Growing up with Disney films of fairy tales, it’s easy for young viewers to get caught up in the romantic fallacy of beauty and love. The image of a handsome young prince and equally stunning princess riding off into the sunset becomes the customary visual representation of love. Youth equates to beauty, which then gets used as currency for attaining love. However, much of these expectations of grace and ethereal beauty rely so much on their female protagonists.

In Cinderella, appearance is so important that she needs to completely change her look and wear a beautiful ball gown and glass slippers just to get through the castle doors. In Snow White, it’s the stepmother’s obsession with being the “fairest of them all'' that prompts her to kill her stepdaughter because there can only be one. In Shrek, it’s about aligning Shrek and Fiona as equals through their shared aesthetic as ogres instead of living with the way they are, Fiona as a human and Shrek as an ogre.

The common thread here is the obligation to change one’s appearance for love to be attained. At the very least, beauty is addressed in the context of female agency to gain that agency. In contrast, male agency seldom depended on their own need for physical validation from their female counterparts or the world they inhabited.

Beauty and vanity are usually assigned to the female character. What happens when vanity is aligned with masculinity? Male characters in these fairy tales are often indifferent to their beauty. What happens when male characters are just as dependent on their looks as female characters are made out to be? Or when they hurt others to uphold this impossible beauty standard? It opens the door to discussions about who creates these arbitrary standards enforced on female characters and who is imposing them.

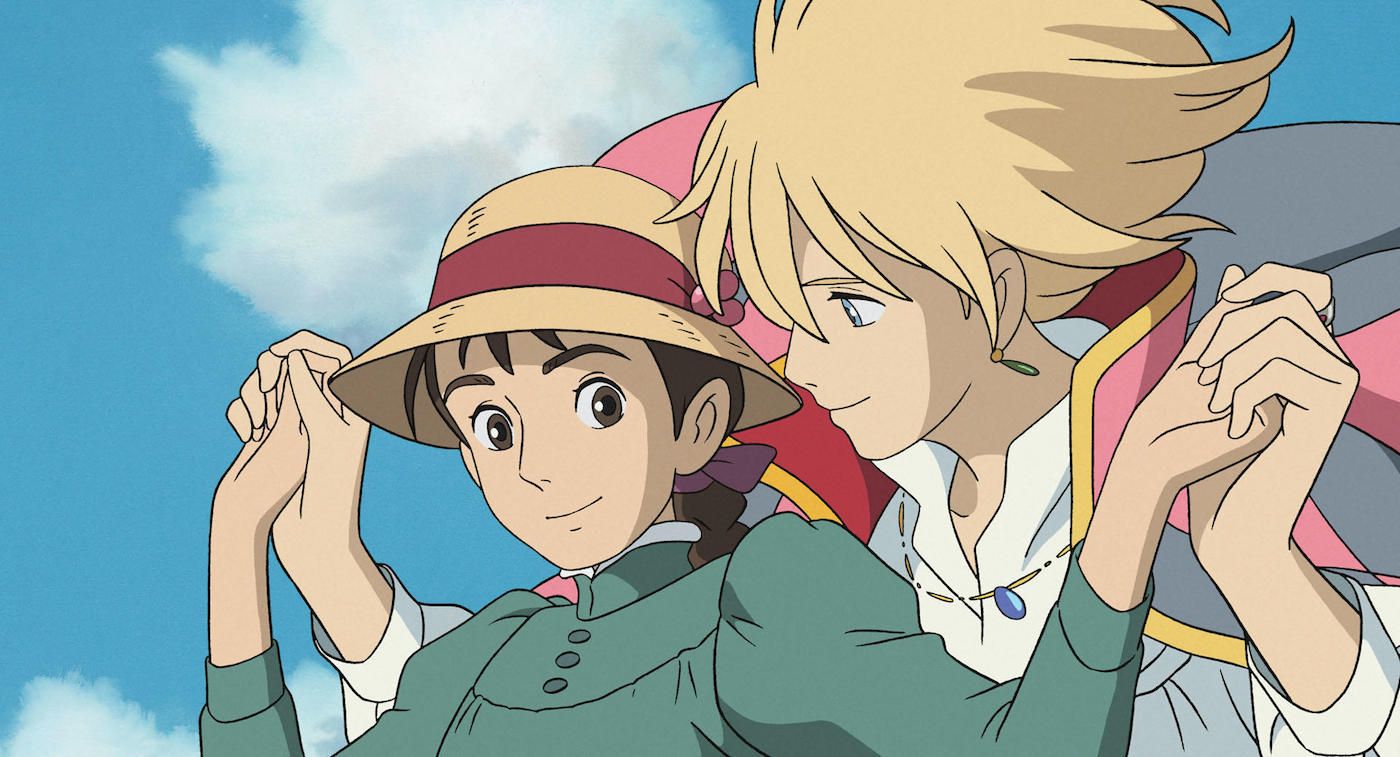

In Hayao Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle, love becomes this point of tension with age and appearances. It is also a gendered experience that becomes reversed. Howl, voiced by Christian Bale, a powerful young wizard, also struggles with his narcissism and becomes the focal point of expectations of beauty. Some of these concerns would manifest in physical ways that altered the entire mood of the castle that they reside in and his soul.

By connecting his expectations of himself to his soul, the film sets up this dichotomy of exterior and interior. By the end, when Howl cuts that tie between the physical and the metaphysical by rejecting an idealized version of himself, he’s also breaking away from the social constructs of beauty in general. Throughout the film, Howl’s journey is about managing expectations of physical and emotional beauty. He slowly detaches the idea that his worth is strongly linked to how his magic makes him look instead of what he can do with it.

Howl’s characterization is so refreshing to films centered around young love because it’s his vanity that becomes wrapped up in the caveats of love, not Sophie’s. He’s the one concerned about his youth, beauty, and maintaining both for as long as he can. There’s an exciting gender reversal where the audiences begin to understand the impossible standards set by Disney films with their female characters. Only this time, they see it through Howl. It is a blatant gender reversal, where Howl is by no means unattractive within these measures but does feel pressured to stay within the confines of these standards.

Much like Cinderella, Howl doesn’t start or end any differently regarding his physical appearance. However, his transformation didn’t require some physical montage on how the “exterior should match the interior” like Cinderella did. A glass slipper was unnecessary to prove Howl’s identity. All the changes happened within Howl’s perception of others and himself. He did not require Sophie or anyone else to match him where he stood but instead began to be that person to others.

As opposed to altogether rejecting beauty standards as Shrek did, Howl’s Moving Castle emphasized how these standards get applied to their male characters and accept them for what they are. However, by the end of the film, it wasn’t a matter of either Sophie, voiced by Emily Mortimer, or Howl picking a physical appearance that adhered to both of them but accepting one another for their differences. In Shrek, you have Fiona turning into an ogre-like Shrek to establish a balance of power.

What is more powerful when it comes to love and beauty standards? Having to change to conform to the other person or accept one another for the way they are? Howl’s Moving Castle draws these comparisons in a way that, by the end, doesn’t matter. Howl isn’t concerned much about the way he looks any more than Sophie is. Except, it was Howl who endured the weight of beauty expectations a female character like Sophie would typically have had to.