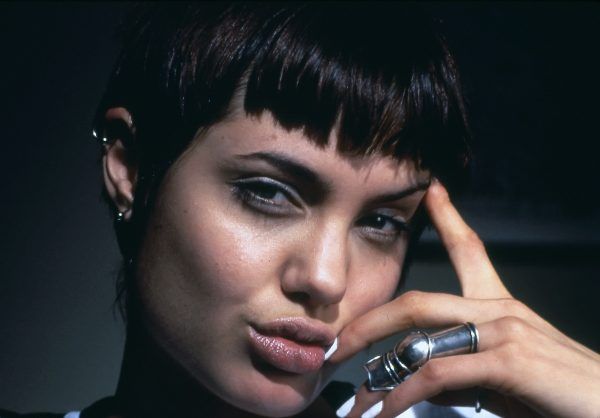

Goodness gracious, I love Hackers. Starring Jonny Lee Miller, Angelina Jolie, Fisher Stevens and more, the 1995 cyberpunk film about a group of rowdy hackers who fight against an oppressive technocratic state of being with the punk-rock power of, well, hacking. It's a blast to watch, a fiendishly entertaining, surprisingly subversive piece of elevated mainstream filmmaking. It's both incredibly campy and unabashedly sincere. It's full of delightful moments, wild performances, incredible production design, and an utterly bangin' soundtrack. If you're looking for a good time with nutrients at its core, look no further than Hackers.

In honor of the film's 25th anniversary — and the bangin' special edition soundtrack just released on vinyl from Varèse Sarabande Records — I was lucky enough to speak with the director Iain Softley over Zoom for 45 friggin' minutes. We got into the film's exploration of counterculture, the influence it's had on the tech industry since, the joys of discovering one Angelina Jolie, the intentions behind the dancefloor-ready soundtrack, the strange way it influenced Christopher Nolan, and much, much more. Enjoy, and as always: Hack the Planet!

Collider: Do you remember the first time you heard about hacking as a concept?

IAIN SOFTLEY: I think it must have been before I read the script. But really, it was sort of quite a distant knowledge — people hacking into computers, hacking into mainframes. But I sort of knew that there was a kind of a, what we would now call a digital underground. But I didn't really know what form it took, how extensive it was, or who the people were that were doing it. This film was my education into the world.

And what did some of that education look like? Who were some of the hackers you talked to, what was some of the research you did?

SOFTLEY: Well, we sort of plunged right in, actually. And it was very broad and very varied. I started [research] the spring of 1994. But I don't think my first film, Backbeat, had been released yet. It had opened the Sundance Film Festival, so I sort of was coming [and] going straight from one to the other. And immediately I noticed the counterculture element potential in this script. And that's something that I wanted to emphasize. So that motivated me in terms of the sort of people and the sort of places that I was looking for. [Counterculture] influenced the research, and the more I looked, the more I found that the counterculture — people working in music, graphics, clubs, clothes — was actually already really bubbling under the ground. So I was lucky in the timing of it, in that sense. Because people hadn't been exposed to it, weren't aware of it, and it actually, particularly in hindsight, made the film look as though it was really anticipating a wave that was about to break.

So the first protocol, really, was the script by the screenwriter Rafael Moreu, who'd done a lot of research with some of the prominent people in the hacking community in New York, [including] the 2600 magazine run by a guy called Emmanuel Goldstein. And there was a group around him, and there were other people that Rafael had spoken to, who sort of became advisors on the film. And when we were cast, we went with the cast to New York and had a sort of hackers' boot camp for about three weeks before we started shooting. So they hung out with a lot of these guys. But we went further than that, and sort of branched off to the side.

There were clubs in London, like a club called Heaven, which had a sort of cyberpunk night. And there were clubs in New York, specifically a club called Save the Robots, which was a very underground club [and] had a kind of cyberpunk-type name to it. And there were nights in different places which were starting to play more dance music. The acid house scene had really kicked off in the U.K. in the late '80s and developed into the outdoor rave scene, and then sort of became more [prominent] with established super clubs. And that was really a very, very current thing in the U.K., and I was starting to see that in the U.S. as well, but not in any way nearly as pervasive. But certainly the way people were dressing — we took the queue from the people that we were seeing in clubs in the costume design. But [costume designer] Roger Burton took it a stage further, really pushed it.

But we were working with a guy called Neville Brody, who was a cutting edge graphic artist — he did designs for a very current, hip magazine called The Face in London. And so the idea of designing interfaces and screensavers and things like that, nobody was talking about that, commercially, or the general public had no knowledge of it. But Neville was already at that stage. I talked to him about this idea of trying to make [cyberspace] this world that the characters disappeared into. And so we were, in a way, presenting physically something that was like a projection of what was inside their head. The technological hallucinatory element to the film, and the visualization, was something that very much evolved in the research.

And then, even when we talked to people at MIT, or people in San Francisco, we were picking up that there was a kind of counterculture environment in which [the tech industry boom] was happening. A lot of the people in San Francisco, particularly, very much saw the link with psychedelia and flower power, and the ideas for how the world would exist without borders, and it would be a world where the old order wouldn't be so much in control. So that kind of counterculture thing was very much around. And it was actually very exciting and stimulating, because the more we delved, the more we got back things that were useful for us to put into the film.

It's interesting to me, I think especially with cyberpunk and counterculture, there's kind of a philosophical worry of society backsliding into a corporate dystopia, exacerbated by technology. And yet, to make a movie with MGM, a wide release movie, there is inherently a bit of corporatization, commodification of something that maybe is designed not to be. How did you reconcile or deal with that?

SOFTLEY: I think that that's happened in movies all along, whether it's A Clockwork Orange or Bonnie and Clyde. I mean, certainly even the movies in the '70s, there was always a kind of a sense that studios, in certain instances, were allowing people to make films that would be provocative to a mainstream audience. In fact, the head of United Artists, which was the sister studio to MGM, had just sort of been revived under the stewardship of a guy called John Calley, who had been in retirement and he'd come back. In his previous incarnation, he was the executive credited with Catch-22 [and] commissioning Stanley Kubrick's films. So [countercultural films are] sort of what he wanted, and that's what he liked about Backbeat. He saw Backbeat as quite a bold, counterculture film. And it was made by Palace Pictures, an independent filmmaking company in the U.K. who sort of thrived on making films that were provocative. And it was released by Polygram in the U.S., which was a record company.

And I didn't realize at the time the freedom that I'd been given. I think that what John Calley wanted to do, and Jeff Kleeman, who was the executive who worked with him, they were both very, very supportive because they were big fans of Backbeat. And they didn't want to clip my wings. They wanted to facilitate and allow me to channel. They didn't want to restrict any of my ideas, because what they were after was the ideas that they were seeing in Backbeat. I mean, [Hackers] was probably the most freedom I've ever had in making a movie, because it was off the back of [Backbeat], that at the time that they approached me, had just been in Sundance. I think the planets aligned for me there. So I didn't really think about that irony. I'm sure that there were people in the hacking community who might have.

But I think what's happened subsequently is that people were very, and I've been told this because a lot of the fan base was teenagers and people in their 20s, who weren't really being catered for in movies very much. Certainly not the mid-teens, the 15, 16-year-olds. Whereas these days, you have the franchises, Harry Potter, Twilight, Hunger Games, which are very much for young adults. A lot of the people that saw the film at that time, they associated with it as a film that really spoke to them. And a lot of people that are in their 30s now, who are in tech, in quite elevated positions in tech, they cite the fact that Hackers was a film that they really thought was speaking to them. But also they feel very protective of it, in a way. I've been to festivals and things, where I've screened Hackers, and these [people] are in the audience, and even though they're now in quite senior positions in tech companies, a lot of them are dressed like cyberpunks. [laughter] Only when they attend the screenings.

So this film, in being able to speak to teenagers, 13 through 15-year-olds, were there ever any issues in securing that PG-13 rating? Or was there ever a hard-R version of the film?

SOFTLEY: There was certainly a version — and in the U.K., that version would have been a 15, because there is this intermediary rating — there was more nudity, I think, and there was more "language," as they say. But it wasn't toned down a lot. One of the things I did with the script is that I sort of upped the sexuality of it, particularly in the relationship between Jonny and Angie [Angelina Jolie].

I imagine it was a kind of a "planets aligning" moment finding Angelina Jolie. This is, I would say, one of her breakout roles.

SOFTLEY: It was. Well, she calls it her first role. That's how she describes it. Certainly her first lead role. I met her at the Berlin Film Festival a few years ago, when she was premiering one of her films, and she introduced me to the cast who were there as the person who gave her her first film and her first husband. [laughter]

So again, it was the confidence and the support that I was given by John Calley and Jeff Kleeman. I worked with Dianne Crittenden, who was the casting director on Backbeat, and she was looking for people in Los Angeles and New York. And I had a casting director, Michelle Guish, in London. And we looked in those three cities. And Jonny Lee Miller, obviously, was my choice in London. And I'd seen people, and got a really interesting shortlist of both male and female actors from my casting sessions in New York and LA. And so what I did was a sort of final callback session in New York, and we flew Jonny over and paired him, and a couple of the other front runner male performers, with the front runner women. And I actually found the DVD of that casting about five years ago; I think it coincided with the 20th anniversary release of the film. And it's really interesting because there are some really good actresses, particularly. At least three of them have become major movie stars. They were all, like, 18-year-olds, so they were very, very young. And for all of them, it would have been their first kind of major film.

Can you say who some of these actors were?

SOFTLEY: No, it would be unfair. But it's interesting, because we laugh about it, and it sort of meant that we have a connection. So whenever I see them, it's kind of weird, because they didn't get the roles, but they sort of have fond memories of the experience. But in the scenes where Angie is with another actor, or Jonny is with another actress, they're great. But when you see them together, it's unbelievable, the electricity that just pops out of the screen.

In those days, and it wasn't just with John Calley and Jeff Kleeman and United Artists, it probably happened for my first three or four films, is that one went through a proper casting process. And people would come in and read, quite established people. And you would see who was most appropriate for the part, and then you would put them in combinations, and you would see who the people that really clicked and had that alchemy [were]. And what it meant was it was actually easier to cast actors that weren't necessarily huge movie stars, because if you could demonstrate on the casting tape, to the head of the studio, you say, "Look, what do you think of these people?" And they would often say, "Oh, who are they? You know, we can't fund the film with them. Are you sure there aren't any people with a longer resume, who are better known?" And then they would look at the tape and they'd go, "Oh my God they're amazing. You're right, let's go with it." So again, that was very, very lucky. And it wasn't just Angelina and Jonny. It was Wendell Pierce, who went on to great acclaim in The Wire. Lorraine Bracco, of course. Fisher Stevens. Matthew Lillard, who popped in Scream soon after. Jesse Bradford, great actor. And weirdly, Jesse was probably, of the group, the one that had the most experience. He'd been in a [Steven] Soderbergh film [King of the Hill]. I didn't really have any doubt about them at all, the cast.

And we put them together almost like a band. The experience I had of rehearsing the actors who played the band in Backbeat, which is about the early days of the Beatles in Hamburg, was [that] the actors hung out as if they were in a band, and they played together. So I sort of did the same with Hackers. I wanted them to be like a group. Because part of the idea was [that] this was the next rock and roll. So we gave them laptops with guitar straps. But what it meant was that particularly the smaller roles, even though it was kind of an ensemble, particularly Laurence Mason who played Lord Nikon and Renoly Santiago who played Phantom Phreak, they made their characters so much bigger in the performance than they were on the page. I think that was true for all of the actors, but those guys in particular, because their parts were kind of smaller, were really punching above their weight.

I wanted to touch on Fisher Stevens' performance specifically. To me, when I watch the film, he feels so much, down to his beard, like literally the devil. What was some of the inspiration for his performance style in that film?

SOFTLEY: Well, he saw himself as this gothic sort of villain, outlaw, almost like a gunslinger. He'd made a lot of money working as the head of security for this huge oil company. Because that was what was on offer to [real hackers], you know. They could turn from outlaws to employees and be given huge salaries. So he had sort of taken the devil's money, if you like, in terms of the story of the film. And so he was dressed like an Alice Cooper or something. But, in terms of his own character, he was just very stylishly kind of dark and edgy, and enjoying the kind of hedonism of his newfound wealth. And it was reflecting the arrogance that he had, that he thought he was the best, nobody could beat him, he could taken them all on, and nobody would discover, and nobody was smart enough. They were all too ignorant to realize he could run rings round his employers.

There's a scene with him later in the film: Jonny is holding up a floppy disk in this beautifully shadowy, steam-filled wide shot. Fisher skateboards in and grabs the floppy disk. If you were to stage that scene now, where floppy disks don't exist, would he be picking up a flash drive? How would you stage that scene right now?

SOFTLEY: Yeah, I think that's what it would be, it'd be a flash drive. There's a kind of parody element [in the film], because when there's the face-off with the rivalry and the competition between the Dade character and Acid Burn, Dade does this sort of scene from Taxi Driver, with the floppy disks as opposed to with the guns in front of the mirror. The thing is that Hackers is a comedy as well. And it sort of intentionally doesn't take itself seriously. But what emerges as it progresses is a very emotional story about friendship and the fact that you'll look out for your mates. So when one of them gets imprisoned, they're doing everything to get them out of prison. And they've been great rivals, and there's been a lot of bragging rights, and "I'm better than you," and a lot of joshing up to that point. And then they really come together as a group when there's an enemy that's defined. And they realize they're averting a potential environmental disaster. But up to that point, there's a lot of comedy, in terms of the way that they play.

And I think [technology is] one of the things that is dated in the film, because technology becomes obsolete, you know, every three months. But we never set out to make a technological film. We never set out to say, "Okay, this is an up-to-date film that's going to anticipate the technology." We were making a counterculture film, a cyberpunk counterculture film. And really what we were trying to anticipate and explore was the idea of what that counterculture could be and would look like. And as I said, we were working with people that were telling us what it was going to look like. And that was really exciting, to sort of be able to let our hair down in that way, in a way that wasn't really how that world was looking at the time.

To me, the "surfing through cyberspace" sequences, when we plow through data or computer machinery, feel tactile and real, and very timeless. What were some of the visual effects techniques in these sequences?

SOFTLEY: Well, that was sort of what I was saying, really, when I was trying to say the experience of it was what we were trying to go for. And I think that's not only not dated, I think that that has become more current now than it was, or recognized more no, and understood more now, than it was at the time. Because at the time, people thought, "Well everyone knows the internet's not going to be more than just text on a screen." But we knew, from the people we talked to, it wasn't going to be that. And again, I wanted to make it to be an expression of what it felt like, the excitement that they felt, what they were visualizing when they were going through something that you can't see; you know, it's data. And I specifically wanted that to be as exciting and as three-dimensional and as immersive as a cinematic experience as I could make it. So my inspiration for that was the sequence in Stanley Kubrick's 2001, when we approach the spinning space station. When I first saw that on 70 mm film, it was like I was in that space. And I thought, "I want us to feel that."

Like the rest of the film, it's shot on film. There was pressure, at one point, to do that visually with 3D design. But 3D design, it wouldn't look like that. 3D design would actually look two-dimensional. So I built a physical set, about 50 to 100 yards in a small studio, of these Perspex towers. And we used motion control, and we lit everything from underneath with those amazing colors. And we actually had animation cels that were moving all the time. And I just knew that was the only way that we could get it looking three-dimensional like a real, immersive world. It wasn't just this flat thing that only existed on the surface of a computer. It was like a technological trip you were going into.

And interestingly, the team that I put together, from lots of different companies, were cutting their teeth on this film, in terms of the visual effects. It was the first film that they'd done. And they all created a company after Hackers. And that is the company and team that Christopher Nolan uses for all his films. And interestingly, I'm in touch with them still, and they tell me that they use a lot of the techniques that we used on Hackers on the Nolan films. Because my idea, which, it's obviously his idea as well, is that you shoot as much stuff in the camera as you can. Because for a cinema audience, it's an immersive, inviting, beautiful world to exist in.

One element of counterculture that really shined through for me is the costume design. In particular, there's a lot of, to me, androgyny going on in it, and a lot of gender bending, especially with Angelina wearing performatively masculine clothes and Matthew Lillard wearing performatively feminine clothes. Was that an intentional sort of political point you were trying to make?

SOFTLEY: Yeah, exactly. And it was also an ethnically mixed cast for the time, that wasn't a sort of a "ghetto film," or a specifically Black or Puerto Rican film. It was actually difficult to make movies with ethnic minority leads at that time, unless it was seen as a film for a particular ethnic group. So it absolutely was a decision that — we wouldn't have called it "political" — but it was certainly a social kind of colorblind and gender-blind [decision], very, very intentionally. To the extent that we had Marc Anthony as a Puerto Rican Secret Service guy, and Wendell Pierce as a Black Secret Service chief.

In fact, Lord Nikon improvised this fantastic line, and just burst out laughing when he first saw the film because he had no idea I was going to [use it]; he was doing it as a joke. For the first time, Dade, the Jonny Lee Miller character, has to acknowledge why he can't be involved with them breaking into the computer mainframe of the oil company to try and find the virus. He's forbidden to go near a computer because he's got this criminal record, because he was Zero Cool. And Lord Nikon, because of his photographic memory, recites all of the things he did: He broke into 55,000 mainframes, hacked 200 banks, whatever. And then he stops and goes, "I thought you were Black, man." [laughter] That was the improvised line. And I kept it in, and he was like, "Ah, that's incredible, you kept it in."

But we also had some, I don't know whether you saw it, but in the school corridors, some of the guys are wearing kilts. And there's that whole gag about [Miller telling Jolie] "You go on the date, you wear a dress." And in fact, he wears this costume which is sort of like a dress, like a half coat, half dress. And the people laugh at that, because they see that actually he's wearing a dress on the date. And Roger was fantastic like that. Roger was very bold, very provocative. Really understood the potential. And we even had some, which I think was Roger's idea, we had some barcodes tattooed on people. And then of course, the whole dyed hair thing. It was not particularly prevalent at that time, you know, it was some time before Billie Eilish.

Did he also come up with Matthew Lillard's hairstyle in that film? That's such a unique look.

SOFTLEY: Liz Daxauer was the makeup artist working with Christine Blundell, and Christine Blundell is an Oscar-winning makeup and hair artist in the U.K. And interestingly, I think the Oscars that she's won have been for Mike Leigh films, which are very, as you know, [rooted in] social realism, and about as far away, aesthetically, from Hackers as you can get.

What was great was that people were really inspired once they realized I wanted people to really let their hair down, and to push everything. And we're talking about this on the 25th anniversary of the release of the film, but also in the run-up to the release of the soundtrack for Record Store Day. Everybody was aware of what music I was going to use — dance, house music. And so that kind of told them the sort of direction I was wanting to go in. Because that culture already had people wearing those kind of clothes, and had that kind of design palette in the locations, in the clubs. And everybody realized that there was really almost nothing that they could do that I would not embrace. And I showed people references and the direction I wanted to go, and it was just one of those occasions when everybody was very excited about the opportunity. And everybody got it. Everybody was moving in the same direction.

Speaking of the soundtrack, it really, from the jump, the very first cut, has such a big, bold, brash, EDM kind of sound. But we often see Jonny's character have a Nirvana poster in his room. And I'm curious if there was ever any other kind of musical palette pitched for this film. Was there ever a grunge version of it?

SOFTLEY: No, never. Right from the get go, I was convinced that this was the music. Because that was the world that we were in in London, and that was the world that was reflected and consistent with the costumes, the design, and the graphics on the computer, and what we were trying to say about the next step of counterculture.

It's interesting that you mention grunge, because the soundtrack for Backbeat was produced by Don Was, but the band that did the covers for the Beatles was what was called "The Grunge Supergroup." And they actually won a number of MTV Awards. So it was Dave Grohl on drums, who was in Nirvana at the time. Mike Mills from R.E.M. Thurston Moore, Sonic Youth. Greg Dulli, Afghan Whigs. Henry Rollins. It's an unbelievable band. So it did very well as a soundtrack with Virgin Records.

We had the same music supervisor for Hackers as we had for Backbeat, Bob Last. And so Bob arranged a screening in New York when we were shooting, and he was very excited. And then later he showed, when we'd finished the film, in Los Angeles, he had a screening for the finished film. And everybody said, "Nobody in America is going to listen to techno. We were expecting a grunge track for Hackers." And I said, "No that's not the film we're making. We're making a film that's a cyberpunk film. And it's about what's happening around the corner. And so it's a rave soundtrack." And so we didn't get a record release for the release of the film in the States. Which at the time was a big disappointment, because a soundtrack release, particularly for a film like this, was a big part of the marketing and the publicity.

But the film was released about five, six months later in the U.K., and I'd had another go at getting a soundtrack. And the the head of marketing for the U.K. distributor agreed that it would be a good idea. But it was quite a small release on a label called Edel. And we couldn't get permission, I think because there just wasn't time, for a number of the acts. And they were really kind of key songs. One of them was Leftfield's "Open Up," with John Lydon from the Sex Pistols on vocals. And the other was "Protection" [by] Massive Attack, which is a fantastic track. And Massive Attack [is an] amazing band to have on the album; they're now on the album. But also, most importantly: the climax of the film, in a way, is the Grand Central moment when they're in the spinning phone boxes. And there's a track by Guy Pratt, and he got an uncredited David Gilmour to play guitar. And it's the first time we've been able to credit David on it, and it's the first time we've actually had that track on the album. And on the internet, people are saying, "Why wasn't it on the album?" But nevertheless, that original album did very well. It went platinum in a couple of countries, to the extent that they released Hackers 2 and Hackers 3, which went further and further away from the real music of the movie, but certainly made a lot of people think, "Where was Hackers 2 and Hackers 3? Did I miss it? Where were those movies?"

So this is the first time it's on vinyl. It's a fantastic double vinyl. And there's a lot of artwork with photographs, and a fantastic appraisal of the film by a very prominent writer, a film critic in the U.K. called Mark Kermode, who's also a kind of big music guy and performs himself. This is an important and a special release for me. And I never thought I would see the release of the definitive soundtrack album, that actually has a comprehensive selection, and a representative selection, of the music in the film.

One of my favorite moments in the film is when the music explodes within the framework of the film itself, and we have this awesome live performance from Urban Dance Squad. What was the process of staging that and putting that in the film?

SOFTLEY: Well, it was always going to be that they were in a club and that there was a band playing in the script. It's always a kind of energetic thing to have a live performance in the film. And interestingly, that was filmed at a dance club in London; at the time, the number one dance club, the Ministry of Sound. And we shot it in a day, and got a great audience there. But it just kind of gave a different type of energy at that time, of climax. And [the characters] were slightly in an alien territory as well, because they were visiting Razor and Blade, and they had to run the gauntlet of the fans to get to where they're supposed to get to. So it was almost like The Warriors, the Walter Hill film, where these tribes are going through slightly alien territory. And so it was a different environment to the environment musically for the rest of the film. But at the same time, it gives it a great energy.

You mentioned that you've heard some of the hacking community response to this, and it sort of infiltrated the upper echelons of tech communities. I'm curious about one name in particular, if you've heard from him: William Gibson, who's literally name checked in the film as the name of the supercomputer.

SOFTLEY: That's a really interesting question. And unfortunately, no, but I certainly would love to. And I'm not sure whether he's seen the film, but I'd be fascinated with what he had to say, good and bad. But there is somebody else who introduced me and did the Q&A when I was at a particular tech and techno festival a couple of years ago: one of the most prominent, most important members of Anonymous, Jake Davis. Who has now sort of gone legit, if you like — as far as we know. And Jake said it inspired him. And there's a number of other people like that. So I think it's people of that age. And the bands who have been interviewed; the Grammys interviewed the DJs and the groups that are on the soundtrack album. And a lot of them are sort of saying that they've kind of understood, as the years have gone by, more about the film and what it was trying to do. They were slightly like, "I don't know what this film is about," when I asked them to contribute their music. But no, William Gibson, you've given me that as a kind of a top of the bucket list.

You mentioned Anonymous, and I did want to touch on that, because the kind of central ethos of the film, "Hack the Planet," reminds me of Anonymous, and their kind of central ethos. What do you, right now, think about contemporary internet culture, and how Hackers in dialogue with it?

SOFTLEY: Okay. Well I think that it's like the rest of society. It's very, very fragmented. It's very polarized. And I think that there is the potential for, as in the film, for the digital underground, the hacking, cyberpunk community, to be the whistleblowers. To tell us. And some of the people in the big tech firms have kind of resigned, left the big tech firms, and they are saying, "You guys don't know what big data is doing. What they're able to do." And in a way, the polarization politically, I think, a lot of people are saying it's as a direct result, and it seems with good cause, a direct result of the way that big tech is controlling big data. And is controlling, often through fake news, the way that the debate has become so polarized.

There's a really interesting documentary out at the moment, The Social Dilemma, and it makes it clear that the reason why fake news and the number of times people click on a fake news story makes the tech companies way, way more money than somebody clicking on the truth. Because, and they explain very, very clearly, that if you're saying that COVID is caused by 5G, that's much more sensational than saying "Well, you know, there might be a vaccine in six months. It's probable, the evidence is saying..." It's not a soundbite, in the same way, telling the truth. So I think that the, let's call it for want of a better word, the Anonymous, the hacking community, have a huge responsibility. And in many ways, [they're] probably the only people who can keep us informed and can be a sort of a barrier against the complete unanswered assault and advance of fake news. But you definitely have a huge, huge negative influence, really. Certainly in the political debate, which the accelerated take-up and proliferation of platforms and companies has created. So I think, sadly, like society, the answer is that it's very polarized.

Is there a future for Hackers? Is there any kind of sequel, reboot, reunion, any kind of return to that world in the works?

SOFTLEY: Well we are, I have to say for the first time in 25 years, and we probably started this conversation a year or two ago, in the aftermath of the 20th anniversary, I'd never even thought it was something that was interesting. Because we'd anticipate something, and then it'd happen. And then it was kind of all pervasive. Whereas, what's happened now, with big data, and the way that it's actually broke through and become maybe the dominant force in the world, in terms of influencing politics and finance and elections, that I think there is a call, for the first time ever, that the Knights of the Round Table should be woken up to sort of answer the call again. And there are a couple of conversations. It was a much more simple landscape at the time, in 1994. It's much more complex [now]. It's much more dangerous that it would become outdated almost as soon as the film's released. But there are certain cast members, certainly the guys who work with Chris Nolan, DNEG, they're approached all the time about, "Why isn't there [more Hackers]?" And on the internet, on Twitter and social media, people are asking about that possibility. So, it's being explored. But I don't think any of us would want to do it unless we thought it was worthwhile to do. We wouldn't do it as just a commercial exercise. But there has been interest, from kind of mainstream producers. So it's something that's being actively considered for the first time ever, really.

A Hackers special edition soundtrack is on vinyl now, and Hackers is currently streaming on HBO Max.