Spoilers ahead for Interstellar.

Christopher Nolan has an awkward relationship with emotion. It’s not so much that his movies are cold and distant as much as their emotional beats feel programmed in. They’re as carefully constructed as any other element, and they can be quantified as such. You need X number of scenes wrestling with the memory of a dead wife or these number of beats to make sure the joke lands. Nolan’s work, frequently concerned with both time and truth, deals with the precision of both. That perceivable precision is partly what has earned him such a devoted following as you feel like you’re looking at a beautiful timepiece when you see the construction of Nolan at his best (The Dark Knight, Inception) and wondering how he went astray at his worst (The Dark Knight Rises).

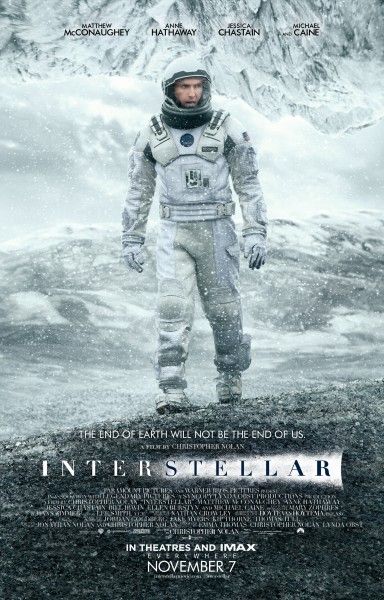

Interstellar is the kind of movie that only Christopher Nolan could make, not only because of its concerns with love and its occasionally sterile approach to human emotions, but also because no other filmmaker gets to make such a big, audacious works that channel heady sci-fi like 2001: A Space Odyssey. Other filmmakers may get to track this ambition with something more workmanlike such as The Martian or with a lower price tag like Ad Astra, but Nolan made an unapologetically scientific movie about human exploration, time dilation, and a climax about representing the fifth dimension in a three dimensional space all to come back to a story about a father reconnecting with his daughter to save the human race.

Interstellar is Nolan’s most unabashedly emotional work to date, and yet even here, the film wrestles with how to convey that emotion. The central conflict is magnificent as Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) is frequently faced with the choice of wanting to return to his family and needing to save the entire human race. As a parent, you want your kids to survive and flourish. You can see this at the very beginning of the movie when Cooper is frustrated that his son Tom (Timothee Chalamet, Casey Affleck) won’t be going to college simply because he didn’t score high enough on a single exam. But he tries to take comfort in the knowledge that Tom will be a good farmer. There will be a future for Tom. The stakes come when Cooper learns that unless humanity leaves Earth, there won’t be a future for anyone.

That makes Interstellar largely about the importance of letting go. The need to leave Earth behind mirrors Cooper’s knowledge that he’ll have to leave his kids behind. Even if they hate him for it, or choose to forget him entirely, it doesn’t matter because of a parent’s responsibility to their child is to ensure their survival. That may be a cold, biological way to look at childrearing, but it provides the thematic crux for all the scientific stuff that decorates Interstellar. The movie isn’t about time dilation or even really about the importance of space exploration. The whole movie is about trying to quantify as scientifically as anything else our love for each other. Love, far from a simply social utility, is a force as powerful as time or gravity.

The strength and weakness of Interstellar is trying to make that case, and the film stumbles when Nolan isn’t willing to trust his audience to understand that central theme. That lack of trust can be surprising in a film that’s so audacious in everything else it does. The craftsmanship of Interstellar is off the charts. It has one of Hans Zimmer’s best scores. The production design is inventive and unique (I love the design of TARS). The film brings one of Nolan’s foremost concerns—time—into a practical resource that constantly works against the characters (time as the enemy also factors largely into Dunkirk). It is a true science fiction epic that takes big swings, takes time to explain why a black hole is three dimensional, how wormholes function, and more.

On a macro level, Interstellar is nothing if not impressive. When you see the frozen clouds and craggy surface of Dr. Mann’s (Matt Damon) planet, you can’t help but taken in by the magnificence of the terrain. Even the knee-deep water planet has its own majesty as Nolan takes us to worlds we never really imagined before. Through all of this, the movie knows how to keep the immediate stakes going while also maintaining the larger save-the-human-race conflict. When they land on the water planet, the amount of time running out affects not only Cooper losing time with his children, but also the time left to save humanity from the devastation of the Blight. Throughout the film, the fate of humanity is interwoven with the fate of Cooper’s relationship with Murph (Mackenzie Foy, Jessica Chastain, Ellen Burstyn).

Where Interstellar stumbles is in how it tries to depict that relationship. It’s not that the humanity doesn’t come through. On the contrary, the most emotional scene in the movie is when Cooper gets the years of messages from his children, sees how they’ve grown up without him, and how they’ve turned their back on him in his absence. But Nolan’s penchant for explaining science spills over into explaining the movie’s central theme. It’s a record-scratch moment when Brand (Anne Hathaway) tries to explain how love works. Yes, it has a payoff when Cooper is cycling through the 5th dimension and exclaims, “Love, TARS, love. It's just like Brand said. My connection with Murph, it is quantifiable. It's the key!” Trying to bridge the gap to take love from a romantic to a scientific notion renders the emotion inert. If love can be quantified, it loses its power since it can then be compared and contrasted. That doesn’t mean it’s not a valuable force, but it’s like trying to attach an emotion to gravity. In explaining how love works, Nolan inadvertently deprives it of its impact.

This kind of misstep crops up again at the end of the movie when Cooper arrives on the space station. Much has been made that when he finally sees Murph again, they only share a brief interaction before he leaves to go find Brand. That doesn’t bother me so much anymore because as I’ve said, Interstellar is about letting go. Cooper walking into a room full of his descendants is about the legacy he’s left behind. He did what he was supposed to do as a parent in ensuring his child’s survival and letting her know he always loved her. What’s upsetting is that Cooper is largely unconcerned with what happened to Tom. Even if Tom is dead by this point, it’s pretty cold-hearted to not even show any curiosity about the fate of his son, and it undermines the film’s point about what parents owe to their children.

These may seem like minor missteps, but like the relativity that affects our astronauts, little moments have major ramifications on Interstellar’s careful construction. Because the film doesn’t perfectly land its emotional beats, we end up overlooking the movie’s strengths. When you’re sitting with the movie, it really does manage to suck you in and make you care about scientific concepts, but it rarely inspires. It manages to make you care about the father-daughter relationship between Cooper and Murph, but only sporadically. Even Nolan’s obsession with truth and lies feels a bit flattened as the film’s liars, Professor Brand (Michael Caine) and Dr. Mann, are rendered into pathetic creatures who lost hope and focused only on their own survival.

When you look at the tight construction of The Dark Knight and Inception, you can see that Interstellar suffers not from a lack of ambition (its ambition is its greatest asset), but from some occasionally faulty execution in a few key moments. For all of his clinical precision, Nolan needed to follow the lesson of his movie and let go. He didn’t need to handhold the audience on explaining how love works or how we can quantify a father-daughter connection (when Morgan tells Tony Stark “I love you 3000”, she’s not speaking in particular units). Interstellar has it largely right even in its bleak view that Earth must be abandoned if humanity is to continue. Its grasp of the heavens is second-to-none. Where the film falters is in how we relate to each other and why not everything needs to be perfectly precise.

Tomorrow: Dunkirk

If you missed my previous articles on Nolan's other films, click here.