[With Mindhunter set to premiere next week, we’re reposting our deep dives into the work of director David Fincher. These articles contain spoilers.]

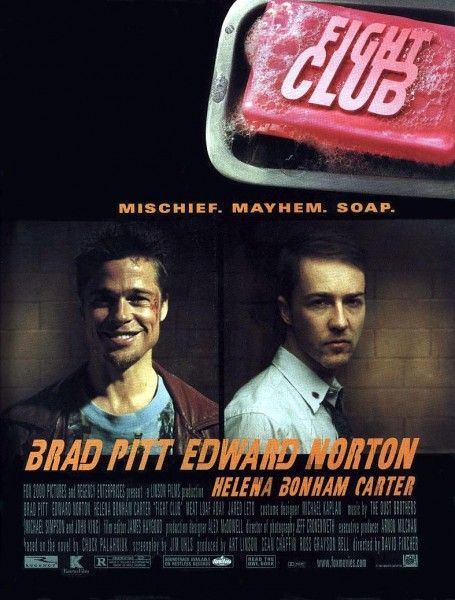

The first rule of Fight Club is to talk about Fight Club. The movie underperformed at the box office, and found life on DVD where it became a cult classic. Within the context of the film, Tyler Durden's famous rule is a brilliant and ironic bit of marketing for a group of men trying to reject advertising and find human connection. "Jack" (for clarity purposes, I'll use this name to refer to the Narrator) may be our storyteller, but Tyler is our lens, and through that lens, the story of Fight Club has been greatly misinterpreted by any audience member who saw the movie and thought, "I should start a fight club!" The movie isn't preaching. It isn't an angry screed by David Fincher or worshiping at the Church of Tyler Durden. It's not even wholly about male bonding. Fight Club is a romantic comedy as only David Fincher could tell it.

More than any of Fincher's other movies Fight Club offers itself to the widest amount of interpretations because it covers so much. It's a bit of a paradox that a director who’s known for his precision should cast his thematic net so wide, but screenwriter Jim Uhls (with an uncredited assist from Se7en screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker) did a masterful job of translating the breadth of Chuck Palahunik's rich novel into a workable script.

Fight Club can be taken as a rallying cry against consumer culture. It can be a commentary on a lost generation. It can be about a primal reduction to our base instincts. It can be a celebration of anarchy. It can be all of these things and more because the movie is specific enough to provide this information but not so broad as to invite any interpretation. But on my latest viewing, I've become convinced that more than anything, Fight Club is one of the most twisted, funny, deceptive, and perverse love stories ever seen on screen.

Jack (Edward Norton) may be our protagonist, Tyler (Brad Pitt) may be our seducer, but the key to the entire movie is Marla (Helena Bonham Carter). Before we even reach Marla, Tyler is briefly cut into single frames of the movie. He's already in Jack's mind, but only in a flash. Before they truly meet, Jack thinks he's found peace in the artificial connection of support groups. These groups don't represent a real relationship for Jack; they fill an empty hole that's keeping him awake at night. He has absolutely no sympathy for anyone else, and if that's not abundantly clear by the fact that he's crashing support groups, it's hammered home by his comment about Chloe, a terminally ill cancer patient: "Chloe looked the way Meryl Streep's skeleton would look if you made it smile and walk around the party being extra nice to everybody." Then Marla enters the picture and, "She. Ruined. Everything."

She ruins everything because he has a crush on her. "Her lie reflected my lie," Jack says. She's a kindred spirit for someone who is still too self-involved to make any kind of real connection. He fills his apartment with stuff, but his refrigerator is only filled with condiments. Jack can't create a meal, and he certainly doesn't have anyone with whom to share it. Marla reflects his emptiness back at him, and like any grade-school boy who likes a girl, he kicks her in the shins and pushes her away. He can't have intimacy with a real person.

Enter Tyler Durden. Marla is leading Jack down the path to needing someone real, but when his artificial connections at support groups begin to weaken, a wholly fake connection is even better. When Tyler and Jack meet, Jack has "woken up as a different person," and it's a person who starts calling Jack on his bullshit from the get go. Tyler knows Jack's mind, which makes him alluring from the start. Jack may not be able to explain to us why he decided to call Tyler, but it was clearly a subconscious decision to call forth a subconscious friend: Someone to get Jack to reevaluate his life rather than sell him something like a yin-yang table or a shoulder to cry on.

Their first fight is a consummation of their relationship. It's the mix of self-love and self-hatred that Jack feels bottled up inside. But before we even get the first punch, Jack reveals a few important tidbits about the movie, and lets Fincher briefly pop his head in as he alerts us to the anarchic spirit that's about to explode (not that it wasn't already threatening to overflow already with the impressive VFX work, dark humor, and sliding penguins). We're told that Tyler works as a projectionist, (i.e he works in film), and he likes inserting shots of pornography into movies. Aside from the fact that "No one knows they saw it, but they did," also refers to Tyler's earlier appearances, it's an announcement of how Fincher is going to keep providing clues that Jack and Tyler are the same person.

Yes, there are overt moments where Jack is on the phone with the detective, and when asked about a possible suspect, Tyler whispers, "Tell him the liberator who destroyed my property has realigned my perceptions," and when asked about enemies, and Jack responds, "Enemies?", Tyler quickly proclaims "who reject the basic assumption of civilization, especially the importance of material possessions!" Again and again, we're given these clues. When Jack beats himself up in front of his boss, he tells us he's reminded of his first fight with Tyler. These moments add up, especially when Tyler and Jack talk about their lives.

As Tyler's taking a bath and Jack is clipping his fingernails, they talk about an absentee father giving advice. They follow the first piece of advice: go to college. They follow the second piece of advice: get a job. But when it comes to the third piece of advice, "get married", Jack replies, "I can't get married. I'm a 30-year-old boy." So instead of properly pursuing Marla, Jack gives into adolescent fantasies. He chooses to beat up other guys and let his imaginary friend handle the sex. Jack can't accept the notion of an emotional connection with Marla even though they're perfect for each other. Note that Tyler and Marla never occupy the same space as Jack. All three of them are never in the same room. Again, part of that is the twist, but it's also the warring factions of his dark, twisted Peter Pan luring him to play with lost boys, and a woman who may be deeply fucked-up, but she's also attracted to Jack and he can't see it. All he sees is a reminder of his parents and feeling "6 years old again." We don't need to see a flashback to Jack's childhood because he's giving us all we need to know—he has no idea what a loving relationship looks like and how that requires maturity. Far better to reduce life to the simplicity of beating up other damaged people, and tapping into their fears and insecurities.

Fincher's artistry makes Fight Club the perfect seduction. Aside from expertly casting Brad Pitt (a handsome actor admired worldwide), we see the director's remarkable skill of turning the ugly into something oddly beautiful. It's marked not only by the dark violence, but also the constant comedy. Fight Club is damned funny, and it has to be because Tyler Durden is trying to seduce us. Tyler Durden wants to get us on his side. Once again, Fincher empathizes with the artistic master planner. This is why some people misunderstand the movie. Fight Club is not a mission statement. It is not a manifesto. It is not a treatise or a call to arms. One could point out that Fincher and Pitt are being hypocritical because they do ads and the movie rejects capitalism. First, on the commentary track, Fincher explains:

"This film probably more accurately depicts my take on advertising and what it provides for society [laughs] than any—you work where you can. I'd much rather start off making movies, but no one was much interested in hiring me to make movies early on, so I did music videos and commercials as a way to just play with the tools."

Tyler insinuates himself with the truism, "The things you own end up owning you." It taps into our understanding that perhaps we are too dependent on consumerism. We should have some desire for freedom. But it's a childish instinct to tear it all down as if consumerism was the root of all of Jack's problems or our problems. This platitude is a way of cracking open the door a bit further so, like any good cult, the leader can make things more and more radical.

When fight club becomes Project Mayhem, it's no longer about escape for Jack. It's an escalation, and his childish desires have metastasized. His friend became his father figure and now Tyler is Jack's foe. When Marla comes by, Jack breaks his promise to Tyler, and mentions him to Marla, who (understandably) is confused by the notion that "Tyler's not here. Tyler went away. Tyler's gone." It's the very first time in the movie that Jack has been vulnerable around her instead of rudely pushing her away. Ironically, it's only by following Jack's credo, "It's only after we've lost everything that we're free to do anything," that Jack realizes all of the "You are not a beautiful and unique snowflake" or chemical burns have anything to do with his real problems. Once Bob dies and it becomes clear that the cult is now self-sustaining, it's time for Jack to flee and then he hits the twist.

Marla confirms Jack is Tyler Durden. The bartender may have said it, but the only one who could make it connect is Marla. And when she asks him if they just had sex or if they made love, Jack replies, "So we did make love." This is a guy who previously relished the thought of Marla slowly committing suicide and wanting to paint the walls with his brains at the mere thought of being in her presence because the gentleman doth protest too much. This is the gleeful, anarchic, cynical, wry, winking, twisty film that only David Fincher could make. It has all of the elements we've come to expect from him, and yet one quality he never gets enough credit for is his heart (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button being an odd case study we'll get to later). Fight Club is a biting, highly quotable, acerbic, meaty film, and buried beneath all the bravado, chest-beating, snarky commentary, and declarations is a story about setting all of that bullshit aside for something real.

Tyler Durden is a fantasy. He doesn't exist. He's a rambunctious spirit eventually feeding our worst instincts until we're at his mercy or at his side. It's only when Jack decides to shoot his imaginary friend—his representation of reckless youth—in the head that he's free to grow as a human being and accept Marla. "You met me at a very strange time in my life," Jack tells her. And then they hold hands as buildings explode because love can't save the world, but it's nice to have someone at your side when the world falls apart. And yet Tyler is never really gone from this world. Jack may have let him go, but Tyler Durden is an idea. He's an idea that has persisted well beyond the movie and into every person that takes his ideas as gospel rather than demagoguery. Fight Club still looks the same at the end because we're still in Tyler's world and we'll always be in Tyler's world. There will always be the allure of rejecting all modern notions, devolving to our base instincts, and wanting to break free from the soulless office job and the cheap furniture. Tyler is still showing us the movie. He's still in the projection booth. And what do we see before we cut to the credits? "Nice big cock."

Fincher's next movie would be somewhat simpler in themes and far more difficult in creation.

Next: Panic Room

Other Entries:

- The Work of David Fincher

- Alien 3

- Se7en

- The Game

- Panic Room

- Zodiac

- The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

- The Social Network

- The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

- House of Cards and the Director's Future