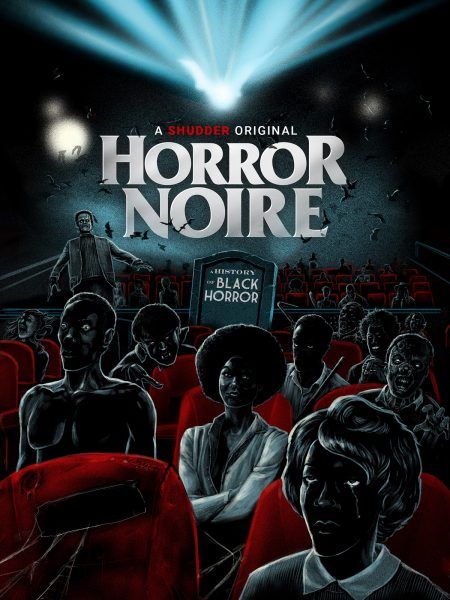

There’s a school of thought (or, non-thought, as it were) that says you should just turn your brain off and enjoy movies. If it’s not “high-brow” entertainment, then it’s not worthy of exploration. Certainly, horror films, with their low production values and cheap thrills meant for teenagers aren’t worthy of serious study. But as seen in Xavier Burgin’s excellent documentary Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror, analyzing the horror genre is perhaps most worthy of study because of how it shows us how black people are depicted in American popular cinema. Although the documentary is primarily just movie clips and interviews with black scholars, filmmakers, and actors, Burgin weaves it all together into an engrossing story of American cinema. Horror Noire never professes to be a complete history of black cinema, but it does show how certain tropes appear in horror films with regards to black characters. By analyzing these tropes, Burgin, along with writers Ashlee Blackwell and Danielle Burrows, emphasizes not only a lesson in black representation, but the importance of analysis in making sure that representation is accurate and equitable.

Horror Noire wisely starts with a look at Get Out, a black horror film that will be known to both white and black audiences, and a film that’s an undeniable success having earned $255 million worldwide and an Oscar for Jordan Peele for Best Original Screenplay. The movie then goes all the way back to D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation to show the evolution of black characters in cinema. Burgin carefully walks his audience through black representation, showing the damning effects of Birth of a Nation portraying black men as monsters out to get white women, to the elimination of black faces by making them faceless monsters for white people in the sci-fi horror of the 40s and 50s, then the massive impact of Ben (Duane Jones) in Night of the Living Dead, the double-edged sword of Blaxploitation and beyond. Burgin carefully notes when the intersection of film and history happen, like how the civil rights movement intersects with Night of the Living Dead, and how they feed off each other. He also shows how the Reagan 80s marginalizes black characters to supporting roles where they’re either not present in the suburbs or simply there to die. But as tropes become more tired and unacceptable, cinema starts to change and evolve.

What’s wonderful about having Horror Noire talk to scholars, filmmakers, and actors is that it allows for nuance in the criticism. If the film had only been scholars, it would have missed out on the behind-the-scenes stories of how movies like Blacula got made. If it had only been actors, it may have missed the critiques that scholars can make by looking at the whole history of cinema. And what’s more, when these two sides disagree, Burgin invites that disagreement, which makes Horror Noire feel more honest. The scholars can point out that in the 80s, black actors were taking these marginalized roles where their character was waiting to die, but the black actors can counter that it was valuable to get their characters on screen so that black audiences could see themselves in movies. It’s not that one side is “right” as much as both arguments have their merits.

Even though Horror Noire covers a lot of ground in its 83-minute runtime, the movie never comes off like a crash course. Instead, it feels like Burgin is doing a bunch of miniature critiques and then inviting the audience to see the film and analyze it for themselves. Even though less than ten minutes is spent discussing Candyman, you feel like you’ve got a full appraisal of the film’s strengths and weaknesses. You can see its value in giving a black man the power of a supernatural entity while still recognizing that it plays into the trope of the “evil” black man going after a “pure” white woman.

The chronological structure of the movie keeps everything intact so even if different movies have different themes that are being explored, Burgin and his subjects always keep the focus on how representation is developing and how it relates to the time period. When the interviewees are talking about Tales from the Hood and a scene of police brutality, it ties into the Rodney King beating from 1991. When black people are allowed to tell their stories, it gives you something very different than what white directors are offering—horror films where black characters simply exist to either die or show how strong the monster is and then die. While I doubt Tales from the Hood will end up on Sight and Sound’s Top 100 Films of All Time list any time soon, Horror Noire shows the value of watching and talking about the 1995 horror film and its ilk.

And for Burgin, these discussions are what move the culture and cinema forward. Once you’ve identified “The Sacrificial Negro” or “The Magical Negro”, people will usually want to avoid the cliché although it still pops up from time to time (as it does in Annabelle with the Sacrificial Negro trope). It’s not simply a matter of pointing to something and saying, “That’s problematic!” but explaining that such characters are dehumanizing and tend to exist for the benefit of white characters rather than having agency and desires of their own. But once we recognize the problem, we can do better. Denial gets us nothing, and the education Horror Noire provides is essential to gaining a stronger understanding of both cinema and American history.

Anyone who claims to be a film fan owes it to themselves to watch Horror Noire. It’s the kind of movie that will have you reevaluating the genre and the history of cinema through black characters who have typically been marginalized or even erased completely. Burgin’s assessment is thoughtful, even-handed, and will spur you to add a bunch of horror films to your watch list. Rather than turning off your brain when looking at horror, Horror Noire shows there’s so much more fun and enlightenment to be had when you engage with the material, whether it’s an acclaimed Oscar-winner like Get Out or a blaxploitation flick like Blacula.

Rating: A

Horror Noire is now available on Shudder.