacking in the personage of Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy), the bumbling car sales manager that hires Showalter and Grimsrud to kidnap his own wife (Kristin Rudrüd) in the hopes of quietly stealing a sizable portion of the fortune amassed by his condescending father-in-law, Wade Gustafson (Harve Presenell). As written by the Coens, Gustafson is an oversized masculine presence, one of those “self-made men” that certain people like to think of themselves as, whose rudeness, obsession with control, coldness, and greed is all excused by nothing more than their fiscal worth. In contrast, poor Jerry is in the midst of being proven guilty of fraud via a minor scheme at the car dealership that – of course – Wade owns. Here are the two main male archetypes that the Coens see: the rich asshole, and the pathetic middle-class idiot who wants nothing more than to be that asshole.

In comparison, despite their chilling and abrasive demeanors, Showalter and Grimsrud at least have the benefit of being above board in most scenarios. As played by Buscemi, Showalter simply cannot help but say what he means, to unload what’s on his mind, even if he does end up being capable of hiding a large portion of the ransom from his partner. In the world of the Coens, almost everyone’s a criminal, but the people who have chosen it as a career at least have the benefit of experience and their personages reflect the knowledge and, occasionally, the confidence of that particular skill set.

One of the most admirable facets of any Coen Brothers film is the tightness of the narrative, and the percussive editing style that allows them to catch glimpses of moods through movement and stillness, silence and acrimony in between the more plot-driven scenes. One shot that has always stuck with me is the quasi-God’s eye shot of Jerry walking to his car in a snow-covered parking lot following a botched attempt to secure funds for an investment opportunity from Wade. There are planters and lights strategically placed in a pattern-like matter, which both Jerry’s car, and Jerry himself, are out of sync with. It’s not surprising that this sequence ends with Jerry throwing a tantrum, not only due to a not-so-quiet self-loathing but a potent inability to fit in with the wheelers and dealers like Wade, or even his colleagues and acolytes. He’s a man who desperately wants to fit in with the higher-ups but he doesn’t have the instincts or intellect that those people have either inherited or earned over the years.

It’s this attitude that puts him at such a stark contrast with Marge Gunderson, played with a sly intelligence and sensitivity by Frances McDormand, Joel Coen’s off-screen partner. She’s a sensible woman in a traditionally masculine position, the sheriff in Brainerd, but the Coens never suggest that there’s any sort of disrespect shown Marge due to her relative place of power in the police. It’s a curious absence that can ultimately be chalked up to the unwavering professionalism that Marge shows, her self-assured nature that keeps her from boasting but never allows her to cower down when she knows she’s right and someone else is wrong. It doesn’t take more than a minute of screen time dedicated to her on the job to realize how she got where she is and why all her colleagues have such an easy repartee with her, and that’s thanks as much to the Coens’ writing as it does to McDormand’s brilliant, acute performance.

Beyond her obvious skills as a policewoman, she also has a keen understanding of people, and iron-clad common sense, that keeps her from being fooled. When she sits down for drinks with an old classmate, Mike Yanagita (Steve Park), she’s friendly but almost immediately picks up on a clingy loneliness in him, a desperate need for physical contact and emotional connection that she’s neither interested in or available to give to him. (Park’s performance is one of the myriad minor delights of Fargo, so perfectly measured in tone and yet capable of hitting small, unexpected notes of pride, joy, and fear.) So, when she comes in contact with Jerry in two separate scenes, she can similarly see something off in his character, a need to avert attention and play down any sense of mistakes hiding calculated decisions.

That Jerry ends up primarily being in contact with the brash, angry Carl, another man who feels he’s owed a debt from the world around him, and Marge ends up having her final moment of the crime spree with Gaear is at once odd and perfectly fitting. Carl’s fury, his general dislike for people, puts him at odds with the world in a similar way that Jerry is. They both know that crime is what pays, but Carl knows crime intimately and is comfortable with the bloodshed, death, and chaos that comes with it, whereas Jerry thinks that there’s some order to criminal behavior and that crime can be contained, even carry a certain innocence. Carl is under no such miscomprehensions, but he does have an ego about crime, a belief that his comfort with it has given him a special place in the world. And that’s the attitude that both gets him shot across the face, before he empties his entire pistol into Wade at the drop-off, and finally earns him a date with the wood-chipper.

For all his lack of speaking, Stormare’s character exudes a total understanding of what being a criminal is about: survival. He doesn’t talk with Carl because he doesn’t like Carl, and doesn’t believe in any professional courtesies in the world of crime, though he has some sense of fairness, which Carl sees no need to adhere to. There’s nothing elegant or cordial about a life of crime in the films of the Coens, and Gaear knows this, which is why he’s perfectly fine with killing Jerry’s wife and eating crappy microwave dinners in front of a busted television. The silence he gives to Marge when she finds him is a response to her basic sense of humanism, and though crime is inherently human, a successful life in crime requires a lack of humanity and belief in survival over everything else. Marge is wise and smart but she believes in people; Gaear is similarly seasoned and experienced in his work, but that work comes with an indifference to men.

Well over a decade since I last saw the film, and still couldn’t get over the realization of that stump being forced into the wood chipper, the final scene between Marge and her husband, Norm (the invaluable John Carroll Lynch), stuck with me this time more than any of the darkly humorous notes that color the crime spree. When she arrives home to her bed, Marge is greeted with news that Norm’s painting was chosen to be on a three-cent stamp, but Norm is slightly beleaguered, certain that his prize is lesser than the one awarded to their neighbors, who got a higher-value stamp. The Coens hint at the same inherent weakness in Norm that plagued Jerry and sent him into a fit of desperation, a yearning to be more important and be priced better, monetarily, as a person. Marge knows better, and she quietly quells his disbelief with reasoned advice: people need the three-cent stamp, as it’s a cheap, useful commodity when other stamps go old. In other words, money gets old and hides a personality that is lacking rather than a sense of self-worth that one must work at and cultivate throughout life. It’s the small, fulfilling victories, such as having your painting on a three-cent stamp, that push you forward and lend nuance to your personality, and that ultimately make life worth living.