Riley Stearns' feature debut Faults is a taught and charismatic work, and also the latest film to tackle the subject of cults in a quietly earnest way. Like Paul Thomas Anderson's The Master, and Sean Durkin's Martha Marcy May Marlene, Faults explores the desperation of individuals who seek shelter in fringe sects, but is different in the way it also exposes the desperation of one individual (Ansel Roth, played by Leland Orser) who is trying to help reverse that impulse.

Throughout its 90-minute run, both the darkly comedic Faults and its tightly-wound characters morph into many things. Ansel's introduction finds him calmly -- then petulantly -- demanding a hotel's restaurant honor a voucher for his breakfast, which he also used the night before. He makes a dramatic scene over not wanting to pay the four dollars for it, but the tragic truth is he doesn't have it.

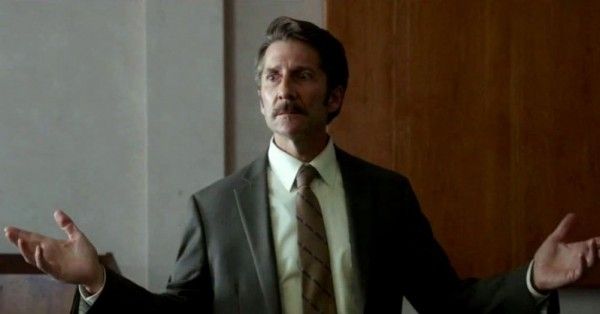

Though he's an author, a former talk show host, and a professional deprogrammer (of those taken in by cults), Ansel has nothing, and commands no respect. He's punched, slapped, beaten up, and suffers from constant nosebleeds, bullied even by those he has hired to help him execute his latest scheme.

After a particularly difficult day, Ansel is approached by an older couple (Beth Grant and Chris Ellis) who try to convince him to help their daughter Claire (played by Stearns' wife and the film's co-producer, Mary Elizabeth Winstead), who has been drawn into a cult called Faults. Ansel at first rebuffs them, but desperate for their money, accepts the task. Just as a payday seems eminent, he's hounded by his former manager Terry's (Jon Gries) hired muscle (Lance Reddick) into paying back the money he owes for self-publishing his latest book. Though Ansel taking on Claire's deprogramming seems driven by the money, he also truly believes it can work, because it has to. It would mean that he is not an abject failure (a previous attempt at deprogramming ended tragically). Claire, though, has strong beliefs to contend with as well.

Faults' setup is simple, but Stearns doesn't need much setup for his concept, since cultural touchstones have already done the legwork. Claire's peasant dresses are evocative of fundamentalist compounds, while Faults itself feels like it has shades of Heaven's Gate and other well-known sects. The smaller details speak volumes as well: Ansel is a familiar kind of self-interested lecturer, and the holes in his undershirt and the bland brownness of his suit speak to his failures. The motel room is similarly retro and drab, livened up only by the seesawing emotions of the film's leads (who are both exceptional).

Much of Faults takes place inside of that motel room where Ansel holds Claire captive for five days in order to convince her to give up the cult and go back to her parents (who are in the adjoining room). Yet Stearns' direction never makes the experience feel claustrophobic, as he uses every corner of the space. Though Faults limits itself some by hiding in the cavalier, and never becoming fully engaging on an emotional level, its tackling of Big Issues is never heavy-handed, and never drags.

Ultimately, as Ansel becomes increasingly desperate (as demands by Claire's parents as well as Terry continue to escalate), Claire becomes a staid voice of comfort and reason. The film's third act feels rushed, and some of its final scenes a little unhinged, but as it wraps up, there are certain aspects to its exploration of identity and control that are both surprising and satisfying. Then again, as Claire suggests, maybe we were led to exactly that place -- we just didn't realize it until it was upon us.

Grade: A-

Faults is currently in theaters.