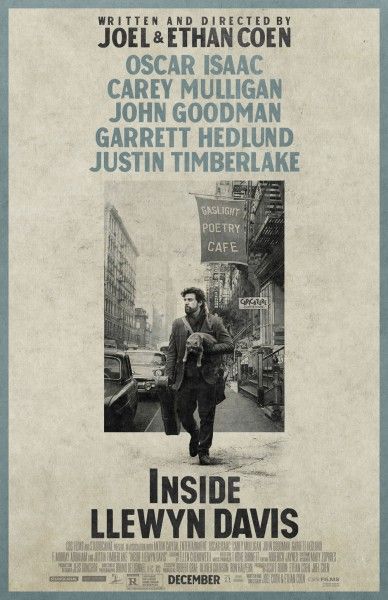

[This is a re-post of my review from the 2013 New York Film Festival. Inside Llewyn Davis opens today in limited release.]

It’s a terrible thing to feel like you’re not the protagonist of your own story—to simply exist with nowhere to go. Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac) is a man who doesn’t fit into his own life, and in the Coen Brothers’ most melancholy film to date, Inside Llewyn Davis, we’re taken on the moving journey of a folk singer trying to succeed in the right place at the wrong time. He can’t create a future from the songs of the past, and he lives ambivalently in the present. Toning down the stylized hyperrealism of their previous movies, Joel and Ethan Coen have created a work that still bears their signature, yet takes them and us to a restrained, yet tonally and emotionally frustrating place. Anchored by a subtle, touching performance from Isaac, as well as beautiful renditions of folk songs, Inside Llewyn Davis is a somber look at a wandering musician.

Set among the Greenwich Village folk scene in 1961, Llewyn Davis trudges through a meager existence trying to make it as a solo folk artist. The story follows a week in his life, opening with his sorrowful rendition of “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me.” He then goes out to the venue’s back alley, where he’s attacked by a shadowy figure. Llewyn’s fortunes don’t improve. He’s stuck carrying around his friends’ cat after he accidentally lets it out and the door locks behind him. He then visits Jean (Carey Mulligan), who hates his guts and is possibly pregnant with his child. Llewyn has seen no royalties from his record “Inside Llewyn Davis,” he’s almost entirely lost his love of music, and he doesn’t even have a winter coat to protect him from the bitter cold. All he has is other people’s couches as a place to crash, and the last shreds of hope that his career might take off.

As with all of the Coens’ movies, the film is incredibly conscious of its setting, and this setting in particular not only informs the tone, but also creates a fascinating departure from their previous movies. Cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel presents a muted palette cloaked in grey and uses a documentary-like approach, but with almost no hand-held camerawork. It’s a colorless and lonely world with no reprieve for Llewyn. He’s homeless and will sleep on the couch of an almost total stranger if it means a place to stay for the night. The best he can do is to keep moving, drag around his guitar, and muddle through the hardships constantly befalling him.

Despite draining the movie of its colors and rooting it in a firmer reality (real-life singer-songwriter Dave Von Ronk provided the inspiration for the lead character), the Coens maintain their ability to create compelling characters, left-of-center interactions, and unconventional storytelling. Their pitter-patter dialogue is still present, although appearing with lesser frequency than their previous movies. Slightly oddball characters pop into Llewyn’s world, such as an easygoing army private/folk singer (Stark Sands) and a sneering, dismissive jazz musician (John Goodman), whose valet is a taciturn greaser (Garrett Hedlund).

At best, Llewyn reluctantly accepts people into his life, but usually he’s either rejecting the few people who show him an ounce of kindness or being rejected by everyone else. He’s not an unrelenting bastard, because that would take strength he no longer has. The most he can muster is a snide remark or casual insult, unless someone pushes him to confront his emptiness if not his ennui. Everything good or hopeful that comes from Llewyn is in his music, even though his passion for it dwindles further every passing day. He’s caught between a profession he’s tired of pursuing and a love of music his performances can’t hide, even though the songs aren’t his. It’s an expression of someone else’s words, so he can only be the singer rather than carry songwriter hyphenate.

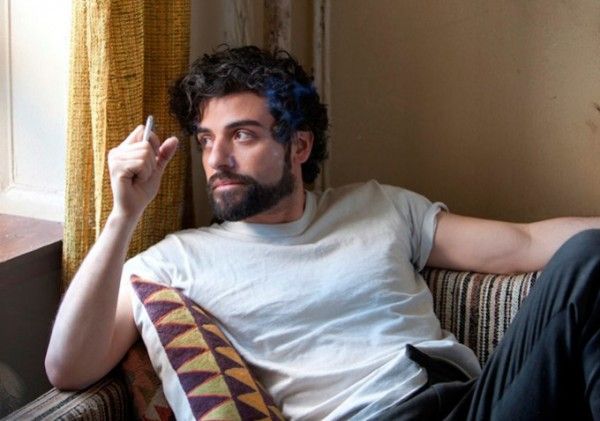

Like the Coens, Isaac pushes the tragic, weary nature of Llewyn without making the character and the movie feel utterly bleak and hopeless. Isaac’s performance is mostly in his jaded, weary eyes. They aren’t the eyes of a man who has seen it all, but the eyes of a man who feels ambivalent about almost everything he sees. Ultimately, though, he can’t hide his love for the music, and while his demeanor suggests that he’s on the verge of giving up the folk scene, his passion comes bursting through when he sings. Isaac’s renditions of the classic folk songs are powerful from start to finish, and they help to provide color the movie so desperately lacks.

Not since O Brother, Where Art Thou? has music been so essential to a Coen Brothers’ movie. Inside Llewyn Davis takes the importance of music one step further by having every song performed in full rather than piecemeal, like most of the music in O Brother. Musically, Llewyn Davis is a spiritual sequel to O Brother, since the folk music featured here historically originated from the music featured in their 2000 film. Although Llewyn sings some of the same songs as Von Ronk, Isaac lends his own voice to them, and all of the other tracks have a unique feel that emphasizes the importance of the singers, even if they’re not the songwriters. In fact, the only original song is intentionally horrid “Please Mr. Kennedy,” a cloyingly peppy, faux-folk tune that is anathema to the more authentic folk Llewyn sings, but he has to play backup on the track because he needs the money.

There’s no romanticism in Inside Llewyn Davis, nor is there an oppressive realism. The film is even content to drift away into a sense of meandering whimsy when Llewyn goes traveling with the jazzman and the greaser, although their road trip almost pushes the audience to the point of indifference rather than ambivalence. The movie draws us in because we can’t easily define the character. He’s not a sad sack or ragingly self-destructive. He can’t catch a break even when someone throws it to him. There’s simply no place for him, and he has to face that loneliness every moment. Inside Llewyn Davis can be heartbreaking. I started tearing up at the end, but it wasn’t out of pity or depression. It was out of watching someone who has faded after losing almost every refuge, yet who still struggles to do more than exist, even if his existence has become exhausting.

Rating: A-