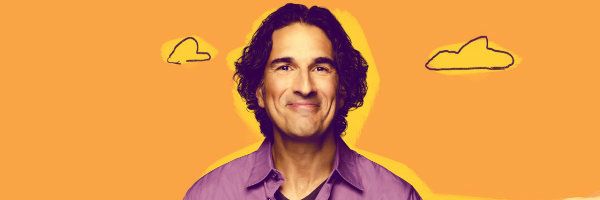

Every night, in comedy clubs across the country, comics bare their souls onstage. They dig deep within themselves to make people laugh, to distract them from their troubles and, for at least a few minutes, take away their pain. But sometimes it's the comedian who is in pain themselves, and all the laughter and applause in the world isn't enough to make them feel better. To battle the sinister force that is depression is no laughing matter. For comedian Gary Gulman, that struggle is very real, but with his new HBO special The Great Depresh, he gets the last laugh.

I've been a Gulman fan for the last seven years, ever since his 2012 Comedy Central special In This Economy? I remembered him vaguely from Dane Cook's Tourgasm back in 2006, but I wasn't much of a comedy nerd back then. His jokes about Netflix and the anti-shock function on DVD players just cracked me up, and anytime I returned home to Massachusetts, where Gulman is also from, I would play his albums for my Mom. I loved hearing her laugh whenever Gary did his impression of his own mother, chiding him "Yah nevah know Gah, yah nevah know!" as only a Jewish mother can.

The point is, I've always had a soft spot for Gulman, and when I finally got him on the phone and told him, "Gary, I had no idea you were struggling with depression," he stayed true to his nature, responding, "Well, I didn't feel it was appropriate to tell you. It would've been a bit much." The Great Depresh may not be Gulman's funniest special, but it does represent his best work. It is a special special in every sense of the word, and those are few and far between these days. Neal Brennan's 3 Mics and Hannah Gadsby's Nanette are recent examples of confessional comedy that is striking a chord with audiences — not just in their funny bones, but in their hearts and minds. This shift to a more personal style suits Gulman, whose jokes in The Great Depresh have never felt so urgent, or relatable. Because we've all felt sad, and we've all been hurt. Some just bounce back differently than others.

With The Great Depresh, plus a fun cameo in Todd Phillips' hit movie Joker (read a great story from the shoot below!), it's safe to say that Gulman has bounced back. He has a pep back in his step again. He knows full well that he'll likely spend the rest of his life bravely fighting this fight, but the difference now is that he has seen the light at the end of the tunnel, so he knows that one exists.

If you're struggling with depression or thinking of harming yourself, call 1-800-273-TALK. And if you don't want to talk to anyone, maybe give The Great Depresh a watch, or listen to one of Gulman's albums, because I bet they'll put a smile on your face. Enjoy our candid chat below.

For starters, I was inspired by you sharing your battle with depression in this special, and I think it's going to help a lot of people.

Gary Gulman: I've heard from so many people saying that it did help them. I did hope that, and I've always said that if it helps one person, it'll be worth it. And it seems to be doing that, so I couldn't be more grateful.

Where would you say that your comedy comes from?

Gulman: Well, from the beginning, I think I wanted to be the comedian that I would want to see. So, starting when I was 13, my Mom took me to see The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, because I'd been a fan of that show and all the comedians that went on, and that was the first time I ever went to a live comedy show, and I was just mesmerized by it. Garry Shandling was the standup guest. I mean, I had been hooked since I was 7, so that really cemented my obsession and my passion. From there, I went to shows with some friends in Boston when I was in high school, and then in college. I remember on New Year's Eve of 1993 -- well, it was actually 1992, but you understand -- I saw a comedian at the Comedy Connection in Boston, and I decided that the next time I went to a comedy show, I was going to get onstage and I was going to try and do an open mic. The following summer I went to a couple of open mics just to watch and figure it out, and then I started onstage in October of 1993, so about 10 months after I saw that show. I had decided to do it and I did it, and I was hooked. It went well, and I knew, this is what I'm going to spend most of my time pursuing from here on out.

I'm the oldest of three boys, and I understand you're the youngest of three boys, so I'm curious how being the youngest influenced your sense of humor, and also, if being a child of divorce had any influence as well.

Gulman: I think there were a couple of things going on there. My brothers were much older than me, they were 13 years and 10 years older than me -- and they still are. And I remember how it felt to make them laugh and entertain them, and it felt so good. I'm sure there was some chemical response where I was getting some dopamine or serotonin or whatever, but I loved the attention and making them laugh, and laughter was really valued in my family, so I tried to bring as much of it as I could. I also think there was probably some sadness following my parents' divorce, and I tried to lighten the mood a little bit. But mostly, I think I just craved attention because my Mom was busy, and when I had her around, I wanted to entertain her and make her laugh especially.

Well, before I get to my next question, I'm just going to get this over with. My Mom passed away a couple years ago and whenever I'd come back to Boston, I'd play her your albums in the car. So we shared some great laughs and made some wonderful memories listening to you, and I wanted to thank you for that, on behalf of both of us.

Gulman: Jeff, that makes me so happy to hear. My Mom's still alive but I lost my Dad, and we went to see Jay Leno at the North Shore Music Theatre in Beverly, and that was one of the greatest times, just sharing laughs and that evening with him. But even just listening to albums with them growing up, and watching comedy on TV. Laughs are a great thing to share. It's really nice.

So, speaking of sharing, what inspired you to be so honest and forthcoming about your battle with depression in your latest special. How do you decide, this is the one where I'm going to bare my soul.

Gulman: I mean, it was gradual. I think that initially, I talked about depression and anxiety onstage out of necessity. I was so clearly messed up that I had to address it onstage. It was at the Comedy Studio when it was in Harvard Square in Cambridge that I started to really talk a little bit about my mood difficulties, and I sort of unclearly alluded to it, but I never really got specific or was all that explicit. If you were depressed, then you got it, but if you weren't, you wouldn't even pick up on it.

I was ready to get back onstage. I felt well enough to try and do some work. I knew that I had to adjust my attitude towards it, because my mood for a long time had been completely dependent on how my last show went, and I knew that I had to get rid of that mindset. But if I wanted to do standup at that point, I felt it was important and necessary to address that I was clearly not right, that I was off. My hands were shaking, and my posture [was off], and you could just tell something was off about me. So I just started to talk about my mood and how my day was going, and a lot of my symptoms, and how I was handling it. And the blessed thing was that the audience responded to it, and after the show, comedians and audience members would approach me and tell me I was doing something helpful, so I got a lot of positive feedback and encouragement and support.

The owner of the Comedy Studio, Rick Jenkins, was so nurturing and encouraging in me talking about those things, and he allowed me to have nights where it didn't go that well, and where I was struggling. And you can see that at the beginning of the special. But I started to get encouragement and positive feedback, and that caused me to elaborate and extend the discussion, and then my manager, who's just so perfect, both as a manager and as a partner in creativity, he said, 'you should really pursue this vein and continue to write about this because it's different and it's interesting and it's funny.' And that was the most important thing.

I didn't want to be a one-man show monologist. I love that form, but it's just not comfortable to me. I'm most comfortable when I'm getting laughs, and while I don't need a constant laugh-track going on, and it's good to have some points in the show where I'm being serious and I'm not getting laughs, ultimately, I'm a standup comedian and I want to service that form. So I got all kinds of encouragement. It wasn't particularly brave. There were nights where it didn't go well, but there were always people who were there to tell me to keep at it and stick with it. You'll figure it out. And then I became one of those people. I got well enough to figure it out. I've always figured out how to make things funny, and this wasn't that much different. I was going to figure it out, so luckily, my recovery coincided with this idea, and eventually my manager introduced me to Mike Bonfiglio, who directed the special, and he helped to guide me in turning it into the type of special we wanted to do, where we informed the standup with some documentary footage. He helped me design the content of the set, and also the narrative that we told, and he helped me as a storyteller to figure out how to get it across, and where we would break it up with the documentary based on the beats and the points that I had to make. So it was a group effort, and beyond just the people involved in creating it, I also had audiences and other comedians and fans who were so supportive, and gave me so much encouragement, and made it quite clear that I was doing the right thing and that I was on the right track at all times, even on nights where it felt very uncomfortable to go out there and then the audience was not that responsive. Even some nights when I would say, 'oh my God, that was really tough, and the audience wasn't really enjoying that,' there were inevitably hundreds of people who would say it was a really special show. So I knew we were onto something special pretty early on.

How important was it for you to have your mother be part of this special? Was she worried about being in front of the camera, or did she have fun with it? I'm just curious about her involvement.

Gulman: When I brought it up, she pretty much said, 'no, I can't do it.' And I said, 'just talk to the director, Mike Bonfiglio,' because he's such a nice, thoughtful, kind guy, and he talked her through it. So she said she would do it, and then she was so anxious and dreading it, and at first it was hard to get her to talk and elaborate. I know the first time I did an interview, I was just answering 'yes' and 'no,' and not giving any interesting interviews, but she figured it out pretty quickly, and I thought her portion of the show was really illuminating. I think she kind of stood in for most of America from that era and that position. They weren't aware of the symptoms and signs of mental illness. I thought she was a very important part of the narrative, and she got across the knowledge and the philosophy of people of that era, but also provided some great laughs.

How did you link up with Judd Apatow and what kind of support did he offer you while you were going through this?

Gulman: Well, Mike had done a number of projects with Judd, so in the first meeting we had when I told him what my idea was, and he sort of said what he would want to do and how he would want to approach it, he also said, 'I also think Judd Apatow would be interested in this, and if you don't mind, I would love to run this by him and see if he would want to be the Executive Producer of it, and sort of shepherd it. And also, his reputation and his imprimatur is very valuable.' So I recognized that, and I knew Judd from the Comedy Cellar, where we'd worked together a lot, and while I didn't want to bother him, because I'm sure everyone's asking him for something, I had a friendly relationship with him, so we knew each other. Shortly after Mike and I decided to work together, Judd came on and he provided a lot of guidance as to the storytelling and also the approach to selling it to HBO, because ultimately, we needed a platform for it. In the first meeting we had, we knew that the ideal partner, before any other outlet or platform, was HBO, given the way they handle things and their generosity. Their reputation was really helpful, and their experience in dealing with these types of things, and the way they promote things. So Judd was pivotal in selling it, but also in guiding us in how to make it better at each step. He had some really great notes in the editing room that made certain contrasts more powerful.

You're not someone who goes after people in comedy, which is something i've always found refreshing about you, but I have to ask, what are your thoughts on the current state of comedy and how politically fraught it is. I know that's a big question...

Gulman: I have a couple of ideas regarding that. It seems that there are a lot of people saying that you can't say anything, but they're saying that you can't say anything on Netflix, where they're receiving $20 million dollars or more for their performance, and I find that ironic. And the idea of comedians complaining about how sensitive audiences are is also ironic because I've never been around people who are more sensitive than comedians. I mean, when you think about it, we spend our days overreacting to petty injustices and running around the city complaining about them to perfect strangers, many times at a financial loss.

It's an issue for certain comedians who feel like they can't say things, but they can, they just can't say them on huge platforms. Even people who are in politics are saying that political correctness is bad, but the President was so politically correct that he felt that he needed to say that there were "good people on both sides" of the Charlottesville protests, and one of the sides was Nazis. He thought there were good people amongst a group of Nazis, and I can't think of a more politically correct statement than that, trying to cover for Nazis. So it just doesn't really resonate with me, and the freedom of speech aspect of it... to fight for the right to say cruel things, or racist things, I don't know that that's what the forefathers were envisioning when they wanted to protect free speech -- that they wanted to protect misogyny and homophobia. I don't know. It's complicated, but at the same time, I don't know that bashing homosexuals and transgender people is the hill I would want to die on.

I have to ask you about Joker and how you came to be cast in that film. Did Todd Phillips always want you to do your act, or did you get to pick which bit you did in the film, which is a big one for Collider fans.

Gulman: It is big, but it wasn't even the biggest thing I did that weekend, isn't that crazy? You'd think being in Joker would be the biggest thing of the weekend, and it wasn't! But I didn't even know I was up for the role. The casting director was familiar with my work. I don't know the whole story, but it seems that my agent made the casting director aware of my work, because they must have been looking for a comedian who was experienced, but not famous, because I think it would've thrown the people in the theater. I don't know what the thinking was as to why they didn't want to go with someone famous for the role of that comedian, but I found I had it before I even knew it was a possibility, so it was really the best way, because I know that when you audition for things, you get disappointed, you worry, and in this case, I didn't even know I was up for it.

Todd chose it off videos that he saw of me, and then he called me and asked, 'what would you want to do for a joke? The only thing is, it can't be something that's not time-appropriate. You can't be doing jokes about cell phones or the internet because it's not of that period.' So I suggested this joke about role-playing, where I'm a professor, and he said 'okay, do that one.' So I went in a few days early to get fitted for a suit, because they made me a period suit, and then I went in. Other than talking over the scene with Todd a little bit, I didn't really have to do much. They gave me two pages of the script, because they didn't want the whole script out there. It was really exciting and he was super nice and it was easy to film.

The one thing I will say that was a little bit irritating is that when I was running through my set, there were all these extras, and they'd clearly been told that I was doing well, so they were laughing and enthusiastic. And there was one extra who was so enthusiastic in his laughter that it was throwing off my timing. He was just laughing too loud, and right when I was about to say something to Todd about maybe getting the guy not to laugh so loud, I realized that it was Joaquin Phoenix. It's my best Joker story. I can't believe it took me six takes to figure out that the man with the really bizarre laugh was the Joker.

What has been your reaction to the spectrum of reactions to that movie? Do you think it has gotten out of hand and people should just the movie speak for itself?

Gulman: Man, I loved it, and think it's one of the greatest acting performances I've ever seen. I'd have to go back to Daniel Day-Lewis in Lincoln or Joaquin Phoenix in The Master to remember a performance that was so dynamic. It was like no other movie, and it certainly wasn't like any other comic book movie. It was more along the lines of Taxi Driver than it was any of the Batman movies, so I can understand where some people are into thinking that it... I don't know, not glorifying, but giving some understanding to a violent man, and dismissing his violence, but at the same time, to me, it seemed more like a very tragic story of a person failed by society, but also, the health care system, and particularly the mental health care system.

I remember in my 20s not having enough money for insurance, and having to go off my medication because I couldn't afford it, and that's so dangerous. This was a guy who was in crisis. It might be interesting to see the story of a man who has a breakdown and doesn't become a supervillain, but as far as supervillain origins go, just knowing what I went through coming up in standup, that a supervillain becoming that way because of how frustrated he was as a stand-up, made sense to me when I was in my 20s. I never thought of going out and murdering anybody, but I can see losing your grip because you're so frustrated as a stand-up, and it can be so lonely at times in your failures.

Any art requires some initial delusion, because you have to think that you're going to be good at it initially, when there's no indication or evidence that you are even competent at this thing. I look back at what I was doing early on, and there's no way you could say, 'well, someday this man will be able to carry an HBO special.' I would say, 'you must be out of reality.'

Do you have any aspirations to star in your own sitcom?

Gulman: Well, over the years I've developed sitcoms with networks, and it can be very heartbreaking because you put all your effort into writing it, and coming up with it, and you work with a writer, and sometimes they just pass, and you don't even get a final "no." It just disappears. So while it's quite lucrative, in the end, it's disheartening. Right now, I'm working on a project with a couple of writers, but I don't need it in order to feel successful. The case used to be, when I started off, that unless you had a sitcom, you couldn't get an audience to come see you live, and I've been able to, between the internet SiriusXM Radio and Conan appearances, I've been able to develop a fairly large, but most importantly, very devoted audience. So I'm really content with that. And if a really great idea comes along, or if this project that I'm working on now should come together, then I'd be happy to do it. But first and foremost, I'm a standup, and I still look forward to doing shows and jokes, and trying them out and expanding on them, and meeting the audience after the show. So as long as I'm mentally competent, I will never give that up, and everything else will be a side project. As long as I can keep doing standup, I'll be very content.

What were some of the standup albums or specials that were your favorites when you were coming up?

Gulman: I think the first album that I listened to regularly was Steve Martin's first two albums, Let's Get Small and A Wild and Crazy Guy. Those first two albums made him an international superstar and I was probably 7 or 8 when I was listening to those, and I loved them. I don't understand why a 7-year-old would be into Steve Martin, but it just made me laugh. And then later on, a friend of mine gave me a copy of Steven Wright's I Have a Pony on a cassette tape, and I listened to it and memorized it. And that was a revelation of joke writing. There's never been anybody like him before or since. So that was a staple for me. And then later on, I listened to Brian Regan, who had an album out when I was first starting and that was really helpful. And I also remember watching a special starring Paul Reiser that was important because he was a comedian who was talking about his life, but he didn't do voices, he just talked. And I thought, I can do that. I can talk and I can be interesting, and there were no gimmicks or hooks or bizarre personas. I thought, 'there's just a young man talking,' and I thought I could do that, so that was really helpful.

I love that you mentioned Steven Wright, because I can see his influence in your work in how much you both love wordplay.

Gulman: Yeah, that's a great compliment. I just think his brain is so remarkable and extraordinary.

I love your Netflix joke about The Cove, so what is the Netflix algorithm recommending for you these days? What are you watching over there?

Gulman: I seem to only watch two things on Netflix. Things I've already seen, so that 'Watch it Again' category. I've watched movies on there that I've seen 10 times. A lot of times I need something to distract me when I go to sleep, so I'll put that on and just listen to a movie that I've already seen. But I do like that show Hip-Hop Evolution, where they talk about the old hip-hop albums and stars, and the history of hip-hop. I'm obsessed with rappers and rap music. I just think they're so clever and interesting. I've been in love with rap music since the early '80s with Run-DMC, and then the Beastie Boys.

Who would be on your Mount Rushmore of rappers?

Gulman: My Mount Rushmore of rappers? Ugh, that's a great one. I would say Rakim, 2Pac, Eminem and (after much thought) Nas. If you had asked me six weeks ago, I would've said Jay-Z, but after he agreed to do the Super Bowl, I have no use for him. So I have to say it would be Nas. But quid pro quo now! You have to give me your Mount Rushmore of rappers.

I'm 35, so I'd have to say Eminem, Snoop Dogg, Notorious B.I.G. and probably Jay-Z.

Gulman: That is exactly right! But give some Eric B. & Rakim a listen, because I think you'll be very impressed.