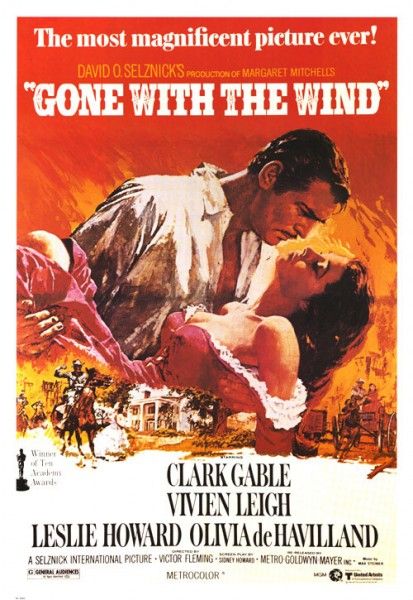

During quarantine, I kicked off my sheltering in place by watching the critically acclaimed Netflix original docuseries Tiger King. I finished the series in three days. Now where in the World will I find a cast of characters to quench my thirst for the same level of white ratcheted ignorance that Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin brought to the screen? I found them in the pages of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind.

Before the murders of Ahmed Aubery and George Floyd, before the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, and before the controversy about whether HBO should air a 1939 Academy Award winning film,one of my sisters, an African-American literature professor, suggested we start a sister-to-sister mini-book club. “What do you have on your shelf?” she asked.

You should know that over five years ago, my sister purchased a semi-vintage version of Mitchell’s novel for me as a gift, but I never felt compelled to read it. This book was part of the modest collection of classics I dusted off once a week. I’m known for inspiring rereads of authors like Dickens, Melville, Austen and contemporary favorites Morrison, Toole, and Octavia Butler.

I admit as a Black woman, I wasn’t itching to read a thousand plus pages of a saga that has slaves in it. I had seen enough clips of the film to be familiar enough with the story. But my sister’s question prompted “gift guilt” and a bit of quarantine wonder. So just coming off the heels of reading Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, I was ready to venture back into time, this go around on U.S. soil. “Okay, we gotta read it together and follow it up with Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone,” she insisted. “Okay, bet.”

Unenthusiastically, I cracked it open. Fifty pages in, I called my sister, “What in the Honey Boo Boo is going on with these white people in Georgia?” We exchanged laughs via phone like two cackling hens, discussing the shallow natures of Scarlett O’Hara and The Tarleton Twins. Our commentary was reminiscent of someone recapping a guilty pleasure reality show or soap opera.

I found it fascinating how certain slaves had parental-like control over both the master’s children and all the adult family members they served. (I am thinking of the relationship between Mammy and Scarlett). I’m sure seeing outspoken slaves that were “feared,” even for comic relief, by their White owners, wasn’t the part of the narrative that Hollywood intended, especially in 1939, during the height of the Jim Crow laws.

Mitchell reserved the N-word for frequent use between black people. However, white characters referred to their slaves as “darkies,” which was particularly unsettling for me. After reading the word “darkies” one too many times, I had to put the book down and find out who the hell is this Margaret Mitchell?

Those two sentences from her bio told me everything I needed to know. It also added context.

Scarlett’s treatment of Prissy was textbook master/slave relations and the primary reason why this book remained unopened on my shelf for so long. The footage of Ahmed Aubery being savagely murdered in Georgia was released the same time I reached the chapter where Atlanta is under siege and Scarlett is escaping to Tara. The feeling of watching a movie on an airplane about a plane crash, while the plane is actually crashing, engulfed me. And again I asked, “What is going on with these white people in Georgia?” Aubery’s death added an intensity to the reading I could not comprehend. It was also confirmation that although this was a ‘period’ piece, not much has changed.

A friend asked, “Why are you reading that racist-assed book?” Gone With The Wind sparks extreme emotions in people. When they heard I was reading it, an associate told me it was his mother’s favorite book and she used to read passages to him and his sister when they were little. The thought of this conjured up all types of feelings and questions: Did your mother explain what a “darkie” was? Did she tell you that it was a derogatory term that you should not use? Did she simply avoid those parts of the novel? Or worst of all, was she grooming you to be racist? The thought and image of a WASP-y mom doing an impression of Mammy for her seven year-old makes me cringe. I cannot deny that Gone With the Wind is a beautifully written novel. However, the subject matter is not something Iwould introduce young children to.

I personally believe that this material is not appropriate for adults who romanticize the antebellum South or, like the author, have an idealistic conviction rooted in a delusion that the Confederate Army won the Civil War. Speaking of delusional convictions, it was always implied (never formally affirmed) by my education in central New York that not only did the Union win the war, but they also freed slaves and were for the equal rights of Black people. Somehow, my history lessons never quite explained how the Emancipation Proclamation did not obliterate racism. Nor did any teachers or textbooks excuse or deny the system that continued to benefit white people.

“Do you think I’d trust my babies to a black n****? I want a good Irish girl.” This line spoken by a Yankee woman (the period piece Karen), when Scarlett suggests finding a negroe nanny, highlights the point and pain of white privilege even after “change” (in this case Reconstruction). Scarlett’s indignation that this woman used the N-word in front of Uncle Peter, a house negro who was chauffering Scarlett around, infuriated me. This is the same character who used the word “darkie” freely and was unapologetically going upside Prissy’s head. In this moment of blatant racism, she elevates herself above the Yankee woman who was not dignified enough to address Black people with respect and later detailed the “proper way” of dealing with Black people was to “tenderly” treat them “like children” as had been so instructed by her mother Ellen O’Hara. Later, this Uncle Peter “ally,”complained about free Black people laughing in the streets or having positions in local government that their sheer color disqualified them for.

Revisiting Mitchell’s narrative of the Confederacy and The Union, just like reviews of the work and mission of Malcolm, Martin, or the policies of the Democrats and Republicans, reveal the unfortunate truth — that at the end of the day The South was no more racist than the North. The racism is merely manifested differently.

Scarlett’s comfort with “respectable” Black people, like Mammy and Pork, who still are imprisoned by boss/servant power structures, is eerily reminiscent of the “performative progress” that this system has offered me as an educated Black woman. Over the years, I have been thrown “entry-level-sized” bones of achievement, where my white peers have been given steak in the form of doubled pay and opportunity.

To her dismay, Scarlett’s disdain for “uppity” educated Black people, may perhaps be Mitchell’s beautiful mistake of showcasing Scarlett’s insecurity. Her fear of losing her lumber business if she expressed this disdain during Reconstruction was insightful. Covert behaviors like those of Scarlett O’Hara’s toward free Black people, today, is labeled micro-aggressions. Or as I like to call it, good ‘ole aggression. I cannot tell you how many times I have been subjugated to this kind of insecurity. I have witnessed numerous workplace blocks and obstacles fueled by whispered sentiments of inadequacy at the thought of my or another Black person’s opportunity for advancement. The saddest part is many of these blocks come not in words, but in attitudes and deeds.

Mitchell’s ode to the Confederacy is blatantly racist. Reading the anti-Yankee rhetoric reflected in the pages of this novel is a haunting truth I am not sure I was ready to contend with. There are no “good guys on both sides,” as we have been told. Black people, then and now, seem to be pawns in the battle between the North and the South, Left and Right Wing. With each unarmed death, as in each page read, increasingly confirmed that our true freedom or liberation is of no genuine concern. The Gone With The Wind narrative, along with the accolades it has received, makes for a perfect American metaphor.

After reading the novel, I watched the film in its entirety. I know adaptations never do the novel justice. Still I found it interesting what details Hollywood chose to omit. Gone was Scarlett O’hara’s frequest use of the word “darkies” and the fact that she had not just one, not two, but three baby daddies. The film version preferred their maiden with a singular father, and much fewer “darkies.” But just as I am ready to thank Hollywood, I, like Hattie McDaniel, am silenced by the Academy (it’s said the movie studio wrote Hattie McDaniel’s Academy Award acceptance speech).

“...it’s important to have context whenever you’re viewing material of this kind. Otherwise, people can embrace and celebrate it without dealing with the whole truth.”

- Todd Boyd, USC Professor of Media

I agree we cannot turn away from these stories. HBO placing Gone With The Wind back on the HBO Max service was the responsible thing to do. Erasing this film does not eliminate the truth of its existence. It only leaves us without witness to the brilliance of actresses Hattie McDaniel, Butterfly McQueen, and the other talented Black performers who endured only God knows what to express the beauty of their artistry amid degradingly reductive roles.

I am anxious to read Randall’s Wind Done Gone, a historical novel which tells the story of Mammy’s daughter. The idea of another perspective of the antebellum South, where Black womanhood is explored is a necessary part of my healing right about now. I am secretly praying that Ava DuVernay is somewhere reading Randall and having screen adaptation dreams, as I am.