I’ve heard the argument that watching a Godzilla movie for the characters is like watching pornography for…well, the characters. Godzilla and its ilk are supposed to be destruction porn where kaiju punch each other, rassle, and anytime you focus on the human characters, you’re taking us away from the feature attraction. If you want to watch a movie about human characters dealing with human emotions, there are no shortage of those, but let us have our monsters beating the living daylights out of each other and crushing buildings. People in a Godzilla movie should be no more than facilitating the entrance of monsters.

I disagree with that argument and having sat with the Showa-era Godzilla movies over the past several weeks, one of the recurring elements I’ve noticed is how much the human characters can bring to the overall film. Even if it’s something as simple as the escape plots in Ebirah, Horror of the Deep, the conflict with the Xiliens in Invasion of Astro-Monster, or the weirdness of the Infant Island twins in Mothra vs. Godzilla, these non-kaiju characters aren’t simply lubricant for the plot. They ultimately represent the stakes and our entry into this world because the monsters don’t talk or tend to have any desire beyond “stomp this town” or “hit this other monster.”

Humanity in 2014's Godzilla

When you don’t care about the human characters, you get a film like 2014’s Godzilla. To be fair, there’s a lot to like about Gareth Edwards’ blockbuster, and I would argue that the film is a success despite some glaring flaws. And when it comes to the monsters, Edwards succeeds because he’s able to craft character onto them to the point where the two MUTOs have more romantic chemistry than Ford Brody (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) and his wife (Elizabeth Olsen).

But where 2014’s Godzilla stumbles badly is in its treatment of Ford’s father, Joe (Bryan Cranston). For those who haven’t seen the movie (or need a refresher), the film contains a prologue where a monster breaks loose from the Philippines in 1999 and heads to feed on a nuclear power plant in Japan run by Joe. In the attack, Joe loses his wife (Oscar-winning actress Juliette Binoche, who I hope was paid well for doing nothing in this movie other than dying) and spends the next fifteen years trying to figure out what caused her death. His son Ford thinks his dad is nuts, but through the first act of the film, they realize that Joe is onto something with his readings, and during an investigation at the ruined power plant, a MUTO (Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organism) arises and causes devastation. Joe is critically injured in the attack and dies at the end of the first act. Ford then becomes the protagonist of the remainder of the film as he goes from place to place and monsters keep showing up, which forces him to do hero stuff.

Human Characters Matter, Even When Giant Monsters Are Fighting

Let’s set aside the fact that Ford is a dull, uninteresting character and Taylor-Johnson, who has shown with his performances in Nocturnal Animals and Outlaw King that he doesn’t mind going wild when given the opportunity, doesn’t do anything with this character. The main problem is that the film failed to realize that Joe, not Ford, is its protagonist. By building the prologue around Joe and his personal loss, we’ve created personal stakes for Joe and how he is haunted by the events caused by these monsters. Instead, the film decides he should simply be a repository for exposition, the reason for introducing Ford (we never even get a scene showing how the loss of his mother affected him, so the prologue is all about Joe), and then wants a “twist” by killing Joe at the end of the first act with some vague instruction that Ford should care about his family even though we’re never given any indication that Ford is a bad father or husband.

The purpose of killing Joe is to try and up the stakes by showing that any character could be killed off by the destruction of these monsters, but it’s false foreshadowing and provides an artificial sense of danger since no other major character dies for the remainder of the movie. Joe is the only one who dies, so while it’s shocking in the moment and makes you wonder if another major character will perish, there’s no payoff, so the film has sacrificed its best character for nothing. Ford has no personal stakes other than being a good soldier who keeps surviving monster attacks, and he wants to get back to his family, which is about as general as a character plotline as you can get.

It’s to Edwards’ credit that he’s able to keep the movie afloat by teasing Godzilla and knocking the monster fights out of the park, but his film also has fallen prey to a key misconception about these movies, which is that characters don’t matter. The thinking goes that when someone pays for a ticket to a Godzilla movie, they’re not paying to see Bryan Cranston. Bryan Cranston is there because he’s a good actor, and he’ll do a good job selling the film when it’s time to promote it. But that’s a severe waste of what he and the stacked cast (which also includes fellow Oscar-nominees Ken Watanabe, Sally Hawkins, and David Strathairn) can give you, and more importantly, what any human character adds to these movies.

2014's Godzilla Can't Match 1954's Godzilla

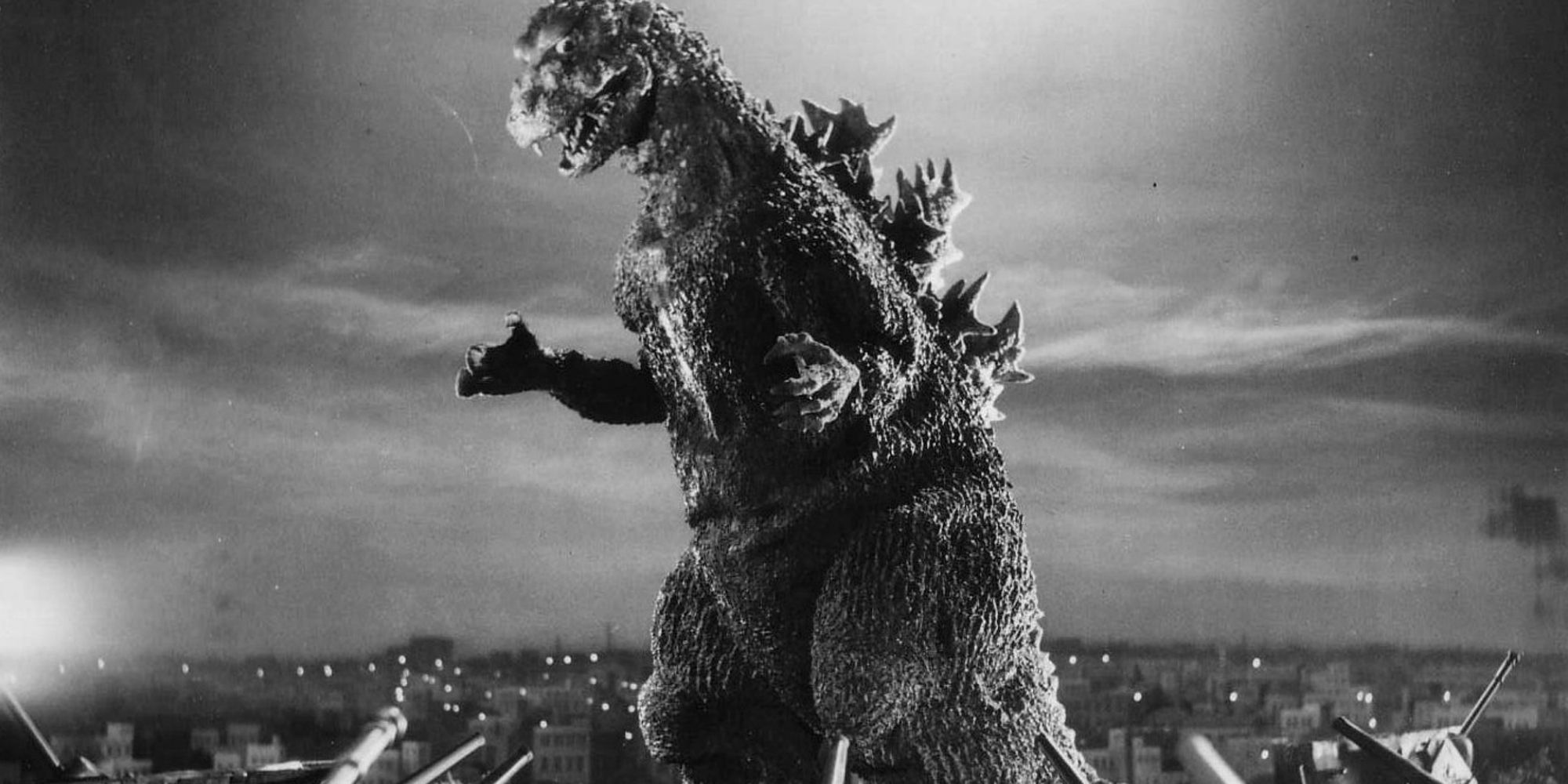

The reason that 1954’s Godzilla remains arguably the best film in the franchise it started is because it invests the human characters with pathos. Godzilla is a potent metaphor for nuclear annihilation, but it thrives due to the moral conundrum of the tragic Dr. Diasuke Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), a man who has created a powerful weapon that can destroy Godzilla but could create a new threat to humanity. Serizawa and his fellow characters are not simply there to facilitate the movie getting back to destruction but to wrestle with whether it’s necessary to deploy a new weapon if it means defense against a current threat.

Granted, sequels to 1954’s Godzilla moved away from the heavy drama of the original and into lighter fare, but the better entries understand that people are what keep the story moving and make us invested in what’s happening beyond the monster. Even a film as recent as 2016’s Shin Godzilla shows that the real monster may not be Godzilla but an impenetrable bureaucracy of well-meaning people who simply aren’t nimble enough to deal with a quickly evolving threat. In the movies where characters are an afterthought rather than the focus that a Godzilla movie suffers because ultimately you can only do so much with a hulking reptilian who stomps, punches, and has atomic breath.

Godzilla, as I’ve previously explained, is a potent symbol and a malleable one that allows different filmmakers to use him in interesting ways. But to make for a good overall Godzilla movie, you need to have characters worth caring about. And when you do have one of those characters, it’s wise not to kill him off 40 minutes into the movie.