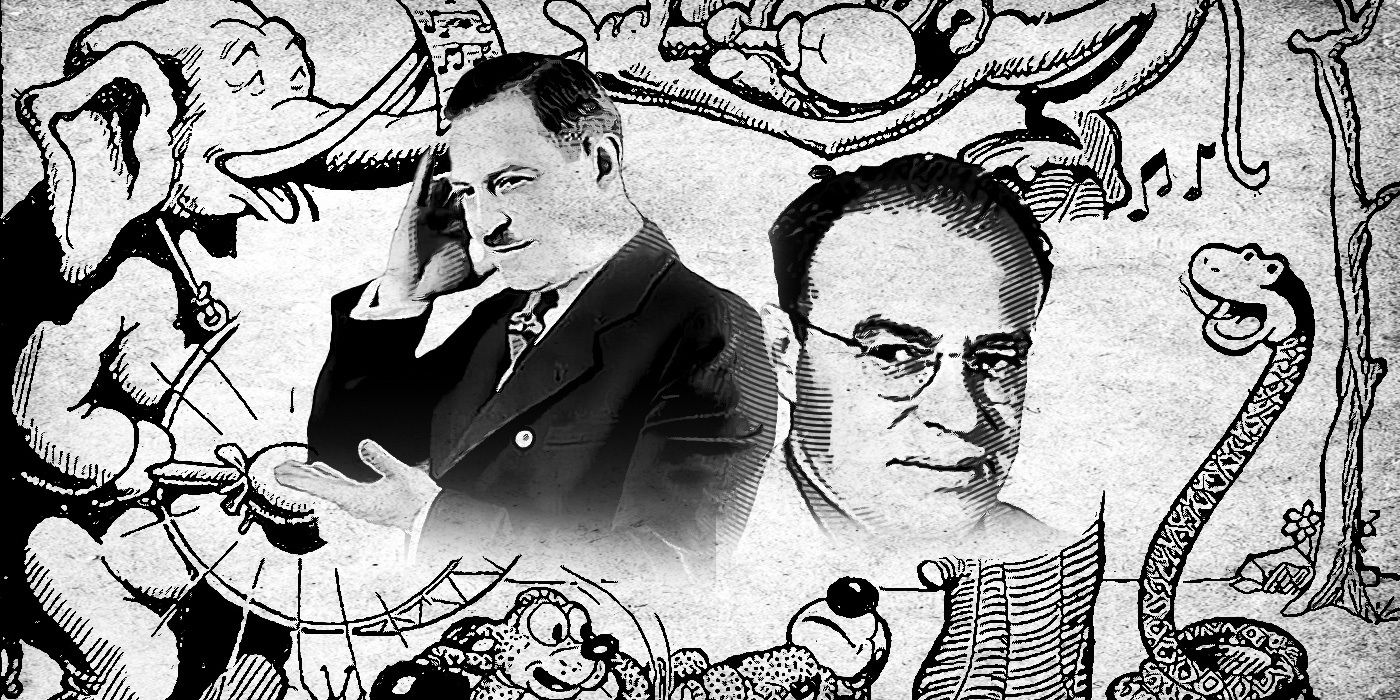

Their most famous cartoon is one of the most prominent icons of the Jazz Age. Superman first became a movie star thanks to them. Before Pixar and DreamWorks, they were the archrivals to Walt Disney in the field of animation. Yet Fleischer Studios met an ignoble end during World War II; taken over by its distributor, rebranded, and slowly exhausted. Talent, ambition, and some of the greatest cartoon characters ever created couldn’t triumph over the poor business sense and personal falling out between brothers Dave and Max Fleischer. It was a sad way to conclude what had been a wonderful success story.

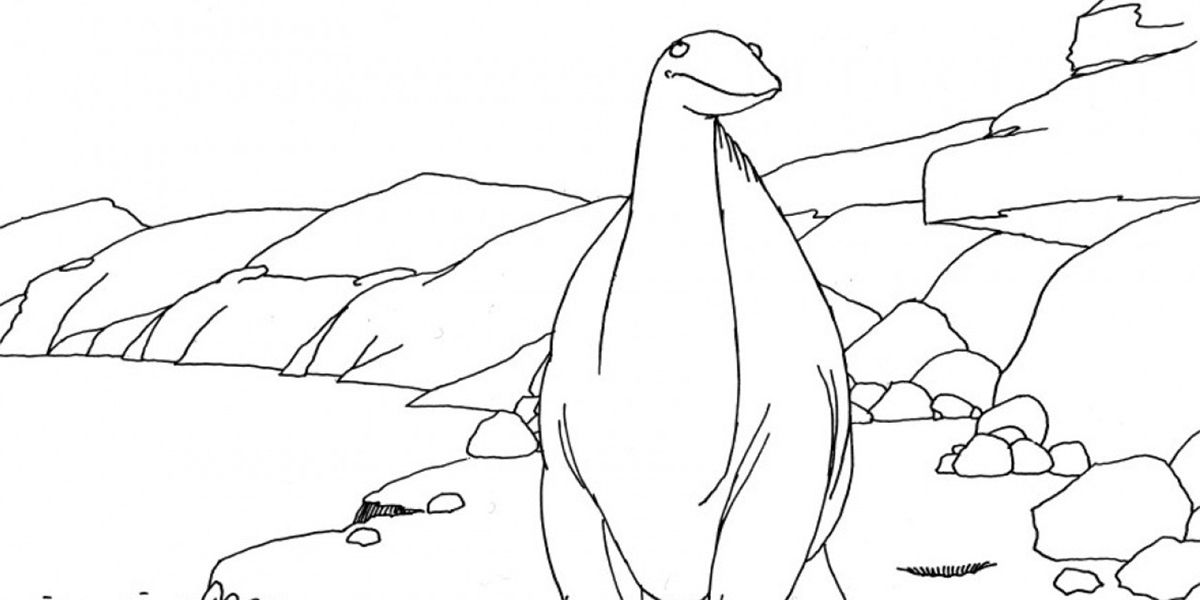

The Fleischers were pioneers in the field of animation. Captivated by a chance screening of Winsor McCay’s 1914 “Gertie the Dinosaur,” a young Max became a cartoonist for Bray Studios. An inventor by inclination, he soon developed what became known as the rotoscope, a system for projecting live-action footage so that the animator could trace the movement. Rotoscoping has a somewhat mixed reputation as a technique for cartooning; it can result in stiff and unnatural motion at odds with a character’s design, particularly when it’s employed for facial expressions. But at the time of its invention, it was a breakthrough. With the rare exception of “Gertie,” animation was a novelty in a theater program, an exhibition of simple gags, rubbery motion, and casual disregard for physics. The rotoscope allowed for a degree of fluidity and naturalism not seen before in cartoons.

To exhibit his new invention, Max partnered with his younger brother Dave. The vaudeville-loving Dave had his own clown costume for occasional performances at Coney Island, and the brothers created a series of cartoons with an animated clown stepping off the page to interact with Max. The Out of the Inkwell series and its star Koko were that lucky combination of experiment and mass public success. The films did so well that, when Bray Productions fell on hard times, the Fleischers were able to take Koko with them when they set up shop for themselves, first as Out of the Inkwell Films and then Fleischer Studios.

The rest of their siblings joined them in the venture in various capacities, but only Max and Dave were owners of the new studio. Nominally, Max was the producer, and Dave the director. They were credited as such in the cartoons. But Max maintained a public image as the hands-on paternal head of the studio and kept a strong hand in the creative end, while Dave had to be part of business affairs as part-owner. Max continued to work on inventions that Dave would employ in the cartoons. Among these was a system for having a bouncing ball run across a string of words. Used on “Sing-along” shorts that illustrated popular music, the system was the first of its kind – and the first use of sound in cartoons, an honor usually attributed to Disney and Mickey Mouse (though it must be said the sound system Disney used worked better and more seamlessly integrated with the footage).

But there was more to Fleischer Studios than singalongs and a novelty series. The Fleischers were children of immigrants settled in New York City, and as their studio grew and prospered, their cartoons reflected the swirling cultural currents of the Big Apple during the Great Depression. Betty Boop, the most famous of the characters they created, was a caricature of flappers. Her films were packed with an innocent sexuality and jazz music, often functioning as promotional venues for acts like Cab Calloway as well as standalone cartoons. The Popeye series, adapted from E. C. Segar’s comic strip, put the sailor in the slums of the city when he wasn’t traveling the world and gloried in slapstick and violence. The background art and the elasticity of the Fleischers’ characters nodded to the Surrealist and Expressionist movements in the arts. Even the studio’s method of recording dialogue, often post-synced to the animation rather than prerecorded, allowed for a more loose, improvisational approach that captured something of the New York attitude.

This sensibility was dialed back in the mid-30s, particularly in the Betty Boop cartoons. With the rise of the Hays Code, her sexual escapades were targeted by censors out for anything “immoral.” This coincided with the decline of flapper culture, a double whammy that brought an end to Betty’s screen career before the decade was out. But Popeye’s rough-and-tumble adventures continued to clear the censors, delight audiences, and give a good name to an appalling vegetable. He headlined three two-reel Technicolor spectaculars adapted from One Thousand and One Nights that also featured the Fleischers’ answer to Disney’s multiplane camera: turntable miniature sets the animated cast could move through. These Popeye shorts are some of the best cartoons of the era, and for a time, the salty old sailor surpassed Mickey Mouse in popularity and revenue.

That wasn’t the only card the Fleischers had in their favor in the competition for animation supremacy with Disney. Theirs was the older, established studio, headquartered in what was then the epicenter of cartooning. Walt Disney caught his first break in animation by inverting Out of the Inkwell’s gimmick for his Alice Comedies. But after Mickey Mouse and the Silly Symphonies, Disney’s star shone the brighter within the industry. The studio’s reputation for quality and pushing the boundaries of the form, its location in sunny California, and its many job openings lured artists from around the country – New York included. Several Fleischer men defected to Disney, where virtually every technique in the animator’s repertoire was refined and perfected (if not invented), and later dispersed through the industry. Walt also enjoyed the good fortune of having his instincts for an exclusive deal for three-color Technicolor and the viability of a feature-length cartoon paid off.

Of course, Walt could gamble on such things thanks to his independence. Max had also seen the possibilities of color and full-length features. But since the mid-20s, he and Dave had not been masters of their own studio. An agreement with Paramount for financing and distribution came at the price of control. The larger studio was badly affected by the Great Depression; its 1933 bankruptcy was one of the biggest and most complex in the country. Such financial restraints regularly tied Max’s hands. Only after Disney broke ground and made money on each new concept would Paramount relent. They weren’t above pulling one over on the Fleischers if they could either. When studio vice president Emanuel Cohen was sacked, he tried to warn Max about the unfavorable position his deal with Paramount put the studio in and offered to act as the Fleischers’ distributor. Max, burned by past experiences and with a sense of loyalty to Paramount, turned Cohen down.

The Fleischers’ reliance on Paramount was such that the distributor could pressure them on content. At the height of production, the studio put out a cartoon a week, a grueling schedule for even short animated films. As Disney became more successful, Paramount asked for films in the Disney vein; the results were predictably derivative and unimpressive. And when it came to the hit series Popeye, Paramount was unwilling to allow more time and money even as they clamored for more entries.

All these pressures affected morale and working conditions at Fleischer Studios, an issue Max and Dave ignored until it was too late. The studio saw the first major animation strike in 1937. Partially to escape to a place with less union presence and partially to try and match Disney’s appeal of a better climate, the Fleischers prepared to relocate to Miami. Besides the weather, the tax incentives and the chance to build a new, state-of-the-art studio were enticing. But to afford the move and the construction of their new plant, the Fleischers relied on Paramount for funds – and if things didn’t work out, it would only be the Fleischers on the hook.

With all these creative and business tensions swirling around them, the relationship between Max and Dave began to deteriorate. The brothers were disparate personalities, Max paternal and intellectual while Dave was outgoing and streetwise. Both men had creative egos that began to clash over credit and content; according to historian Ray Pointer, Max was prepared to let their option on Popeye expire and move on to more serious filmmaking, while Dave thought it ridiculous to abandon their biggest star. When Dave acquired full control of the production of the cartoons in 1939, he blew up the size of his name on the title cards and cut Max out of any creative involvement. There was personal animosity between the brothers as well; Max resented Dave’s conducting an affair with his secretary. Tensions between the two reached the point where they communicated to Paramount that they could no longer work together and ceased speaking.

With this poison in the atmosphere, the move to Florida was never going to be the fresh start the Fleischers had hoped for, but relocating itself proved a poor business decision. It put them further away from vital facilities in New York and never delivered any cost reductions. The move coincided with the Fleischers’ attempt to finally break into features with Gulliver’s Travels, for which Paramount provided less money and a fraction of the time Disney gave to Snow White. Worse, they deliberately withheld information about the film’s performance ahead of contract renegotiation. Under Dave’s direct supervision, the non-Popeye shorts began losing money. A potential lifeline via the Man of Steel resulted in nine excellent Superman cartoons that expanded his leaping tall buildings in a single bound into flight – but not enough income to meet the Fleischers’ debts to Paramount.

The final straw came during the production of the Fleischers’ second and last feature, Mr. Bug Goes to Town. Similarly, rushed as Gulliver’s Travels had been (and just as lackluster in every respect except animation), Mr. Bug had the misfortune to premiere in the wake of Pearl Harbor. In that environment, a simple story about bugs trying to move couldn’t capture the public eye; the film flopped. Dave jumped ship at the end of 1941; Paramount asked for Max’s resignation shortly after. They acquired the studio, reconstituted it as Famous Studios, and exhausted Popeye, Superman, and every series they began themselves into formulaic exercises until the studio folded in the 1960s.

Cut off from their studio – and the rights to their films – the Fleischers drifted out to California. Dave briefly produced cartoons for Columbia and Republic before ending up a technician at Universal, while Max largely withdrew into his inventions and teaching. Separately, they brought suit against Paramount over credit due them for their films but were foiled by the statute of limitations. And personal animosity lingered along with professional frustrations; through his son Richard Fleischer, Max made peace with Walt Disney, but he and Dave never reconciled.