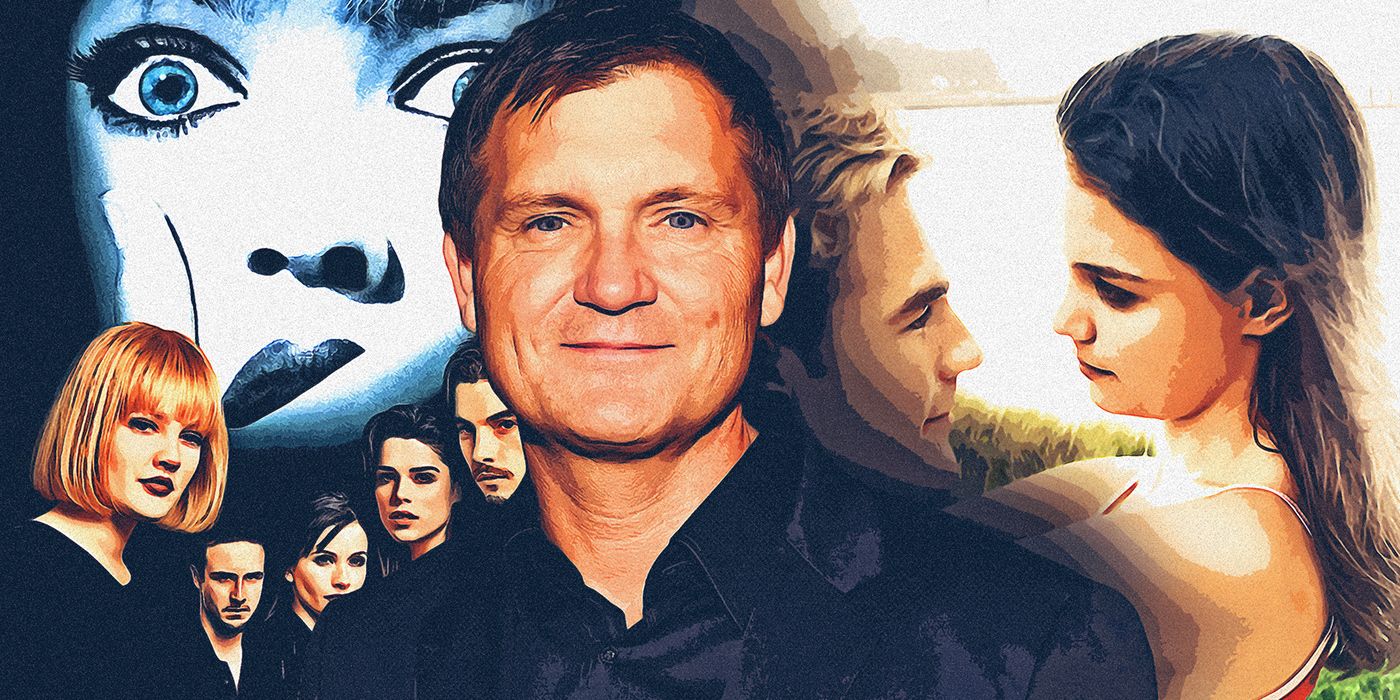

Kevin Williamson is both prolific and unsung. Either passed over for — or uninterested in — the DC and Marvel money collected by his peers, the man is a dialogue ace and an efficient, effective establisher of character, but is rarely cited as such. Even when the final products themselves are being celebrated — as is often the case with his early work in particular — much of the credit goes to his directors or his actors, with his writing often mentioned in passing. Maybe it’s his early-aughts stretch of TV work that didn’t quite click. But attachment to middle-of-the-road network and streaming dramas shouldn’t be memory hole-inducing dark marks on a resume filled with imitator-employing high-water marks.

There’s a scene in the 2022 slasher milestone Scream where one of our protagonists is laid up in the hospital fretting about their safety, as one does when a ghost-faced serial killer is on the loose. This character bides their time awaiting news of their sequel prospects by watching a show that soothed an average of 7 million viewers per episode in its glory days, which started in January 1998. That show is called Dawson’s Creek.

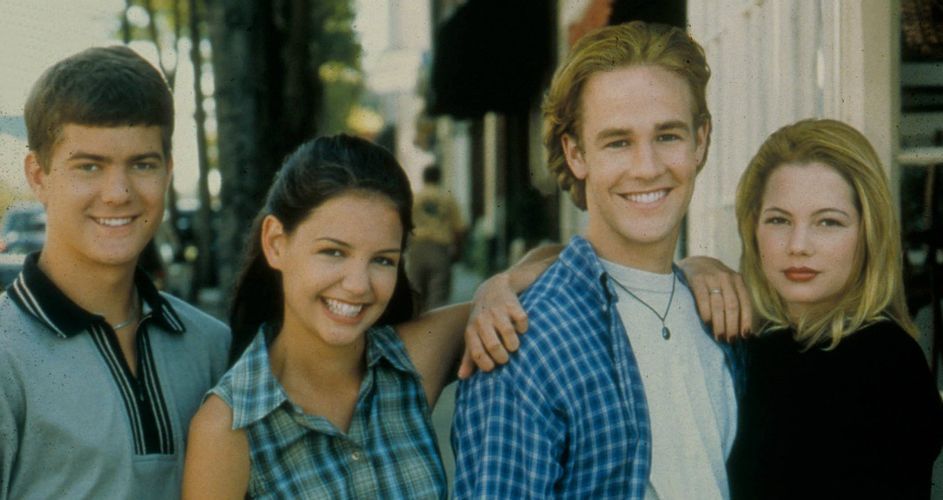

Created by Williamson after the original Scream (which he also wrote) won him everyone’s attention, Dawson’s Creek was pitched to executives at the WB as a semi-autobiographical show with elements of My So-Called Life and Little House on the Prairie, and the proof of that influence is in the final product. Starring the destined-for-fame quartet of Michelle Williams, Katie Holmes, Joshua Jackson, and James Van Der Beek, the show took its network — then the underdog home of 7th Heaven, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and some struggling-but-serviceable sitcoms — and fused it with the 17-25 demographic, which it would hold onto for the remainder of its existence.

To speak with colloquial frankness, Dawson’s Creek rips. For a show born in 1998, the things that come out of its characters’ mouths are blush-worthy, and the plot developments soap-worthy. On the outside, it looks dowdy and wholesome, and that’s a vibe reinforced by its iconic, minivan-core theme song. But it’s a show that pulses with a sexual charge that no scene ever really ignores, as well as a show with the art of film on its mind, with the titular Dawson dreaming as much about being the next Spielberg as kissing the new girl in town. The dialogue is razor sharp and hyper-literate, with as much hand wringing over the show’s adult directness as about its highly verbose scripts.

Is this really how kids talk? That was the question. It’s a question that missed the beauty in the point: that however kids talked, the show refused to talk down to them. This was Williamson’s third time illustrating this aspect of his style. The first was just two years prior to the show’s debut.

In 1996, Scream was released and went on to make $173 million on a $15 million budget. It rewrote the rules of horror movies, perhaps irrevocably. No more could your characters be intolerably ignorant of what kind of movie they were in. They didn’t have to name-check John Carpenter films, but they could no longer run upstairs to evade a murderer without garnering groans from a newly educated audience. How significant a paradigm shift this was, it was easy to overlook the other rule being rewritten. That of how to handle teenage characters.

Further solidified by Dawson’s and the head-spinning quantity of screenplays and rewrites delivered by Williamson in his initial creative surge (between October 1997 and December 1998 there was I Know What You Did Last Summer, Scream 2, Halloween: H20, Dawson’s Creek season one, and The Faculty), the scribe walked teen drama from the niche satire in vogue at the time toward an alternate future where the next John Hughes reads Lois Duncan novels instead of National Lampoon magazine.

The influence of My So-Called Life on every teen drama that arrived in its wake cannot be overstated. Years before mumble core entered the movie nerd lexicon, that show acted as a 19-episode how-to on treating the problems of teenage characters with the same care and importance as the problems of adult characters, and not with a tidy lesson at the end. That show’s young cast liked and whatever’ed its way through dialogue that laid bare their angst, fears and crises of identity. It made life look hard and relatable, but it did not find an audience when it needed it. Someone who clearly was watching, though, was Williamson, who borrowed one of that series’ most meaningful elements — depicting teens as expressive and emotionally intelligent, and depicting their parents as being more experienced but not necessarily knowing better.

In Williamson’s hands, the likes and whatevers were replaced with GRE prep words and the brooding pauses with zippy and sardonic one-liners. Pop remixes of alt-rock bangers. He was soon boxed out of the motion picture variation of his career, for the most part. Like many an influential hit, the ingredients were easy to imitate if not the quality. Scream birthed years’ worth of B-level teen horror films, but Williamson himself almost never handed in another script that wasn’t taken from him and reconfigured by studio notes and/or other writers, contorted into different beasts entirely. Even Scream’s reboot leans into the pulse-quickening frame-control of Wes Craven and away from the audience-bonding character-control of the original’s writer.

That writer’s influence is more felt in the realm of television. There would be no Gossip Girl, the OC, Ginny & Georgia, Riverdale, Pretty Little Liars, One Tree Hill or Gilmore Girls without the trail blazed by Dawson’s Creek, at least not in the shapes they ended up taking. Many of them were greenlit specifically because of Creek’s success and the number of young TV fans — especially young women — that it proved were out there and not being spoken to.

In 2009, Williamson and producing partner Julie Plec (former assistant to Wes Craven) struck genre gold in a way that had proved elusive for them after Williamson’s initial success — they created the Vampire Diaries, the renewable energy source of a television universe based on the series of young adult vampire novels of the same name. Running eight seasons and spinning off shows that run to this day, its development was prompted in part by the success of HBO’s True Blood, the very adult hit that debuted one year prior, based on a different set of vampire novels. If there could be a “surprise hit” vampire property released during the post-Twilight vampire property gold rush, the Vampire Diaries would be that surprise. Particularly in its second season, the show helped to solidify the narrative language of the WB-to-CW series that would follow, including the Greg Berlanti DC projects that would come to define the network: namely, season-long serialization with fewer Supernatural-style cases of the week, and breathless twists and cliffhangers (it should come as no shock that Berlanti’s first production credit is for — you guessed it — Dawson’s Creek).

There are worse things to be than a consistently working writer with a handful of hits under their belt, and few more enviable positions for any writer than to have celebrated work, even if your name isn’t the thing being celebrated alongside it. But as the world sifts through its box of artistic legacies in search of art and artist marriages worth talking about (and worth mimicking), and especially as elevated horror is in demand alongside elevated teen drama, there is copious benefit in understanding who the greats are and breaking down what makes their stuff work. As such, it is time Kevin Williamson got added to the list. The highest of his highs have by now earned more than just a passing reference.

-7.jpg)