One of the most exciting cinematic events of this summer was certainly the rollout of the Fear Street trilogy on Netflix. Every Friday, for three Fridays in a row, a brand new Fear Street movie was released, slowly unveiling the story of a group of teens living in a cursed town called Shadyside. Each film took place in a different time period — Part One in 1994, Part Two in 1978, and Part Three in 1666 — and each pulled back the layers of the story, culminating in a third and final film that revealed the true origin of the town’s curse and provided closure to the story that began in Fear Street: Part One.

The whole thing, as directed by Leigh Janiak, was wildly entertaining, and part of the fun was the diverse aesthetic of the trilogy. Each film looked and felt different, pulling from iconic horror genres while also offering up a wholly unique feast of its own, serving the characters and story first and foremost. All three films were shot back-to-back-to-back in the spring and summer of 2019, and the dynamic aesthetics of this herculean effort were brilliantly captured by cinematographer Caleb Heymann.

During a recent exclusive interview with Heymann, the DP told me he was frankly surprised he landed the job as the cinematographer of the Fear Street trilogy. He had primarily worked in the indie film world, and before landing Fear Street was most recently working as a second-unit cinematographer on the third season of Netflix’s Stranger Things (which is co-created and co-run by Janiak’s husband, Ross Duffer). But he and Janiak connected over their shared vision for the trilogy, and Heymann hit the ground running when he reported for duty in Atlanta.

Our wide-ranging interview, which you can read in full below, covers how Heymann pulled from influences like Scream and Terrence Malick for the trilogy, and he broke down how he and Janiak settled on the unique aesthetic for each film that kept the characters top of mind. He also broke down some of the biggest challenges of the shoot, including that disturbing hanging scene in 1666, and how he managed to keep all three films straight in his head while shooting them back to back. Heymann also spoke briefly about his work on Stranger Things Season 4, for which he served as the cinematographer for multiple episodes, and for which he says every episode has “essentially a movie’s worth of material in its own right.”

While Heymann may have been largely unknown before Fear Street, this incredible trilogy proves he’s an exciting young talent in the field of cinematography, and I truly can’t wait to see what he does next. Check out our deep-dive interview about all things Fear Street below.

How did you first get involved in Fear Street?

CALEB HEYMANN: I knew Leigh for a while and I had worked with a couple of her director friends on short films that she had seen. And then I was very lucky in 2018 when Stranger Things Season 3 was being shot to get to come on and do second unit. And of course, her husband Ross directs and is the co-creator of Stranger Things, along with Matt, so in this kind of very odd and synchronistic way, I had worked with a lot of the people that Leigh knew. But mostly on independent projects. Stranger Things was the one exception. But I'd never done a studio project before, so to be honest, I was quite surprised when she approached me and wanted to talk about Fear Street. It seemed like a super long shot.

But I put together the treatment and pitch and we sat down and started talking, and we just really connected on it. We both grew up in the 90s where you hang out at the shopping mall with your friends watching movies like Scream, so I think we both could immediately relate to the setting of Fear Street 1994, but also the desire to do something that was an homage to films of that era that we'd grown up on.

So I think there was something that really clicked for both of us about that. We started talking, and really were both excited about telling this queer love story and this story of outsiders, that even though it was an homage to films of that era, it was about a relationship that couldn't exist openly in that era, and you didn't really have films like this back then to explore that kind of love. So we were both drawn to that and Shadyside being this town of marginalized people. Leigh was talking a lot about wanting to explore these visual echoes with how history repeats itself and how the violence repeats itself. There was both these super interesting themes that I just loved and gravitated toward, but then she also wanted to do it with this tone that was very playful and very fun.

And then of course we went through these visual references that I'd put together. She was scrolling through it on my laptop, and I was just nervously sitting across from her at the cafe wondering what the hell she's going to think, and if I'm completely off base here. And then after kind of a couple of minutes of going through, she's like, "Yeah, yeah. This is awesome." This is exactly the type of thing that she wants Fear Street to become. She told me it was really about kind of trusting somebody's taste, I suppose, to kind of be a co-creator of this world. And the fact that a lot of the references that I was bringing in were very much in line with how she saw it and how production designer, Scott Kuzio, saw it. She just decided to take a chance on me. I mean, really, take a chance on me.

After that meeting, about 10 days later or so, she was already down in Atlanta prepping and I got a call. She said, "Dude, we did it. You're on." And she left with, "Now you better come down here and crush it because I've stuck my neck out for you." So no pressure (laughs). It was very surreal to have the opportunity to work on something as cool as this and as epic in scope as Fear Street.

I was just curious if you could kind of walk me through the process of creating the tone and the aesthetic of each film and making it distinct?

HEYMANN: I think it was important for us to have the trilogy feel cohesive and there were certain things with the camera language that we carried throughout the films. But of course, we wanted each film to also feel distinctive and to really feel of that era in certain ways. So from the very get-go when we had our first conversations, we already had this idea that 1994 was going to really kind of feel in certain ways like films of that era, like Scream. She had the idea that it was going to be dollies, techno cranes, a lot of camera movement, and a pretty fast paced edit and that she deliberately wanted to contrast that with the handheld of 1666 and to completely leave all that technology behind.

So that was a really cool starting place for us. We had to do a lot of pretty methodical prep for 1994, knowing that we were going to have much less prep for 1666 in less time, but saying, "It's going to be okay because we're handheld, and we're going to have this philosophy more like Malick in The New World with lighting entire spaces, and we're giving our actors a lot of freedom to roam.” So it complimented the way that we had to approach the projects practically, as well as being creatively what we wanted.

So that was the starting point. 1994 had to establish the world of Shadyside and so we're kind of figuring out what that wants to be and the tone of it, the colors of it, knowing that we wanted to go really, really dark and have it feel dangerous, and yet still be colorful. Finding that balance, really, between the beauty and the terror and between the laughter and the horror was a really important part of this project that I think appealed to both of us. I remember in one of our first conversations, there was this term that came up, the beautiful decay of the world of Shadyside. And that was something really fun to lean into and being able to say in this town that, for instance, it's very rundown, so streetlights don't work. And I'll take it a step further and say, "Okay, in this school... Well, let's just say they don't have much money for electricity. The overheads are off."

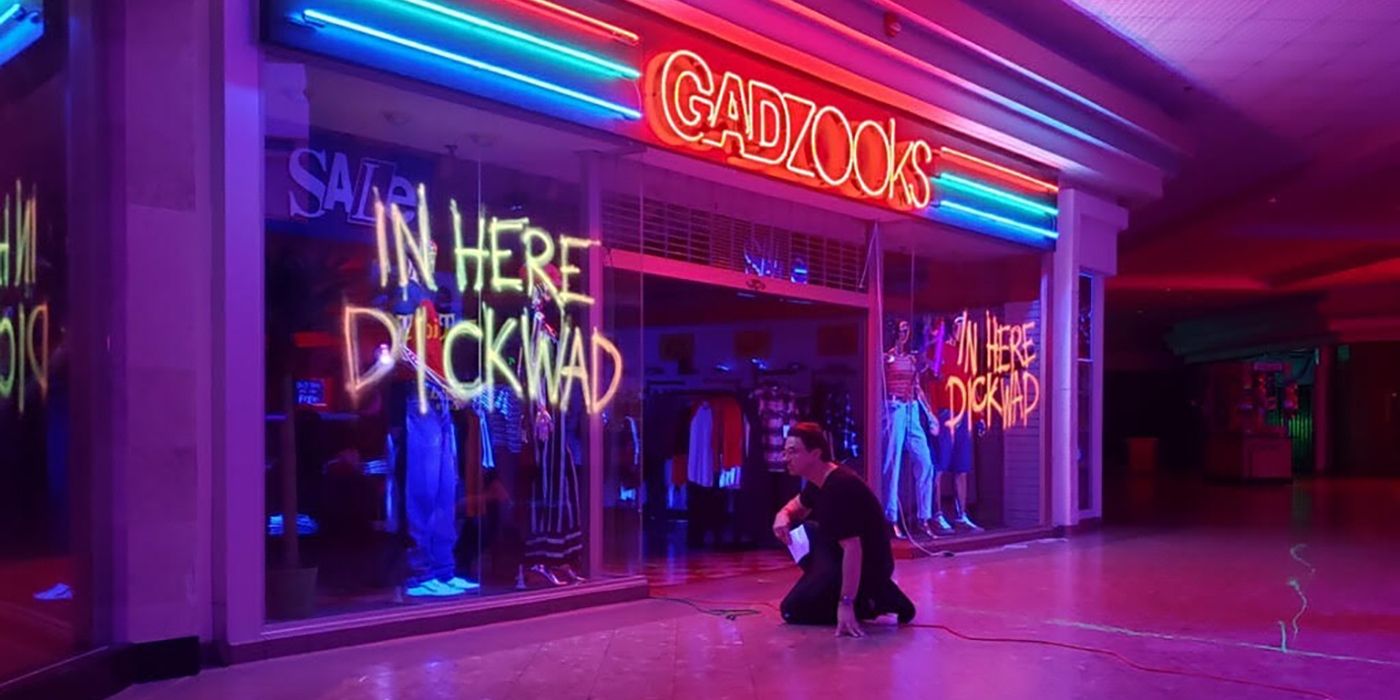

So instead of having this very flatly lit fluorescent environment, you can kind of pocket the daylight coming in through the windows and have areas that get really dark.. So both because of the town and because of Leigh's desire to go super dark, it was a fun place to begin with in 1994 knowing that we were going to be walking this line of being very underexposed and yet wanting to really feel the colors, and wanting to set apart the colors and the tonality from 1994 from the other films. So fortunately in the script you know that you're going to be in a mall with all these neon lights and there's going to be this huge period at the end of Part Three, but in the world of 1994, where it's all UV lit.

So it's all about this crazy artificial lighting, and what was really exciting was knowing that we're going to be juxtaposing that with 1978, where it's a much more simple palette of lighting, but one that I still found beautiful with the tungsten and the cold, uncorrected, greenish fluorescents, and of course, moonlight. And then going back to 1666, where you're just in this raw, elemental, fire, sun, and moon. So it was really just leaning into that and embracing the contrast of the colors while still keeping the tone similar. There weret a lot of things that we knew we wanted to kind of do throughout — - these center punched compositions, occasionally cutting to these omniscient POV's where the camera would move in a more mechanical way, getting used to inhabiting the perspective of the evil itself and our witch’s possession moments.

And then there's other things that weren't as premeditated, but we just sort of discovered on the way, partly because there wasn't a whole lot of time for prep. Doing counter zooms just arose spontaneously when we were shooting Slater in 1978. It was just a matter of saying, "Okay, well, gosh, it feels like we've done about everything by now. We need to do something different for this moment where he's starting to lose it." And we're like, "Hey. Why don't we throw in a zolly and see how it goes?" And it worked so well for that moment that it became a visual motif for us, where anytime there was a killer flashback, we’d use zolly’s to give it this very unsettling feeling.

So you come in with these ideas for a look book and some references for generally how you want things to look, and then they really evolve as you go, based on the actual locations. You get little ideas that you come up with on the day.

You mentioned the echoes and stuff. I mean, it's fantastic when you reveal that the hanging tree is in the mall. And that shot feels evocative of the shot of the hanging tree in '78. There's a lot of that throughout. How difficult was that to keep straight? I mean, I also feel like we're kind of underselling the notion that you guys made three movies, back to back to back, which is not easy. But then also kind of keeping them together. It's not a TV show. These are three feature films.

HEYMANN: (Laughs) Oh, yeah. It was a lot. Certainly too much for me to keep it all in my head at once. So I would rely on spreadsheets, which I think is a useful tool for a cinematographer anyways. But just a little one-line description of what's going on and what you did, whether you were handheld, and just a brief summary of what you're doing there that can allow you to quickly see the arc of a film. That, and stills. Galleries of stills that would then accumulate and I would keep in story order to kind of see how the look of each film was evolving. But no doubt, it was always a challenge. What helped was essentially starting with 1994 and having a long stretch where we shot everything. It was location work for 1994, so of course you're going out of sequence, as far as the films' chronology.

But we did most of 1994: Part Two in that 1994 window. And then we moved on to 1666 and spent several weeks in that world, and then what gets confusing is that then you move on to stage to do the pieces that get built on stage, such as the underground tunnels with all the moss and the wigwam set and stuff that just practically has to get built out onstage. Now you're suddenly jumping back and forth between 1994, 1666, and eventually 1978. And within the same day, sometimes you're shooting pieces of all three and really trying to keep it straight and keep true to what you initially intended to do. I mean, to be honest, so much of that comes from Leigh, who really had spent so much time with the world, with building these worlds, with developing the project, with being in the writers room with the other writers. And even though she was credited for 1994, she was also, of course, writing on all three of them. So just knowing this story so deeply that she could be that sort of check on us was great.

And then, I mean, the nice thing is that by the time we got around to shooting 1978, it was a bit more of a freestyle, because we'd been working together for so long. Even though we weren't initially planning shooting 1978, there was enough trust built up that we were able to very quickly figure out what we wanted to do, come up with a sort of visual style that borrowed from things that we'd done in 1994 and 1666 — because we shot 1978 last — but that also was doing some new things visually. Then we just rolled with it. But it is kind of terrifying working on three films at the same time. It does sometimes make you wish for the simplicity of just being able to focus on one singular feature (laughs).

Was there one particular sequence or scene that was the most challenging for you throughout the shoot?

HEYMANN: Yeah. I mean, there were a number challenging sequences, of course. I mean, with the witches hanging scene in 1666, where Sarah Fier is hung, to a casual viewer it doesn’t seem like there's anything particularly challenging about it. But I think what was challenging about that was it starts off when she's breaking out of a tunnel underground that's leading from the tunnels into the church, kicking through the floorboards, which was the last thing we shot on stage basically. And then cut to above where we're out at the actual village church, even though it's an interior at night. We were busy lighting the scene when a thunderstorm rolled in on us. In Georgia, as long as there's been a lightning strike within six miles, you have to shut down your generators and everybody has to basically stay where they are. So we were just looking at our watches thinking, "We're screwed tonight." Had this plan for hard moonlight coming in through the windows of that church and how I thought I was going to light it and then suddenly all those lights have to come down. The generator switches off. And this wasn't the kind of project where you could say, "All right, well, we're just going to takeour losses on that and wrap early and come back tomorrow. You have to be able to pivot. So fortunately, we had these battery powered lights that had built in batteries and don't require any kind of generator. We were able to hook up an iPad so it could talk to the battery powered lights and all of our normal monitors are gone, but we had a couple of small monitors too that we could run off batteries. And we lit the whole church with that as kind of a hail Mary just to keep on shooting even though it was a bit flatter than I would have liked. These Titan tubes didn’t exist until just a couple years ago and that technology saved us that night.

And then Sarah comes out and is discovered by Solomon on her way out, and then it kind of goes into this pre-dawn sequence that’s the few minutes before the sun breaks. But the challenge of that was that this whole scene is probably five pages of the script that has to take place in the pre-dawn light that includes the hanging and has the whole town gathered around and has the whole march toward the hanging tree.

So a lot of it is just, how do you schedule this stuff to make it work? How much are you able to extend the shooting window before things really fall apart visually and how do you take away enough light? We ended up shooting the scene split between two days beginning about two hours before sunset and shooting until the end of twilight. A couple of the shots we actually had to light at night because we fell a little behind, and that’s being intercut with shots that were done hours before when the sun was still blazing, so as a DP it’s a stressful situation. We were lucky that we had a line of trees next to where we were shooting, so the sun would get behind that about 45 minutes before sunset, so we were able to get some shade and then we bring in a bunch of overheads and big black silks to take away the light off the faces and start with the closeups and work our way out to do the wides last when the light is fading. And then you come back the next day at the same time and you pick it up. It was the one sequence that we split over a couple of days so that we could have it all look like it was this really dark, kind of ominous and blue, pre-dawn light, which was a really cool opportunity to be in this sort of liminal space between night and day

But it's always scary for the cinematographer when you're having to hope that you're going to be able to make it all right in the grade. Fortunately, we had a great colorist in Skip Kimball, who I think matched it all up really well. But you have such a narrow window of time to shoot things, so you have to be methodical about getting the most out of that 90 minute window of light and shooting things out of sequence, even though people watch the scene—

It goes by in a couple of minutes and you guys spent days, right?

HEYMANN: Yeah. Exactly.

I did want to ask you about the final shot, that credit stinger. I know Leigh has said that she would love to do more Fear Street films. I was just curious what went into the conception of that shot? How much to show, how much not to show of who's grabbing the book off the floor and stuff like that?

HEYMANN: Yeah it was fun to end the film returning to our omniscient POV moving methodically from outside into the mall, past the tree, into the underground tunnels and ending up in the pentagram room where the book gets snatched. That very last shot was on a crazy day where I remember it was a Friday where we're shooting on stage and we're spread out through three different parts of the warehouse that we're shooting in, and we shot that while we were shooting another tunnel scene . And it was a real tricky shot to get, because we had to basically thread the needle where the camera had to fit through this tiny hole in the wall on its way to the book by nose mounting the camera on the Technocrane. But I mean, that one was really all Leigh. We knew that we wanted to leave with a bit of a mysterious sting like that, to leave the world open to more evil lurking. And it probably took about twelve takes to get the perfect hand snatch, little things like that end up sometimes being the hardest to get right.

I know you worked on the next season of Stranger Things and I was just curious how that shoot has been for you?

HEYMANN: Yeah. That has been quite an epic adventure. It's basically-

It's been going on for forever.

HEYMANN: (Laughs) Yeah. It started for me shortly after we left Fear Street because I started in January of 2020, and then we were prepping and then we were shut down for five months and we started up again in August of 2020, and then I just finally wrapped last week actually. So, after 11 months of going nonstop on it. And I thought Fear Street was as big as it was going to get (laughs). I thought three movies at the same time was daunting, and suddenly with Stranger Things we find ourselves — every episode is epic in scope and is essentially about a movie's worth of material in its own right. So suddenly we're working on essentially various movies at the same time. It was super crazy, but so incredibly rewarding. I mean, just the amount of hard work and creativity that goes into pulling it off, it was just a massive privilege to be involved in it. And I know the fans are in for a huge treat when this comes out.

The Fear Street trilogy is now streaming on Netflix. Stranger Things Season 4 will be released in 2022.