Here’s why 1984’s Ghostbusters “works”: it’s a simple comic juxtaposition. You start with a big, outlandish premise—ghosts are real and they’re the forebearer of an apocalyptic event. In a straight sci-fi action movie, you would get a standard sci-fi action hero to save the day. The joke in Ghostbusters is that you have four guys who are in it as a business proposition. They’re not the most heroic characters; they’re kind of losers. They’re failed academics who started a business and became local celebrities. The juxtaposition is that you take the big supernatural hook, and you contrast it with regular guys who kind of fell ass-backwards into saving the world. From there, Ghostbusters has the freedom to be incredibly funny and utilize the different comic talents of its lead actors.

But then something unfortunate happened: Ghostbusters became beloved, not in a way that other 80s comedies are beloved, but beloved in the way a genre property, and more importantly, the way Intellectual Property (IP) gets beloved. Ghostbusters is far from the only popular comedy of the 1980s, but Trading Places, Coming to America, and Stripes aren’t films relying on big VFX and they certainly don’t have iconography that can then be marketed like proton packs or a distinctive vehicle. And when you can sell people a bunch of stuff and make their fandom connected to “the thing”, then the text itself becomes lost. Ironically, it becomes a sort of holy scripture disconnected from what the script actually says. Therefore, Ghostbusters, a comedy about four schlubs who end up saving New York City from a giant marshmallow man with lines like “He’s a sailor, he’s in New York; we get this guy laid, we won’t have any trouble!” now becomes something serious.

That’s how you get to Ghostbusters: Afterlife, which, despite coming from Jason Reitman, the Oscar-nominated director and son of Ghostbusters director Ivan Reitman, seems to miss the mark entirely in its relentless devotion to the idea of what Ghostbusters means to fans rather than that Ghostbusters actually is as a movie. For some, that may seem like a meaningless distinction, but when you watch it play out in Ghostbusters: Afterlife, you see you’re getting something far worse than nostalgia. You’re getting fan service completely divorced from any kind of story or even the concept of the thing people are supposedly a fan of. The original Ghostbusters is a comedy, and Ghostbusters: Afterlifebarely has jokes. The original Ghostbusters is about unlikely heroes, and Ghostbusters: Afterlife is about heroism being a birthright. The original Ghostbusters is knowingly irreverent and leans into poking fun at its own premise (“No human being would stack books like this.”), and Ghostbusters: Afterlife is all about reverence.

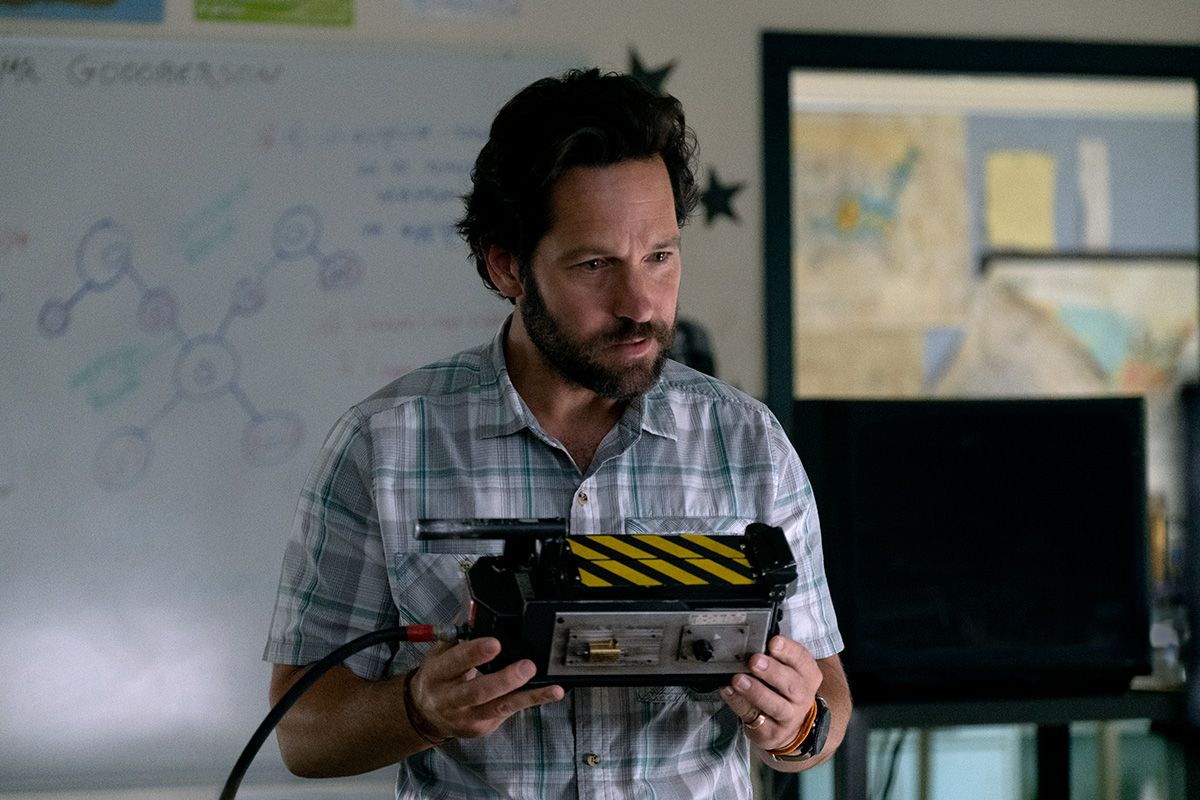

Callie (Carrie Coon) is the struggling mom of teenager Trevor (Finn Wolfhard) and precocious genius Phoebe (Mckenna Grace), and they’ve recently been evicted from their home. Callie’s mysterious and estranged father just died and left her his dirt farm in Summerville, Oklahoma, so the family goes to the middle of nowhere to try and figure out what to do next. Trevor takes to restoring an old Cadillac he found in the barn and pining for Lucky (Celeste O’Connor) a waitress at a local restaurant. Meanwhile, Phoebe, even though she’s a genius, goes to summer school where she meets teacher/seismologist Mr. Grooberson (Paul Rudd). The two connect, along with another young student, “Podcast” (Logan Kim), especially after Phoebe finds some of her grandfather’s old tools like a PKE Meter and a ghost trap. As Phoebe discovers her family’s legacy, the town of Summerville is faced with a rising paranormal activity.

Ghostbusters: Afterlife doesn’t really have character arcs. There’s some vague notion of Phoebe, who is supposed to be an outcast because she’s nerdy, finding acceptance and a sense of self upon learning that her grandfather was a ghostbuster. You can kind of see Callie getting a glimpse of a transformation as she goes from someone who thought her father abandoned her to someone who realizes that he was actually a great man. You can see Trevor in this movie because if the main characters were just Phoebe and Callie, the same people who lost their shit in 2016 over an all-female Ghostbusters installment would get angry again and we simply must keep indulging the most toxic element of any fanbase because they are the most vocal. But none of these characters really grow or change that much over the course of the movie as much as they simply make discoveries about the past.

And the lack of any kind of character development isn’t necessarily a problem for a Ghostbusters movie. After all, Peter Venkman, Ray Stantz, et al. are the same guys at the end of the movie as they were at the beginning. Their experiences don’t really change them or force them to grow and that’s fine because Ghostbusters is a comedy. In place of dramatic transformation, it has characters being funny. You don’t really want them to change because they’re funny guys at the beginning and they’re funny guys at the end. If Peter Venkman loses his irreverent attitude, it becomes less funny when the woman he’s chasing (Sigourney Weaver) starts acting like a dog because she’s possessed by a demonic spirit. But if your movie has no character development and it’s not funny, you get Ghostbusters: Afterlife, which believes its chief duty is worship.

This is a weird way to position a Ghostbusters movie, but it’s a fairly common way to position any new installment of beloved IP. The legacyquel has become a dominant presence for long-running franchises, especially since the massive success of Star Wars: The Force Awakens. From a studio standpoint, it makes for a cold but sensible calculus: the original actors are too old and/or not popular enough to headline a sequel on their own. However, through the transitive property, if we “respect” the original property, we have therefore “respected” the fanbase, and so by handing the torch, we can get younger actors into the lead roles to carry the franchise forward. The past is acknowledged, the future is secured, and the franchise—the most important thing to the people financially backing the movie—can continue to print money.

Sometimes this approach works. Star Wars has always been about family ever since Luke Skywalker wanted to know what happened to his father in A New Hope. It works with Creed because it’s a character-driven narrative about a son finding a surrogate father figure while wrestling with the absence of his biological father. But Ghostbusters is a supernatural comedy about four schmoes who have no business saving the world and manage to do it anyway. It’s a film predicated on the comedic talents of its leads and then throwing them into a supernatural premise. To truly “honor” that—funny people fighting ghosts—you would get something akin to 2016’s Ghostbusters: Answer the Call. However, that movie created “controversy” in that a vocal segment of the fanbase was mad online and did not feel sufficiently honored because this fictional profession can’t have women or something. Anyway, proper reverence was not achieved, that harmed the franchise’s ability to print money, and so we arrive back Ghostbusters: Afterlife.

Ghostbusters: Afterlife does not honor the original movie; it honors the fans of the original movie, or at least whom these fans imagine themselves to be. These are people who have the jumpsuits and the proton pack replicas and can quote the original movie chapter and verse. For them, that’s what matters about Ghostbusters—the objectification of the thing, not its essence. A supernatural comedy is all well and good, but it’s more important that the new characters revere and respect the old thing like the fans do. But in this constant respect, they miss the soul of what Ghostbusterswas, which was trying to make people laugh. Afterlife has a smattering of jokes, but my audience was largely quiet during the screening. The comedy in Afterlife is secondary to the reverence.

It’s not impossible to have characters revere the past (again, see The Force Awakens), but if they’re going to do so, they need to have strong arcs of their own where the exploration of the past propels them forward on their own journey. Callie, Trevor, and Phoebe are ostensibly a family, but Afterlife treats them more like tourists in a Ghostbusters museum. There’s no texture or nuance to the relationship between these three characters, and Afterlifemoves quickly to move them in their own directions with Trevor hanging with Lucky (and not having any kind of arc to speak of), Callie coming out of a room in her father’s dilapidated farmhouse whenever she is summoned by other characters, and Phoebe really driving the action forward in so far as she’s the person figuring everything out and is clearly designed as Egon’s heir apparent. But that’s not a family beyond “genetic descendants to whom I bequeath my stuff.”

That feels where Jason Reitman is as a director with this movie. A filmmaker who was making exciting works with Thank You for Smoking, Juno, and Up in the Air, Reitman hasn’t really had a smash hit in over a decade although I would argue that films like Young Adult and Tully are pretty great and Labor Day and Men, Women & Childrenare treated too harshly. Reitman needs a hit, Sony Pictures needs Ghostbusters to be an ongoing franchise, and fans want to be paid proper reverence, not by what 1984’s Ghostbusters actually was, but what it has come to mean to them over the past decades. But this mix means everyone loses their personality along the way. Reitman’s direction is anonymous beyond his last name and a story about inheritance, this Ghostbusters lacks any personality outside of the Mckenna’s memorable performance, and the fans get some primo pandering where enjoyment is based on cameos and spotting Easter eggs rather than respecting your audience enough to give them a worthwhile story. I can’t help but wonder if this is a movie Jason Reitman really wanted to make or if it was a movie he felt he was forced to make at this point in his career.

Either way, the message of the movie is that Ghostbusters is too important to be left to just anyone; it must be placed in the hands of those who will respect and cherish it. When you’re working in the realm of grand myth or character drama, you can get away with that, but 1984’s Ghostbusters is neither of those things. Ghostbusters: Afterlife ends up being “for the fans” in the worst sense of the term because Afterlife is a celebration of being a fan rather than the film that is supposedly being celebrated. That’s a sad reflection on the state of fandom because while Ghostbusters doesn’t always have to be a comedy about four regular guys fighting ghosts, it seems off to have it be a family dramedy that’s not really about family and not really funny and doesn’t have dramatic stakes. All that’s left is a collection of references designed to be revered. It’s a reanimated corpse shambling around, begging for your approval.

Rating: D-