Although much has been written about the slapstick antics and the spatialized modernity of the films of Jacques Tati, it is essential to draw a direct line between the physical humor that Tati’s Monsieur Hulot expresses and the joke-filled structures of the commercial buildings and homes in which M. Hulot finds himself. While M. Hulot bumbles through various scenarios in his signature trench coat, pipe, and angle fedora, Tati’s iconic character maintains a facial stoicism more akin to Buster Keaton than Charlie Chaplin, rendering him as a liminal figure closer to the comedic “straight man” than a vaudeville clown.

By rereading M. Hulot as the “straight man” in a comedic duo with the architectural spaces in which he finds himself, one can literally locate the role of the “funny man” within the architecture itself, as the buildings provide the jokes and gags about which M. Hulot subtly reacts. Through the juxtaposition of M. Hulot’s labyrinthine Parisian house and his sister’s hyper-modern home in Mon Oncle as well as the almost dystopian office buildings and Chaplin-esque French bistro in Playtime, reframing Jacques Tati and the architectural work of his production designers as a uniquely successful comedic duo in mid-century cinema is necessary for gaining a more complete understanding of the late auteur’s filmography.

Straddling the line between the warm textures of traditional French architecture and the austerity of space age mod design, Jacques Tati’s heartwarming family film Mon Oncle expertly unravels the generational tensions that pervaded French cinema in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Although Tati fell into the category of a generation of classical French filmmaking in terms of narrative progression and audiovisual language, his complete control of the cinematic craft and acute awareness of comedy as a mechanism for sociopolitical satire placed him in a positive light amongst the burgeoning New Wave filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, affording him the dual relevance as a chief entertainer amongst the French populace and as a pioneer of the new director-centric cinema. Pivoting from the Chaplin-style expressionism of his earlier hits like Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday into a space of Keaton-esque comedic stoicism, Mon Oncle sees the tensions of Parisian modernity playing jokes on Tati’s M. Hulot rather than Tati creating the jokes directly.

In order to address this shift towards a passive “straight man”-style slapstick, it is essential to acknowledge the role of comedic spaces within the film, particularly M. Hulot’s M.C. Escher-like home and the now-iconic Villa Arpel. After a charming sequence showcasing the small neighborhood surrounding M. Hulot’s old-style apartment building, a long shot reveals the maze-like trek that the protagonist must endure to arrive at his top floor apartment. While M. Hulot remains stoic along his slow walk along windowed hallways and exterior corridors, the clunky design of the old building imbues the scene with humor by dragging out M. Hulot’s return to his small balconied studio, rendering the architecture as the overt comedic force in the sequence.

Similarly, when M. Hulot visits his sister and her family at Villa Arpel, the contrast of Tati’s old-fashioned protagonist and the hyper-modernism of the geometric homestead craft a dueling style of humor similar to the “straight man, funny-man” system that defined silent-era vaudeville. From the unpredictable spitting fish fountain at the center of the garden to bouncing glassware and automated machinery in the kitchen, Tati ties the humor of Villa Arpel directly to the cold and calculated nature of the house’s mid-century futurism. Ironically, the only individual who seems equally disconnected to the boxy, almost Lego-like home is M. Hulot’s nephew Gérard, who finds new joy with his uncle through bike riding, pranking, and other forms of play beyond his parents’ mod lifestyle. While earlier films like Chaplin’s Modern Times addressed similar issues of the coldness of capitalistic futurism and the complications of possible progress through factory machinery and department stores, Mon Oncle sees the problems of modernization make their way into the home, examining the anxieties of technological advancement through humorous interactions and accidents in the “house of the future.”

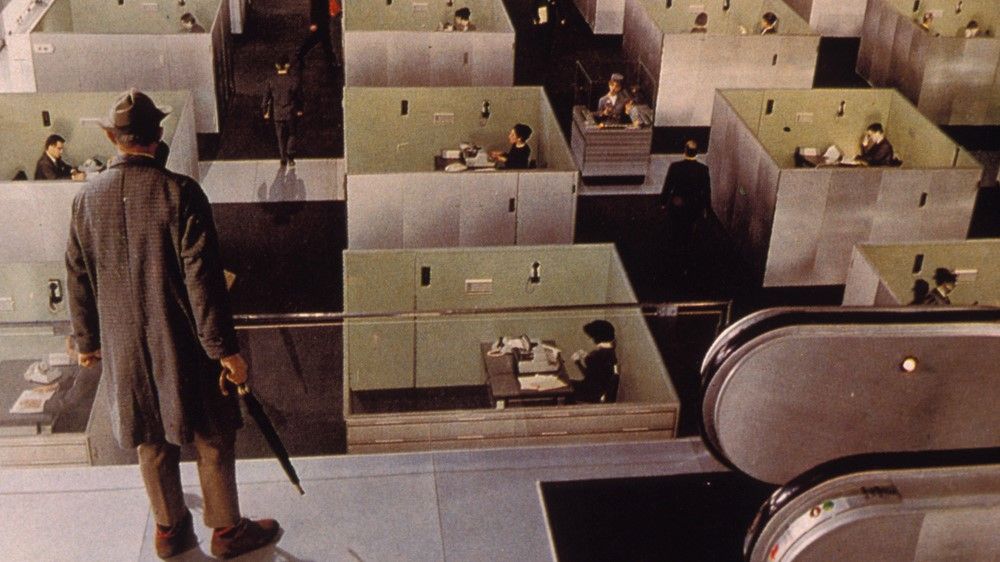

Expanding beyond the funny interpretation of futuristic fears that plague familial spaces in Mon Oncle, Tati’s extravagant masterpiece Playtime sees the rigid solemnity of consumerist “progress” overtake all of Paris through his titanic “Tativille,” a feat of epic set-design that contributed to the financial downfall of his career. Creating actual oversized box-like buildings of steel and glass, the offices and technological exhibition at the center of Playtime transform the impersonal modern architecture into an imperceptible yet often hilarious dystopia. From lengthy gags on elevators, escalators, and mirror-like corridors of cubicles in the office park to zany technologies and goofy gadgets at the World’s Fair-like expo, M. Hulot’s “straight man” role becomes even more passive and observational amongst the aspects of futuristic absurdism, culminating in a colossal collection of cars swirling endlessly around a roundabout in the film’s conclusion.

While Mon Oncle dips its toes into satire within the framework of a family film, Playtime dives into the deep end of sociocultural, bringing M. Hulot along for every humorous expression of the dystopian systems throughout the film. Capitalizing on the gags of seemingly endless and similar looking spaces as well as the symphony of disconnection and missed connections in climactic restaurant sequences, Playtime prioritizes the direct comedy of spatial interaction more than any other film in Tati’s body of work, establishing a new architecture of comedy based upon the disillusionment of perceived progress.

While Playtime’s puckish prescience operated in conjunction with the film going over-schedule and over budget to nearly tank Tati’s career, the near-prophetic humor and layers of satirical wisdom at the center of the film have allowed Playtime to settle neatly into the comedic canon. Although it is essential to acknowledge the role that Tati’s signature protagonist plays in functioning as an entry point into his culturally critical comedies like Mon Oncle and Playtime, the true power of his comedic touch falls in line with the locations in which he places M. Hulot. Both Mon Oncle and Playtime brilliantly revitalized the silent-era slapstick antics of the “straight man” by contrasting them with the “funny man” structure of performative places like Villa Arpel and “Tativille.”