Achieving mediocrity can be seen by rejecting the superficiality of the world and denouncing traditional notions of what it means to be successful — whether it be a high-paying job, fancy furniture, or creating a perfect, nuclear family. Mediocrity can also be in the everyday, mundane parts of life that allow individuals to be in the moment — where higher goals and possessions should not matter to their overall happiness. Mediocrity takes the specialness out of life or a person, where they exist, not how they should be.

Mediocrity in film has been explored in numerous dynamic ways: from nihilistic mindsets to understanding that achieving perfection is futile, seeing life from different viewpoints, and changing lifestyles for a new outcome. Existentialism makes for the best films - because they provide escapism or question life choices in the eyes of the beholder.

'Taxi Driver' (1976)

Directed by Martin Scorsese, Taxi Driver is an American drama set in a crime-filled, morally corrupt New York not too long after the Vietnam War. The protagonist, Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), is a young war veteran who has PTSD and insomnia and begins a career as a taxi driver on night shifts in an attempt to cope. Working as a taxi driver, he meets campaign volunteer Betsy (Cybill Shepard) but ruins their relationship and begins to fantasize about a city where there’s no crime. This fantasy scopes deeper when he regularly encounters child prostitute Iris (Jodie Foster) and makes it his mission to save her from the streets.

Taxi Driver ends with a disclaimer on screen: “In the aftermath of violence, the distinction between hero and villain is sometimes a matter of interpretation or misinterpretation of facts. ‘Taxi Driver’ suggests that tragic errors can be made”. The film interprets escaping from a mediocre life by becoming a hero — where Travis’s motives are selfless. After living a life where he wants to conform (in the sense of feeling less alone) but not having the ability to do so, his fantasies consume him. His mediocre life comes from feeling unfulfilled — he went from a war hero to a traumatized person who lacks substance in his life, overcome by insomnia. Travis chooses to fight mediocrity with (albeit misguided) heroism — and becomes an anti-hero in the end.

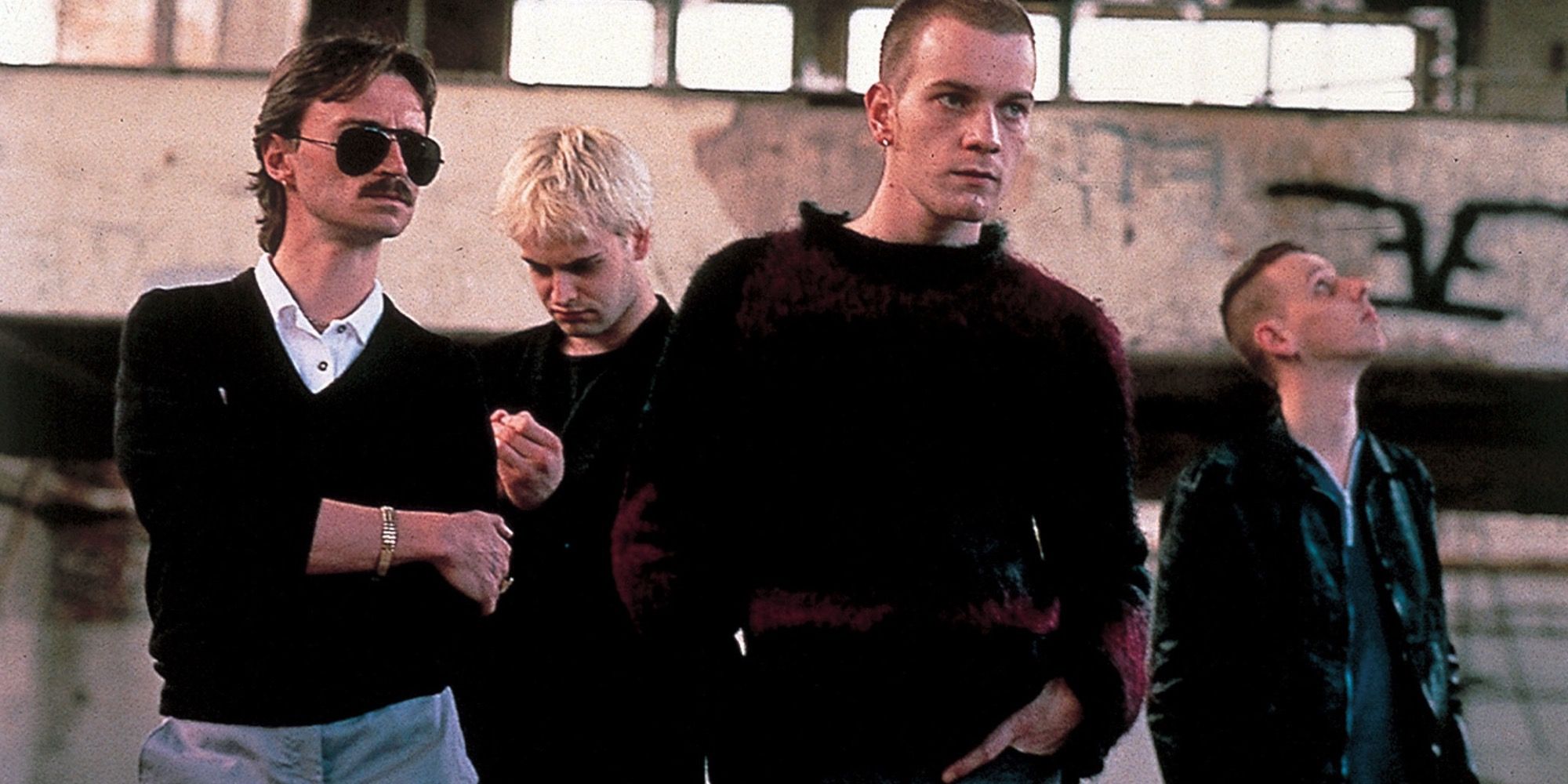

'Trainspotting' (1996)

Trainspotting is a drug-fuelled comedy-drama with the ever original Danny Boyle, following Mark Renton (Ewan McGregor) through his heroin use and attempts at rehabilitation, where he is dragged down by friends Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), Spud (Ewen Bremner), Swanney (Peter Mullan), Begbie (Robert Carlyle), and Tommy (Kevin McKidd). As Renton begins a relationship with an underage girl Diane, he is forced into staying with her in fear she’ll report him to the police. When he finally gets clean, he struggles with a loss of purpose, resulting in poor decision-making.

The drug use in Trainspotting has led to a mediocre life - the repetitive nature of buying and using drugs becomes too mundane for Renton, yet he cannot figure out how to navigate life without it. “Who needs a reason when you’ve got heroin” is quoted in the film, reinforcing Renton’s anti-materialism, anti-"rat race" stance that he claims is the collective societal reason to live. Renton acknowledges that no one chooses life; they receive retribution for all wrongdoings but never redeem themselves. Living in a world bitter by social class rankings, violence becomes the change that makes morality irrelevant — a surrealist opinion that comes about with a life of mediocrity.

'Fight Club' (1999)

Embracing mediocrity is the center of the cult-classic drama Fight Club. Directed by David Fincher and adapted from the novel of the same name by Chuck Palahniuk, an unnamed and unreliable protagonist (Edward Norton) leads viewers through his struggle with insomnia, his alignment with his goals, and his identity. He goes to self-help groups to find solace because other people have it worse than himself but finds himself polarized by Marla (Helena Bonham Carter) — a woman who does the same. On a work trip, he meets Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), a confident, well-dressed man who wishes to enjoy the freedom of irresponsibility. They soon begin a "fight club": an underground organization where men can throw punches at each other to expel their dissatisfaction with their mundane lives.

Nihilistic tones rule the film, whereby Fight Club attempts to strip back its characters into a sameness — they conform to non-conformity by believing that no one is special. Instead, they are the “same decaying organic matter as everything else,” where everyone is “part of the same compost heap." By embracing mediocrity, Fight Club tears down the capitalistic, materialistic lifestyle that creates class division and forces individuals to want more than what they have. In addition, society overpromising success and fortune to its people leads to a jaded, disaffected populace itching to rebel.

'Office Space' (1999)

A satirical look at the working life, Office Space is a comedy-romance that sees the everyday white-collar man fight back against mediocrity. Peter Gibbons (Ron Livingston) is an unmotivated member of a tech company who, along with co-workers Samir (Ajay Naidu) and Michael (David Herman), become tired of being treated poorly. Constantly fearing they’ll lose their jobs but dissatisfied with problematic office rituals, the group decides to get revenge by embezzling money. After Peter feels enlightenment post-hypnosis, he changes to a carefree attitude, allowing himself the pleasure to do as he pleases — which seems to be the moral of the film (in a comedic way).

Stifling work cultures and ever-present issues with the main character’s true desires, Office Space explores the lack of fulfillment in daily life, where the comfort of a situation no longer becomes an adequate excuse to allow it to exist. By simply becoming the person Peter wanted to be, the film promotes the simplistic approach to happiness: removing things from life that make one unhappy. The existentialism in Office Space ties in with mediocrity because work-life has encapsulated all meaning into a 9 - 5 grind — a concept that many viewers can empathize with. The film fights mediocrity with mediocrity, whereby a change in attitude does not radically change the protagonist’s way of life or how he lives it.

'Gattaca' (1997)

The science-fiction film Gattaca draws important conclusions about issues of perfectionism, genetic modifications, and the idea of destiny in a cold, mundane dystopian setting. Vincent Freeman (Ethan Hawke) is ascribed to society as an "invalid": an individual conceived naturally and susceptible to genetic disorders. His position in society devalues his skills, where he is confined to menial work while he dreams of traveling to space. Vincent gets a chance to pose as a valid and work for Gattaca Aerospace when he meets Jerome Morrow (Jude Law), a disabled former swimmer who gives him his DNA so that he can live out his dream.

Gattaca explores living in a world where one is forced to live a mediocre life dictated through genetic sequencing. Vincent fights to live in a world he is discriminated against, where he proves to himself that despite his health status, he can achieve his goal regardless. Despite the odds, Vincent rebels against his mundane cleaning job and turns into an astronaut. The film also explores mediocrity as something that can be positive.

Though Jerome’s perfect genetic code enabled him to perform his dreams, his life changes when he is paralyzed in a car accident — where being perfect no longer serves a purpose. Bitter, Jerome hates the world he was created in, as he realizes that he could not reach the perfection he wanted in life despite being genetically perfect. Attempting suicide, Jerome found it easier to live without the pressures of perfectionism, and helping Vincent achieve his dream made him realize that the world they live in set out to fail them both. Being destined for mediocrity doesn’t seem like an ideal life, but neither does not have a choice to live through it.