Spoilers for Halloween 2018 are discussed below.

David Gordon Green’s Halloween is a memba-berries movie. South Park coined the term when referring to Star Wars: The Force Awakens, singling out a sequel that was more about reminding people what they liked in the past rather than doing something new. What makes Green’s Halloween fascinating as a bit of nostalgia is how it tries to strip away the franchise mythology while constantly reminding you of the original Halloween. It’s a movie that can be aggressively self-aware as it tries to both dismantle the other movies and yet also place a monumental burden on the relationship between Laurie Strode and Michael Myers that the narrative does not support.

To be fair, the mythology behind the Halloween franchise was already a bit of a disaster. Starting with Halloween II, the series retconned the story so that Michael Myers and Laurie Strode were siblings and that’s why he wanted to kill her. Then it got really nutty with both Michael and Laurie dying at various points along the way not to mention a plotline that involved druids. The solution for screenwriters Green, Danny McBride, and Jeff Fradley is to basically ignore all the sequels and chalk them up to rumors within the world of their movie. This requires a character to break the fourth wall to some an extent and bring up the sibling relationship only so that another character can shoot it down.

The problem is that Green’s Halloween wants to then rest his entire movie on an epic struggle between Michael and Laurie that’s 40 years in the making. But you can’t have that if Michael is just the bogeyman. You have to make a choice: either Michael is an unthinking killing machine or he actively wants to kill Laurie Strode. It’s possible to make the argument that Laurie was scarred by Michael, and so all her actions make sense. She simply never got over the trauma she suffered in the original Halloween and that kind of ruined her entire life. But for Michael, the movie has to choose: Is Laurie important or not? There needs to be some kind of backing to this decision, even one as thin as “They’re siblings and Michael needs to kill his family.”

The original Halloween works because Michael is the bogeyman. He’s even referred to as “The Shape” in the credits, no longer human, but an entity of sorts. And that’s totally fine! He’s very scary that way even though his body count by slasher standards is relatively small (something else the new Halloween goes out of its way to remark upon). But if Michael is an unstoppable force, then part of what makes him scary is that he has no human connection. He doesn’t need to return to Haddonfield; he could go anywhere and do more killing. Laurie may have been the one that got away, but that shouldn’t matter if your thinking process is nothing more than “KILL PEOPLE.”

But Michael doesn’t go anywhere. He goes back to Haddonfield and then the film kind of waffles on whether or not he has a connection to Laurie. He doesn’t really seek her out, but he does make it a point to go back to his home town. At best, you can argue that Laurie doesn’t seem to matter that much to Michael, but Michael matters a great deal to Laurie. However, from the film’s perspective, it’s very much in line with Dr. Sartain (Haluk Bilginer), “The New Loomis”, as Laurie calls him, who believes that Laurie and Michael are connected. But that connection only matters from an external perspective, not from the perspective one of one the characters.

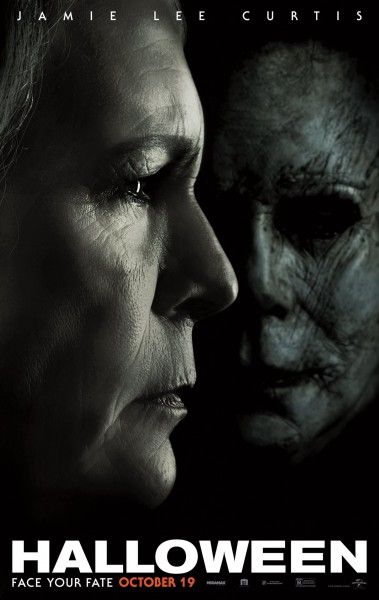

Laurie and Michael are connected through 40 years of history that also no longer exist. Green’s Halloween is forced to exist in this weird middle ground where it would prefer that the only movie you recognize is Carpenter’s Halloween, but also would like you to feel the weight of a decades-long struggle between two characters, and it can’t have it both ways. The closest it comes is Jamie Lee Curtis’ terrific performance, which sells you on Laurie’s pain and struggle over the years, but the narrative itself doesn’t justify the mythology the script seeks to erase. Halloween can either be a monumentally important horror movie with iconic characters who have reappeared multiple times over four decades, or it can be the story of a babysitter who saw her friends murdered by a masked maniac. But it can’t be both. One story is massive and epic, and the other is small and intimate, and Green’s Halloween is caught somewhere in between.

Green and his co-writers didn’t need to incorporate every single other Halloween movie into their story, but if they wanted to emphasize the weight of their conflict as one supported by time, then they needed at least work in some of the other films because Green’s picture is acutely aware it’s a movie. The film is packed with callback shots to Carpenter’s Halloween, which is nice, I guess, if you want to shriek in recognition instead of in fear. But every time Green does that or tries to hold up Laurie vs. Michael as a battle for the ages, he takes you out of the movie, because he’s no longer telling a story; he’s celebrating a franchise. The irony is that his Halloween would prefer to ignore the franchise’s existence until it needs the weight of a 40-year conflict.