Without meaning to, the 1992 adaptation of David Mamet's Pulitzer Prize-winning play and subsequent movie adaptation Glengarry Glen Ross inspired a generation of sales bros to repeat Alec Baldwin's famed Always Be Closing soliloquy as something akin to a spiritual mantra. Following the play's smash hit debut in 1983, inevitable comparisons to Arthur Miller's classic Death of a Salesman quickly followed, and persist to this day. However, far from the existential memory play about a desperate working man, David Mamet's work concerns different levels of the con game. The characters in Glengarry Glen Ross may be salesmen, but they have to work their marks like any grifter. At times, the marks can even be each other.

The film Glengarry Glen Ross endures thanks to Mamet's meaty script, working in tandem with a group of amazing actors. The MVP, however, is director James Foley. Having previously helmed the superior '80s thrillers At Close Range and After Dark, My Sweet, Foley managed the rare feat of transforming an intensely talky play into a gripping piece of cinema. Awash in bold reds and blues (cinematographer Juan Ruiz Anchía deserves special mention), Glengarry Glen Ross is full of cold, rainy spaces where the men involved find themselves continually driven to desperation while drenched in red neon.

As the film version of Glengarry Glen Ross turns thirty years old, let's take a look at the various layers of the con which exist in the story.

Many of David Mamet's Plays Explore the Con Game

David Mamet's early plays vary in their subject matter, but all of them share a species of lived-in language and regional jargon which stood out at the time. His first film as a director, 1987's House of Games, follows a psychiatrist (Lindsay Crouse) as she becomes enthralled with a con man (Joe Mantegna) and drawn deeper into his world. Featuring the likes of famed illusionist Ricky Jay and character actors like J.T. Walsh and Mike Nussbaum, House of Games reveals Mamet's overt interest in the many layers of the con game.

The key scene in House of Games finds Mantegna's smooth grifter schooling Crouse's character on how a con really works. They stake out a Western Union office until a young Marine (William H. Macy) walks in, expecting a wire transfer from home. Mantegna strikes up a conversation, dropping enough Semper Fi jargon to convince Macy he's a fellow Marine. Both bemoan the wait for their money, until they form a pact: the first to get their transfer will help the other out. Naturally, Macy's comes through, and when he offers Mantegna money, the grifter refuses. This was a lesson, after all.

And what is the takeaway? As he tells Crouse, it's called a confidence game. Because you (the mark) put your confidence in me? No. I put my confidence in you. In Glengarry Glen Ross, this confidence reversal plays out in three key scenes, with the word "con" never once uttered.

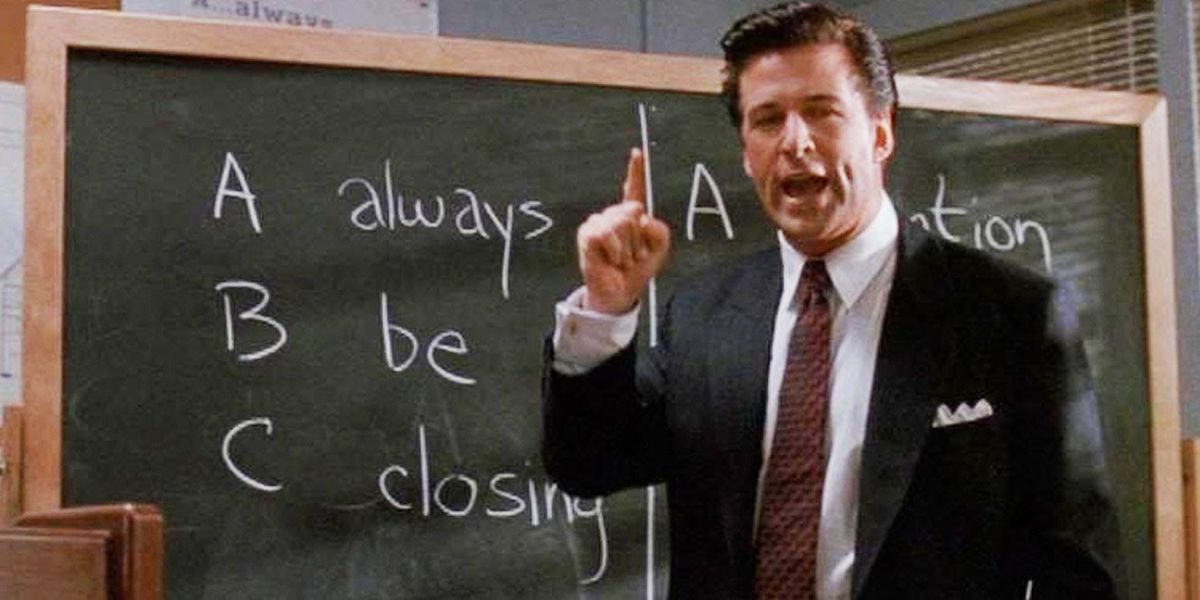

Alec Baldwin's "Always Be Closing" Monologue Is One of Cinema's Best Setups

Foley's film opens with a quick introduction to the characters in a Chinese restaurant across the street from their office. Shelley "The Machine" Levene (Jack Lemmon) is desperate for a deal, as his daughter is in the hospital. Dave Moss (Ed Harris) is a bitter loudmouth, angrily complaining about the quality of the leads to John Williamson (Kevin Spacey), the company man office manager. The smooth and confident Ricky Roma (Al Pacino) — currently top name on the sales board — eyes a mark in the restaurant bar, a middle-aged guy named James Lingk (Jonathan Pryce).

Back in the office, George Aaronow (Alan Arkin) bemoans a sale he let slip through his fingers as an unknown fella in an expensive suit appears. This is Blake (Alec Baldwin), a role Mamet wrote specifically for the screen. Alec Baldwin embodies the cutthroat philosophy of that particular species of late '80s to early '90s sales culture: "Get them to sign on the line which is dotted!" When Baldwin exits after his "Always Be Closing" scene, he nearly takes the movie with him. Yet Blake's presence hovers over everything that comes after, since he represents the unseen "Mitch and Murray," who presumably own the business and bought the new Glengarry leads. "To you, they're gold, and you don't get them. Why? Giving them to you would just be throwing them away. They're for closers only."

Whatever the audience may think of Mamet's politics, and whatever they make of Glengarry Glen Ross' message, the scorching ten minutes featuring Alec Baldwin stands as one of the most brilliant setups of any modern movie. Blake exposes the desperation and bitterness of all these salesmen. Levene blames the leads, which Blake knocks down. He emasculates Moss and berates Aaronow. We think we know exactly where everyone stands by the end of the scene, but even this level of knowledge is another con.

That last point seems to be the company's go-to strategy. Blake reveals that month's sales contest: first prize is a new Cadillac, second prize is a set of steak knives, and third prize is: you're fired. The bottom two salesmen will be cut from the roster, heightening the desperation of an already tightly-wound group of people. The stakes are clear and harrowing... but who is Blake, really? He has all the trappings of an extremely successful man, but he won't even give his name to the sales team he's there to motivate. Baldwin's clear relish in chowing down on Mamet's dialogue and his withering disdain for everyone he sees sells the speech so completely that we don't blame Levene, Moss, and Aaronow for buying this first level con. Their leads are garbage. Mitch and Murray don't want them anymore. Could Blake really make himself $15,000 in two hours with their material? Doubtful.

In 'Glengarry Glen Ross,' Moss' Routine Is Just Another Con

As Baldwin exits the story, Aaronow and Moss lick their wounded egos. The two characters enter one of the film's most intriguing sequences. Moss consoles the frightened Aaronow in his own not-exactly-sympathetic way. They have no support from management and their current crop of leads is full of "deadbeats" who can't afford the parcels of land in the first place. Moss places the blame squarely on the never-seen Mitch and Murray. It is Moss who pauses his diatribe for a misty recollection of when they were selling Glen Ross Farms, which apparently sold and sold until Mitch and Murray "killed the goose," whatever that means.

Having just watched Blake run the three salesmen through a verbal meat grinder, we can see how Aaronow could be primed for the type of scheme Moss has in mind. Framing it as payback, Moss suggests that someone steal the Glengarry leads. Aghast, Aaronow questions Moss, who gradually reveals that not only is he planning on stealing the leads and selling them to a competitor named Jerry Graff, Moss wants Aaronow to perform the break-in. Moss' idea was never some kind of spontaneous act of workingman's reciprocity. He had planned this far enough in advance to be ready with an offer in place from Graff when the Glengarry leads arrived.

Moss goes even further, talking Aaronow into a corner. Now that he knows what the scam is, Aaronow is on the hook as "an accessory before the fact." Never mind that poor, milquetoast George is horrified once he hears the full scam and inititally refuses. There is a parallel here to how Mitch and Murray have cornered their salesmen: Aaronow and the rest of the salesmen are left with little choice but to jump through the company's hoops, even with the writing on the wall. Moss' friend-of-the-working-man routine is just another con.

After the Break-In, the Cons Only Continue

Act two of the play and act three of the film follow essentially the same path: the aftermath of the burglary the next morning. Ricky Roma arrives to find windows smashed, the office a wreck, and the Glengarry leads long gone. A rude cop camps out in Williamson's office, ready to mercilessly interrogate every salesman. Roma should be over the top and demands his Cadillac after closing James Lingk the night before, extenuating circumstances be damned. Levene bursts in, crowing about an $80,000 sale from that very morning. We discover here the sour relationship between Moss and Roma, which turns spiteful after Roma reminds Moss "you haven't closed a good one in a month." Moss explodes and storms out.

This leaves Levene and Roma as Aaronow (who may or may not have stolen the leads) heads into Williamson's office for a grilling. Shelley "The Machine" Levine, who once ruled the roost there at Premiere Properties, recounts that morning's sale to Roma. Played out mostly in one long take as the camera dollies slowly away, Pacino provides a master class in reaction as Lemmon relishes what amounts to Levene's one final big sale. As he wraps up, Roma notices with alarm that James Lingk has found his office. What follows is essentially one elaborate con.

Lingk, after a haranguing from his wife, wants to cancel the sale. Roma's plan: stall. The two old pro salesmen engage in a extended bit of detailed deception, pretending Levene is a client as they talk circles around Lingk until Roma can calm him down. The plan appears to be working until Williamson blows the whole thing by assuring Lingk that his contract went out, and his check has been cashed. Roma is furious, and eviscerates Williamson in a particularly withering monologue. Yet this is not the film's final con.

Underneath 'Glengarry Glen Ross' Cons Lies Toxic Confidence

Levene appears, puffed up from his big sale and lectures Williamson about making up the part about Lingk's contract. This gives him away as the burglar, since Williamson really did invent the story about the contract; in fact, all the contracts were stolen. Suddenly cornered, Levene desperately attempts to negotiate, fingering Moss and pulling out the $2,500 he got for stealing the leads. He promises a percentage of his future commission, and when Williamson scoffs, Levene points to that morning's sale.

Here the final, overarching con reveals itself. Williamson tells Levene that the couple he closed, the Nyborgs, are "nuts." Their check is worthless. How does Williamson know? He called the bank when the lead came in. He knew their name from his previous company. Levene saw how they were living, after all. Williamson gave Shelley the lead, knowing it was a dead end. And why? Because Williamson doesn't like him.

This is the final con, and Mamet's last example of how confidence really works in the world of his stories. Like in House of Games, Shelley put his confidence in Williamson, and this has backfired. As Roma pointed out in his diatribe to Williamson, the office manager is there, "to help us, not to f@ck us up!" Levene should have been able to count on a level playing field when it came to the leads, even if they're old. Yet Williamson has targeted him from seemingly the beginning of his tenure at the office, for personal reasons. Mamet may or may not have intended this as a metaphor for capitalism, but it works as one just the same. There is no level playing field, at least not when our fate is tied up in a toxic interplay of confidence. Glengarry Glen Ross lays bare a strain of desperate anxiety in the psyche of the American working class. We suspect we're always being conned, and sometimes our paranoia is justified.