Among the many atrocities committed against popular culture by The Big Bang Theory, there exists only one that equals the sheer, breathtaking obnoxiousness of coming across a Young Sheldon poster without warning. I speak, of course, of the way the show brought to light and legitimized a piece of geek criticism once reserved for the darkest, most annoying corner of your local video store: The "Indiana Jones Doesn't Matter In His Own Movie" theory. Folks, I hate it, and on Raiders of the Lost Ark's 40th anniversary, it's finally time to put the dang thing in the dirt. Not necessarily because it's "wrong" or "right", but because it fundamentally doesn't work as criticism and ignores what makes cinematic storytelling powerful in the first place. It does not, to be clear, belong in a museum, unless "a museum" is what you call the dumpster out back.

As explained in the 2013 episode "The Raiders of Minimization," the idea posits that Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford) has no effect on the outcome of Steven Spielberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark; had Indy simply stayed at home, the Nazis still would have opened up the Ark of the Covenant and melted like a package of aggressively racist Peeps put in a microwave. TBBT didn't invent the idea—it's probably been circulating since the first uber-nerd left a matinee in 1981—but it did turn it into A Thing, sparking headlines like "How The Big Bang Theory Ruined Indiana Jones For Everyone" and "Has The Big Bang Theory Ruined Indiana Jones Forever?" and ensuring you'd have to hear about it every time you see that cousin whose 10,000-case Blu-ray collection is just different releases of the same three Michael Mann films. It's become one of the most common "did you ever notice this?" topics in cinema history, rivaling Daniel LaRusso's illegal crane kick and that Stormtrooper who bonks his head on a doorframe.

The Theory Misses the Point of Indy

But Indiana Jones has no effect on the outcome of Raiders of the Lost Ark because that's not the story of Raiders of the Lost Ark. That would be Indy's emotional arc, crystal clear from the moment we meet him. That opening trek through the trap-filled temple is masterful stage-setting, but its undercurrent is what it eventually tells us about Indiana Jones. "I had it in my hand," he tells Marcus Brody (Denholm Elliott), ignoring the several dozen times he almost died while also tying the historic significance of the find to his own personal glory. Ford's charms always smooth the character's edges, but my guy opens this film as the dictionary definition of cocksure. No man in history has ever been more sure of the cock. Ford pulls off a wonderful transition between Indy explaining the Ark's mythology to two Army Intelligence agents—scholarly and buttoned-up, selling the awe of the artifact—and the very next scene. My guy is in a damn bathrobe, itching for Brody to say he's got another chance to make archaeological history. He straight-up laughs off the "taking on a well-funded battalion of Nazis" aspect of the mission because he packed the good revolver. More importantly, he scoffs at the purported power of the Ark. "You know I don't believe in magic, a lot of superstitious hocus-pocus," he tells Brody. "I'm going after a find of incredible historical significance, you're talking about the boogie man."

The entire rest of the film is nature, mankind, and God himself saying "Indy don't do this" and Indy doing it anyway. "If it is there at Tanis, then it is something that man was not meant to disturb. Death has always surrounded it," Sallah (John Rhys-Davies) tells Jones, seconds before a Nazi monkey eats a poisoned date, universally recognized as A Bad Sign. Uncharacteristic lightning crackles over Cairo as Indy gets punched, shot at, walloped, and otherwise tossed around, but the shining thought of the Ark at the end of the road keeps him persevering well beyond what a body should handle. It's incredibly endearing—it's why we love Indiana Jones!—but it's also one step to the left of madness. Belloq (Paul Freeman) tells him as much, in a classic we-are-not-so-different-you-and-I speech. Indiana Jones is handsome, charming, and comes with the tremendous benefit of being played by Harrison Ford, but he's still a human wrecking ball who comes to other counties and cultures and causes an absolute ruckus under the guise of archeology. Boiled down, he's one desperate decision away from becoming a villain.

Why This Climactic 'Raiders' Scene Really Matters

“Archeology is our religion, yet we have fallen from the pure faith," Belloq says. "Our methods have not differed as much as you pretend. I am but a shadowy reflection of you. It would take only a nudge to make you like me. To push you out of the light."

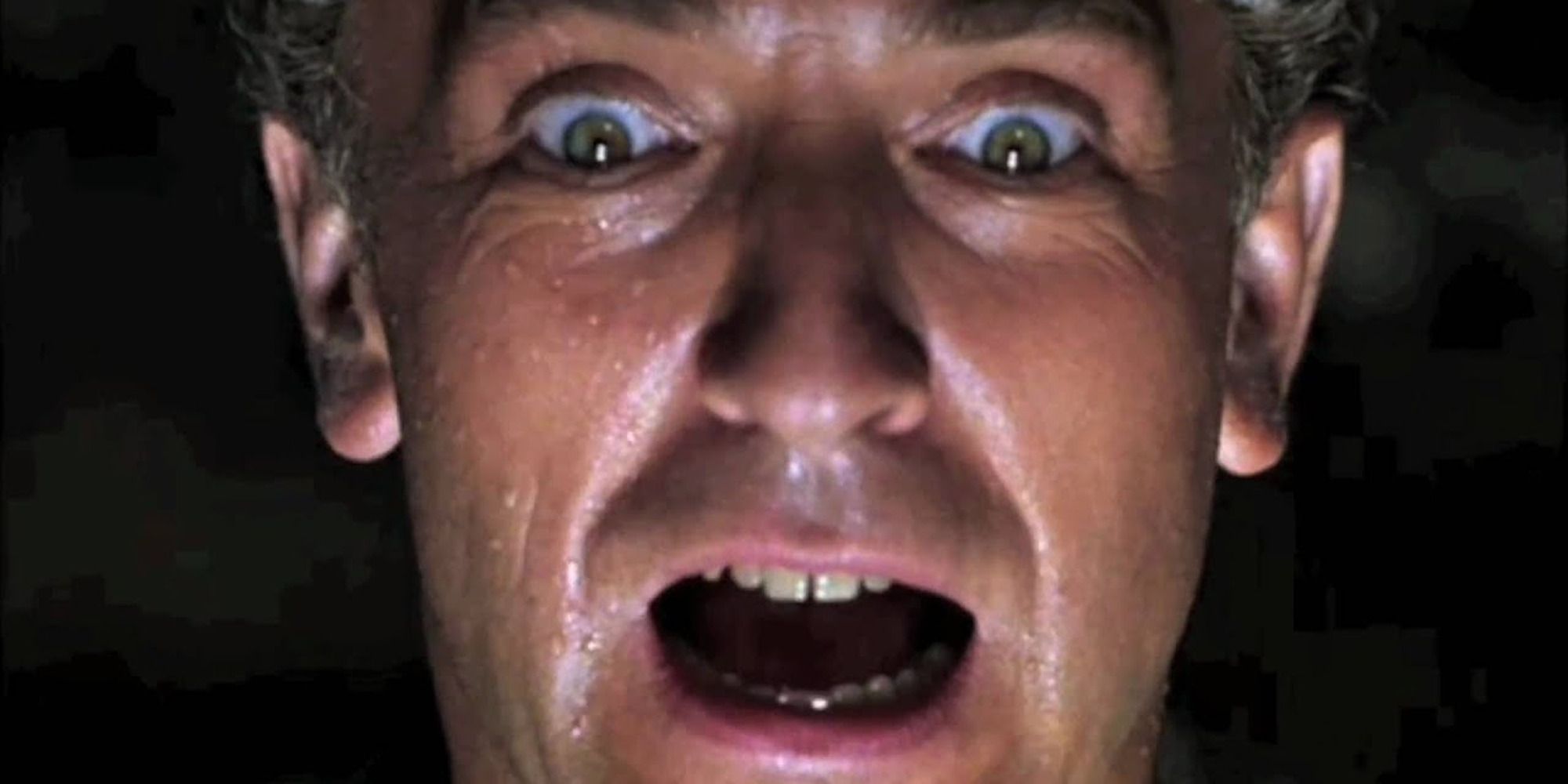

That is what makes the climactic Ark-opening scene so powerful. There's no real indication of why Indy tells Marion (Karen Allen) to close her eyes because it's an act of pure faith; it's a man who didn't believe in "superstitious hocus-pocus" recognizing he's in the presence of something tremendously beyond himself. More than that, it's something he can't just bullrush his way through. In that moment, Spielberg and George Lucas' vision of a modernized 1920s adventure serial is solidified, because it's the type of vulnerable character development never afforded to the he-man heroes of old, the ones who simply kicked ass and rescued damsels. Instead, Indiana Jones closes his eyes, and Belloq, the man who stubbornly stuck to his ways, gets his face blown off like a faulty Roman candle.

To be clear, this all also 100% does have an effect on the film's ending, it's just way more cynical an ending than nostalgia might allow you to remember. (As Spielberg's career progressed it became more and more obvious this was no accident.) Sure, without Indy, the Nazis might have brought the Ark back home and blown the Third Reich to pieces, and that's pretty fun to think about. But Indy (and, by extension, America) did intervene, and now the most powerful artifact on the face of the Earth—one that didn't belong to the U.S. in the first place—sits useless in a warehouse, America deciding to squash a culture instead of study it. It's the sketchy, invasive undercurrent of the Indiana Jones character writ large, but as Indy walks away with Marion as the credits roll, he's a part of it no longer.*

The Theory Represents a Bigger Problem

This is all to say, "Indiana Jones Doesn't Matter" isn't annoying because it's "wrong"—Indiana Jones is not directly responsible for a Nazi regiment being struck down by the wrath of God, this is true—but because it's emblematic of the type of I-must-be-smarter-than-the-movie criticism that's ruining the way we talk about movies. It's almost designed to miss the point. It's the film-as-riddle mindset that first formed alongside the birth of the internet but really crystallized into something insidious somewhere between the mid-point of Lost and the exact moment Inception cut to black. "Indiana Jones Doesn't Matter" is the personification of the idea that films and television shows are something to be solved instead of felt; that stories are static objects made of ones-and-zeroes and to remove the flawed piece of data sends the whole thing crumbling. (Thus making you The Internet's Smartest Boi that day.) But movies are, in Roger Ebert's words, "machines that generate empathy"; whether it's a quiet character study or a globe-trotting adventure, the joy comes from living another life for a few hours. That is the result of character, not plot, and Indiana Jones is the type of character whose arc is supposed to have holes.

(*"Oho!," you might be exclaiming, "but what about Temple of Doom, the prequel that establishes Indy has experienced magic, or The Last Crusade, the sequel that sees Indy galavanting against the Nazis once again!" The simple answer is that Steven Spielberg and Co. didn't know there'd be more movies when they made Raiders in 1981. That is how filmmaking and also the passage of time works. The even simpler answer is please go back and read the paragraph immediately preceding this one.)