From the dawn of the medium to the modern-day, forced perspective has been used to create a magical, mind-boggling effect, tricking the eye into believing giants or Lilliputians could walk among us (Gulliver's Travels), that Elijah Wood is dwarfed by Sir Ian McKellen (The Lord of the Rings trilogy), or that Will Ferrell is surrounded by elves (Elf). It is truly remarkable that a technique so simple maintains ongoing popularity with modern filmmakers, but the effect can be so convincing, audiences may think they are looking at computer-enhanced imagery rather than one of the oldest tricks in the book. So, how does it work?

At the most basic level, forced perspective is the act of filming two subjects with a lens capable of a considerable depth of focus, with one subject kept in the very foreground and the other far away. This creates an illusion where the closer subject now appears to be giant, or alternatively, the further subject appears to be a miniature. A good example of this can be found in the classic Kids in the Hall sketch where a strange man hides in a park “crushing” people’s heads by holding his thumb and forefinger close to the lens and framing their heads, so they appear to get squashed. However, the effect can be made significantly more complex and convincing with the use of different sized props, clever camera angles, and other movie trickery. Let’s have a look at some of the most striking examples to date.

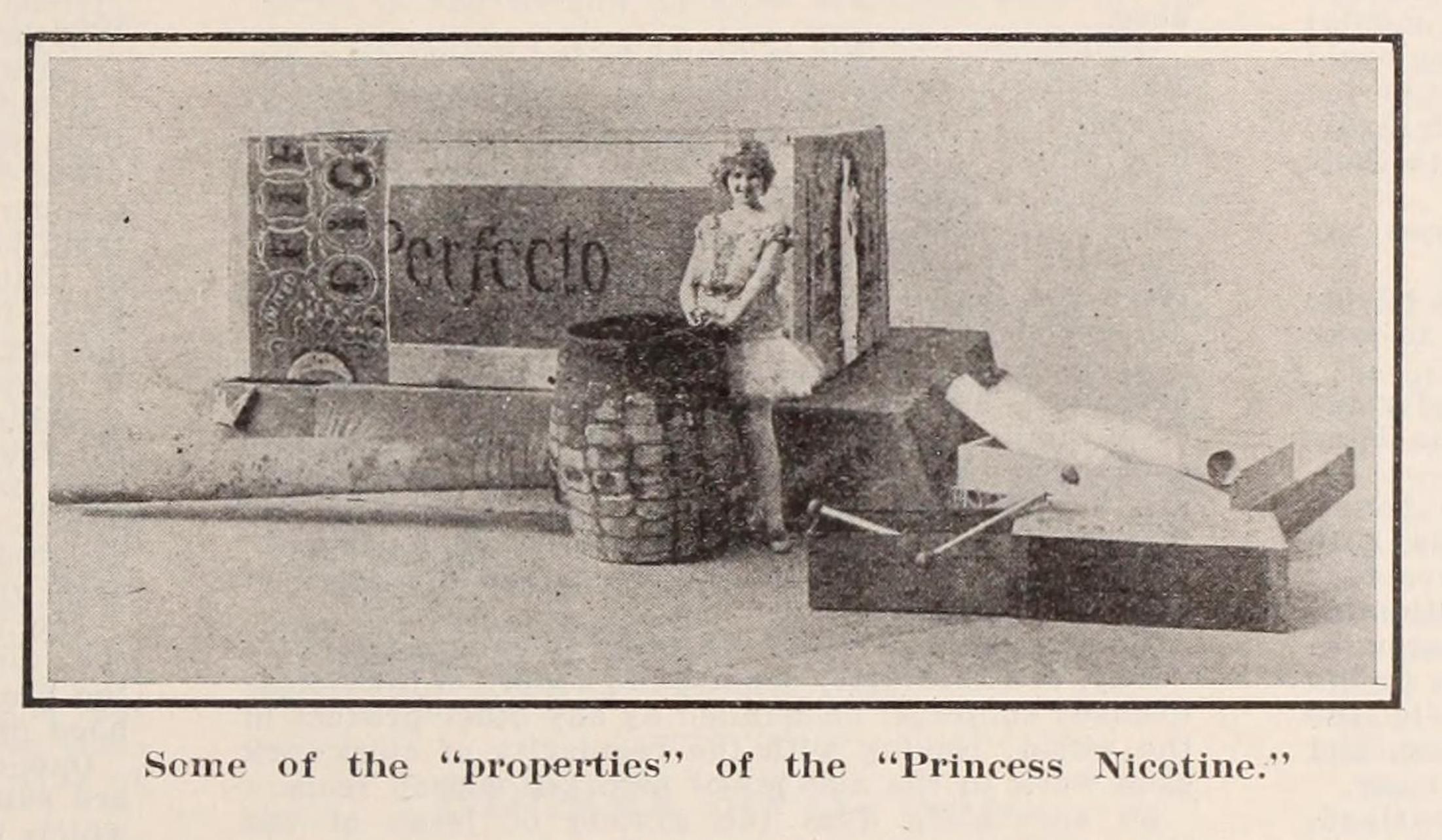

Many early films were, in essence, magic tricks. Following in the legendary footsteps of the genius Georges Méliès’ imaginative shorts, formative filmmakers had to be consistently inventive to come up with new special effects, to create imagery audiences had not seen before. In Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoking Fairy (J. Stuart Blackton, 1909) a series of striking shots are brought to life with a variety of ingenious camera and editing tricks. A man packs tobacco in his pipe, but yawns and falls asleep rather than smoke it. Two tiny fairies then emerge from his tobacco box. Blackton cuts to a closer view of the fairies, who are now surrounded by giant props of the box and the pipe, as they proceed to play tricks on the smoker. The effect of the miniature actors climbing out of the box was achieved by the actresses’ images being reflected in a mirror placed on-set in the far distance. In the days when literally any image can be conjured on a computer, modern audiences may be too jaded to enjoy the simplicity and effectiveness of this shot, but audiences at the time must have been blown away, and the effect does hold up remarkably well.

Forced perspective evolved during the 1920s and 1930s, as it was frequently employed by silent film comedians to make their death-defying stunts look more dangerous than they actually were. For example, the iconic scene of Harold Lloyd hanging from the clock-face in Safety Last! (Fred C. Newmyer & Sam Taylor, 1923) was achieved by constructing a fake wall atop a tall building and angling the camera so that the cars and people in the street below looked miles away. It appears Lloyd is risking falling hundreds of floors to his death when in reality he was only a few feet away from solid ground.

Another variation of the evolving effect that also stands up today can be found in Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) in the famous roller skating scene. Chaplin repeatedly skates close to the edge of a large drop, circling closer and closer to a dangerous fall before almost losing his balance and going over backward. In fact, Chaplin was never in any danger; the drop was actually a matte painting on a sheet of glass placed close to the camera, with the set marked in order for Chaplin to know exactly where to place himself to best create the illusion. It is so simple, and yet flawlessly executed. This technique went on to become the basis for building upon the scenery in countless fantasy and adventure films prior to the invention of computer effects.

Forced perspective showed no sign of waning as the years rolled on and talkies, then color films began to become the norm. In the 1950s there was a fleeting trend for Lilliputian-style characters in such films as Disney’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People (Robert Stevenson, 1959). Whilst no amount of movie magic can atone for the amount of bad Irish accents and stereotypes on display throughout, nevertheless, Darby O’Gill contains some of the most sophisticated forced perspective shots ever put on film. To sell the illusion that leprechauns were real, Walt Disney commissioned and starred in a marketing campaign that claimed he had negotiated with real-life leprechauns to star in the picture.

This is reasserted in the opening credits with Disney’s playful message - “My thanks to King Brian of Knocknasheega and his leprechauns, whose gracious co-operation made this picture possible.". His team of effects wizards used forced perspective extensively and in a variety of pioneering methods to sell the gag visually, including matte paintings, giant props, and complex sets. Most notably, they placed the actors portraying leprechauns four times farther away from the camera than Darby. The set was split in two, with the “little person” surrounded by a four-times enlarged copy of the set and props. With carefully implemented lighting, the in-camera effect was that the two images blended perfectly together with no obvious sign of how this had been achieved. The basic principle of this method was the same one used to create the Hobbit effects in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (Peter Jackson, 2001) over 40 years later.

The notion of toying with the viewer’s understanding of the language of cinema and perspective for comedic effect was mined for all it was worth by Jim Abrahams, David and Jerry Zucker (ZAZ) in their underrated 1984 comedy classic, Top Secret! In one scene, we appear to be watching from inside a train as it pulls out of the station before it is revealed that the train is not moving, but instead the station is driving off on wheels. Later, a man’s eye appears magnified through a looking glass; he drops the glass to reveal his eye is actually massive. But it is the two forced perspective gags that get the biggest laughs in the movie: one very subtle, the other absolutely huge. In the first, we appear to be viewing some cows through binoculars, demarcated by black lines around the frame, only for the cows to leap over the lines revealing that in fact there is a large, black board with holes in it creating the binocular effect. Perhaps the best gag of the movie is also a perfect distillation of the concept of forced perspective: a telephone rings in the foreground, taking up most of the frame, and a soldier walks towards it from the background, gradually revealing that the phone is in fact gigantic.

Forced perspective remains as popular as ever. This century there have been examples as wide-ranging as the aforementioned Lord of the Rings trilogy, Elf (John Favreau, 2003) Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Michel Gondry, 2004), and art-house fare such as the work of Roy Andersson, who makes extensive use of matte paintings to fool the eye and create his woozy, dreamlike atmospheres. Computer Generated Imagery, complicated animatronics, and time-consuming make-up effects are excellent tools in any filmmaker’s arsenal and always have a place in cinema, but sometimes the cheapest practical effect can produce the most startling, memorable results. It turns out the earliest filmmakers had some pretty nifty ideas — long may they continue to influence the craft.