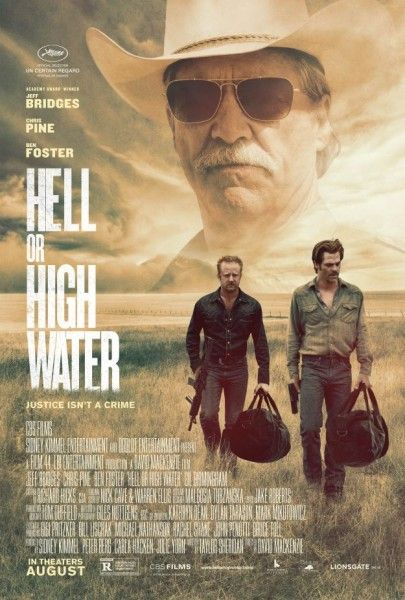

In Hell or High Water, we first meet brothers Tanner (Ben Foster) and Toby (Chris Pine) during a bank heist that they’re so early for, they have to wait for the manager to arrive with the keys. What is further revealed in writer Taylor Sheridan’s thrilling and immensely thoughtful screenplay is that we’re meeting these brothers at the end of their big plan. For the actions of robbing banks—but only the small bills from the drawers—are the last step in a masterful plan to purchase back their family land.

Hell or High Water isn’t a simple tale of bank robbers vs. the law; it’s a neo-Western dissection of the misdeeds done to the land throughout the history of the West. It features career high performances from both Foster and Pine and a delightfully nuanced old codger turn from Jeff Bridges as one of the Texas Rangers in pursuit. It’s also one of the best films of the year; an unexpected getaway car from an unusually dry summer at the movies.

Sheridan was the screenwriter of last year’s Sicario, a film that wanted to have its cake and eat it, too, by framing the majority of the film from a disillusioned DEA agent who doesn’t know what is happening and then abandoning her point of view to follow the badass and vengeful cartel assassin instead. As a script, Hell or High Water is constructed much better and is full of the stories that dot a barren landscape. High Water’s West Texas land has become unworkable for many ranchers, banks are foreclosing on houses left and right, jobs have long left (making new Western ghost towns), and the very land that was taken from the Natives of an unnamed America and Mexico is now being taken back from the settlers by the banks. With this tapestry, Sheridan’s script is steeped in history, not just of land, but how poverty is both handed down by families and preyed upon by outsiders.

By filming billboards that promise debt relief and hitting the banks whose main branch impersonally lives in the big dual city of Dallas-Fort Worth and forecloses on all the small towns where nothing is left except a family’s home, Hell or High Water might sound akin to Andrew Dominick’s recession-minded Killing Them Softly. But there is a distinct lack of American flag iconography and Presidential speeches, here. This isn’t a film about America. This is about the West reverting to the Old West.

Toby and Tanner roll through towns to rob them and the armed local citizens all attempt to be the hangin’ brigade, who’ll coral the duo until the enforcers come. But there isn’t a blanket reverence for the law enforcers, either, as they role into town as impersonally as the robbers and the bankers themselves. This distrust to all outsiders is best exemplified by a sassy diner waitress (a great cameo from Katy Mixon), who refuses to hand over her $200 tip to the Rangers because she too has a mortgage to pay. The state will have to pry it from her bank, just as the bank pries money from her.

Toby and Tanner have an intricate plan to earn a specific amount of money to buy back their family’s land that’s been foreclosed on. To give that plan away, here, would be a disservice. There’s diabolical poetry in it. But don’t confuse them for Robin Hoods. The film never makes us feel that we should be rooting for them to get off scot-free. But it is in awe of their plan.

Director David Mackenzie (Starred Up) gives equal screen time to the Rangers who pursue them, Marcus (Bridges) and Alberto (Gil Birmingham). The Rangers have an odd rapport, consisting primarily of racist prods at Alberto’s expense, which Bridges and Birmingham are able to layer as an odd show of respect and camaraderie between the forced-into-retirement Marcus and the younger family man. And Bridges, who’s played this type of mouth-agape, rumbly voiced and lonely lawman before, doesn’t let Marcus fall into caricature. There are moments of reflection, grace, and even guilt that Bridges stuffs into his ten-gallon hat. Its familiar, but it’s still one of his best performances this century.

But, as nuanced as Bridges and the script is, this film lives and dies by the performances of the brothers. And they do not disappoint. Tanner could’ve been played as an over-the-top firecracker with an itchy trigger finger, but Foster smartly winds the violent coil down until its most absolutely necessary. Instead, Foster chooses to lay on a good-for-nothin’ charm that’s all mumbled confidence and acidic humor. And instead of simply having a short fuse, Foster adds the beats of frustration that both ignite that fuse, but also drive home the idea of brotherly love.

As the other brother, Pine, who usually plays heroes, plays neither hero nor anti-hero. He is a man with a plan. He is measured. His Toby has every reason to panic. He owes thousands in child support and the bank is about to own the only thing of value he has, his land, and without a means to earn new money, the deck is stacked against him. Through an intricate plan of robberies and getaways, Pine is able to reveal that it’s the lack of panic that has kept him out of jail throughout his life and it’s the impoverished panic that’s put his brother in and out of it.

Despite their differences their is a feeling of mutual admiration between Toby and Tanner. This believable bond between Pine and Foster adds one more meaningful stitch of personal history to a script that perfectly combines the Old West with the Nu.

Grade: A-

Hell or High Water opens in select cities Friday, August 12.