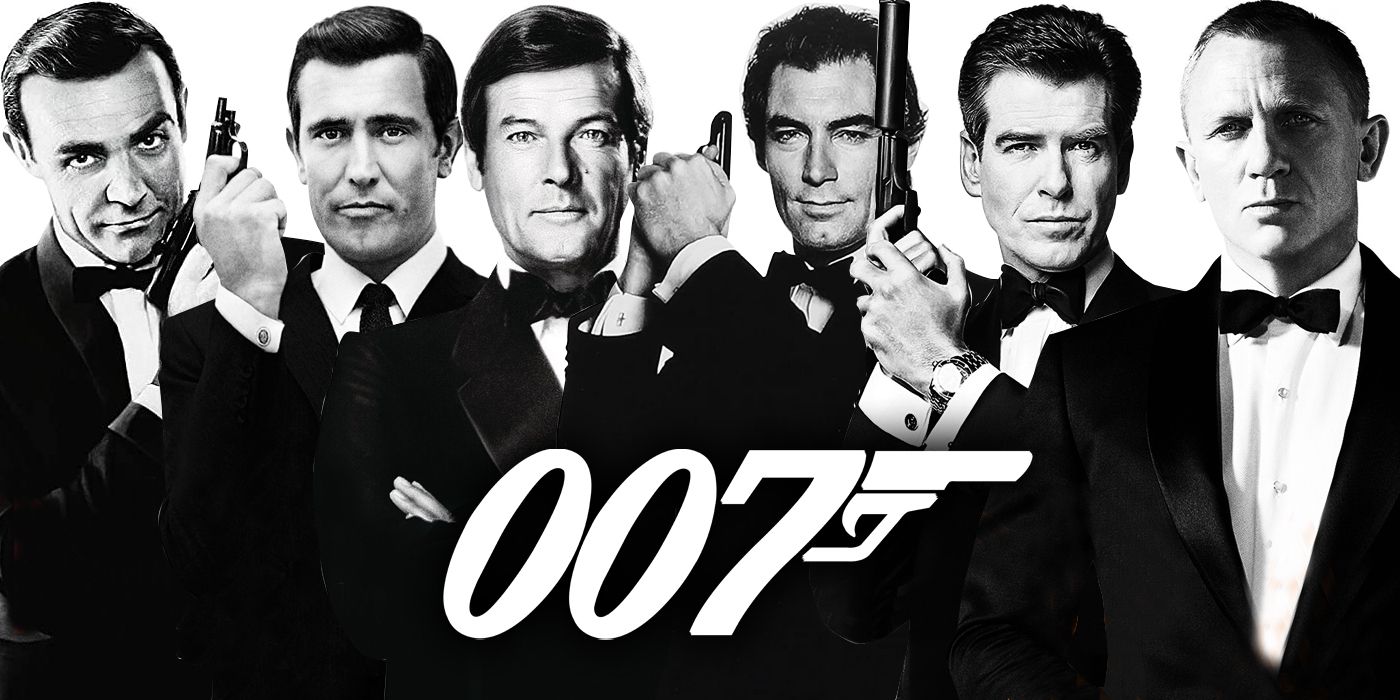

The James Bond franchise remains one of the longest-running franchises in film history. Over the course of over 50 years, it has cast six actors in the lead role and tried to navigate the shifting demands of global culture and Hollywood trends. We all have a vague idea of what constitutes a James Bond movie, but a closer inspection reveals a prism of ideas where not even the producers seem entirely certain about what a James Bond movie should be. We know about the girls, gadgets, cars, and villains, but what about the secret agent at the center of it all? How does Bond change with the world?

After watching all 24 James Bond movies from EON Productions (i.e. the "official" James Bond movies), I've broken down how each actor defined their particular tenure as Bond and the legacy of that performance.

Sean Connery (1962 – 1967, 1971), The Original

Sean Connery defined James Bond in the popular consciousness for better and worse. When most people think of James Bond, they don't think of the character from Ian Fleming's novels. They think of Connery, the first actor to play the role and the one who basically crafted our idea of what Bond is and isn't. For Connery, Bond is debonair, wry, and charmingly aloof. He's basically a power fantasy of the 1960s male. He wins every fight, gets every girl (the only "women" in the world of Connery's Bond are stern matrons working for Blofeld; every other person without a "Y" chromosome is a sexual object for Bond to conquer), and always has a quip at the ready.

Because Connery left such an impact on the character, he is cited as the "best" Bond, but I would challenge that Connery, while a pretty good actor, is left adrift by a bad, boring character who simply doesn't hold up to modern-day scrutiny. Even if you leave Bond's misogyny behind and overlook the racism of the times that permeates the movies (Bond's "transformation" into a Japanese man in You Only Live Twice is particularly cringeworthy), what you have is fairly shallow character who lacks substance. Bond never questions his missions or his relationship to women or anything. He has no inner life and so the fantasy he presents ultimately wears thin, especially after six movies. And to be fair, maybe that's the purpose of Bond: to be a blank slate that frustrated men can project themselves onto where they live out a fantasy of saving the world and then having sex with gorgeous women who conveniently die five minutes after you sleep with them.

Yes, Sean Connery is the quintessential Bond, but I'm grateful that the franchise found a way to grow beyond him even though it could only do so in fits and starts because of his outsized impact on the role. Granted, Bond is a product not only of actors, but also of the time when the movies were made. Nevertheless, watching Connery's six Bond movies, I couldn't help but lose interest in the hero and wonder why he had become such a cultural phenomenon beyond an outdated representation of male power that at best today plays as ironically comforting and at worst as retrograde and dull.

George Lazenby (1969), The Outlier

George Lazenby has the rare distinction of only playing James Bond once. A car salesman from Australia who became a male model, Lazenby basically bullshitted his way into the role, which is charming in its own right (for more on Lazenby's story, you can watch the amusing documentary Becoming Bond on Hulu). Lazenby took on the role for On Her Majesty's Secret Service, and while Lazenby may be a punchline for how he's the "unknown" Bond, he ultimately was in one of the best Bond movies.

On Her Majesty's Secret Service is a Bond film that, while beset with problems endemic to other early films in the franchise such as pacing and plotting, is clearly trying to do something different with its narrative and with Bond as a character. In place of Connery's aloofness, you have Lazenby clearly having a blast with the role. He genuinely seems to enjoy playing James Bond, but also discards the coldness in favor of vulnerability and genuine connection with other actors (when Tracy is upset and he asks her if she wants to talk about it, I was gobsmacked—Bond wanting to talk with a woman instead of just bedding her!). What Lazenby brings to the role is keeping the action, sex, and espionage but showing a Bond who genuinely wants things and is willing to sacrifice to make it happen. Of course, the film can't go more than five minutes without him being officially a spy so his resignation is quickly rejected, but Bond makes it clear that his priorities are stopping Blofled (Terry Savalas) and saving Tracy (Diana Rigg).

And where does OHMSS end? In tragedy! Blofled lives and guns down Bond and Tracy on their marriage day, and while Bond survives, Tracy dies and he mourns her! For a character who could literally have women die in his bed (RIP Jill Masterson and Aki) and then moved on without a second thought, Bond's grief adds depth and personality to the character. Unfortunately, Bond reverts back to his old ways when Lazenby leaves the role and Connery reprises it in Diamonds Are Forever, but for one brief film, we get a glimpse of 007 being more than a sex-and-action delivery vehicle.

Roger Moore (1973 – 1985), The Senior

Roger Moore was already 45 when he signed on to play James Bond in Live and Let Die. He would play the role for six more movies, making him the actor with the most Bond movies to his credit (technically Sean Connery is tied if you count the unofficial Thunderball remake Never Say Never Again, but I don't). When he finally hung up his Walther PPK in 1985, Moore was 57 years old, far too old to play Bond, and a sign that producers Albert R. Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson never really knew what to do with him as an actor or with the Bond character.

I understand that some people have a soft spot for Moore, and at his best, he brings a cheeky affability to Bond. Moore is James Bond at his most inoffensive, but this also makes him Bond at his most forgettable. Moore leaves a stamp on the role not through memorable choices or terrific movies but through sheer longevity. He kicked around on this role for a while and you can see the films around him shifting to meet both the times and the whims of anyone who had an idea they wanted to toss into the latest script.

Because there's no consistency in Moore's movies beyond "Bond, girls, gadgets, and a villain with a convoluted plan", Bond doesn't really matter. He doesn't have a character arc or even emotions. He grins his way from exotic setting to exotic setting, sleeps with women whether it makes sense for him to do so or not, and saves the world by disarming the whatever device and killing the bad guy. This emphasis on the outline of Bond—an empty vessel for sex and action—robs the Moore era of any specificity. Instead, it's just a series of chasing trends (Live and Let Die is blaxsploitation, The Man with the Golden Gun is kung fu movies, Moonraker is Star Wars, etc.) and failing to make the case about why we should care about Bond other than he's become an institution.

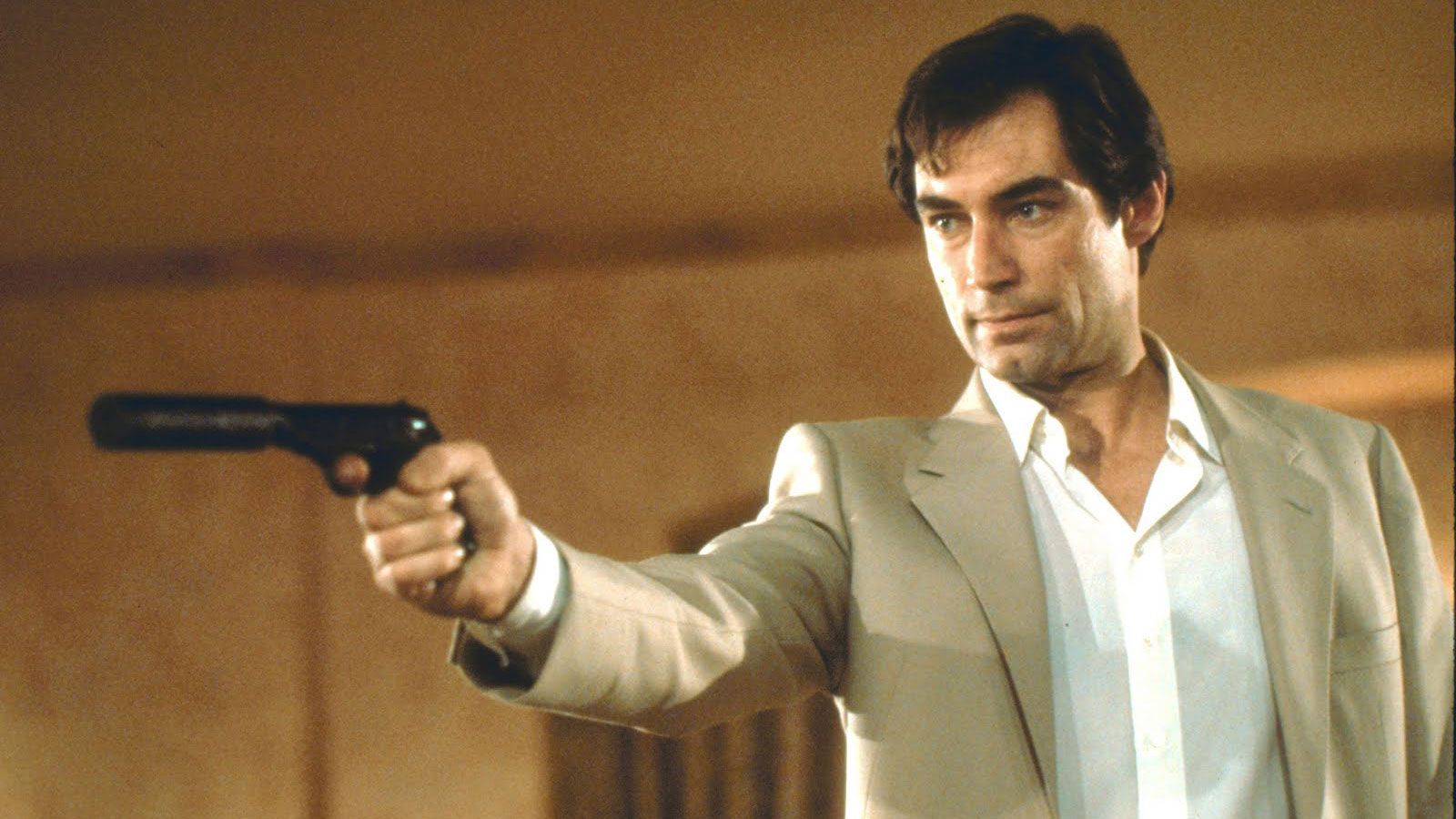

Timothy Dalton (1987 – 1989), The Rogue

Timothy Dalton's Bond movies, The Living Daylights and License to Kill, are fascinating oddities in the Bond franchise. After trudging along with overly goofy crap in the Moore movies, Dalton's films go for not only a harder edge, but also feel far more streamlined. There's less emphasis on the villain and his many goons and his convoluted plan (although that kind of starts rearing its head in License to Kill). Instead, the movies keep the emphasis on Bond and what he's going to do, and in these two movies, he's not just the debonair charmer we've seen in past iterations. While "realism" may be a stretch, the Dalton Bond is a more stripped-down action hero where his romancing of women is perfunctory and secondary to his action chops.

There are times when the Dalton Bond movies don't even necessarily feel like Bond movies, and that makes them incredibly interesting. As you make your way through the first hour of License to Kill, you find yourself wondering if this action story really needs Bond, and then you're forced to ask, "What makes Bond, well, James Bond?" If you strip away British Intelligence and his gadgets and the women, what do you have? The second half of the movie then reasserts all these things (Q just randomly shows up with a case full of new toys), but for a time, you're seeing Bond in a new light, and you get that as well in The Living Daylights. It also helps that the villains are grounded in the reality of arms dealers (Whitaker) or drug kingpin (Sanchez) rather than the fantastical stuff of the Moore movies like space lasers (Moonraker) or Russian agents teaming up with jewel thieves (Octopussy).

At best, it feels like the Dalton Bond movies are laying the groundwork for what happens with Daniel Craig. If Pierce Brosnan is an attempt to reclaim the past by pairing a debonair Bond with a more modern angle, then Dalton is there trying to inject a harder-edged personality into the character. He doesn't always get there, but you buy him as a person with a code and a willingness to do some ugly things to accomplish the mission. That's really the tug-of-war at the heart of the James Bond character: who wants to make him just a checklist of behaviors and who wants to treat him like a person. Dalton only got two Bond movies, but like the other short-lived Bond, George Lazenby, he left his mark on the character.

Pierce Brosnan (1995 – 2002), The Wasted

GoldenEye might be the most frustrating film when viewed with the knowledge that it would be the only good Bond movie Pierce Brosnan ever got to his credit during his time as 007. GoldenEye feels like the right film at the right time for the character as it begins to reappraise and critique Bond in a post-Cold War setting. One of the film's best moments is when Bond is walking through the ruins of Soviet Russia and he's just as much a relic as the fallen statues around him. There's an interesting trajectory here, and Brosnan seems well suited to go on that course. And then the producers never follow through.

Brosnan is not the reason that Tomorrow Never Dies, The World Is Not Enough, and Die Another Day are bad movies. They each suffer from their own issues, and to Brosnan's credit, he does his best to dig into the character when the rare opportunity arises. But more often than not, Brosnan is trapped in the same problem that ensnared Moore in the 70s and early 80s, which is that he's burdened by bad scripts that care more about villains and/or tech than the main character. Brosnan is arguably in an even trickier position since there's no more Cold War and he has to handle a character who has been around for decades, played by four different actors before him.

And yet there's a whole air of missed opportunity with Brosnan. He has the acting chops as seen in films like The Matador and The Ghost Writer, but the majority of his Bond movies never give him a workable character. The closest you get is something like The World Is Not Enough and his feelings for Elektra King (Sophie Marceau), but then the writers, producers, and directors force him back into a series of tired markers, so Brosnan goes through the motions of saying "Bond. James Bond," and "Shaken, not stirred" as if the character is nothing more than his trappings. GoldenEye showed they had the right direction and the right actor for a new era of Bond, and the producers whiffed.

Daniel Craig (2006 – 2020), The Soulful

It took almost 50 years for the Bond franchise to give its main character a soul. For most of the character's life on screen, he was a male power fantasy: a guy who gets the sexiest women, drives the fattest cars, has the best toys, and saves the world. This power fantasy could not be disrupted, so the character's air of invulnerability could never be penetrated. He was a superhero without the superpowers, and a human without the humanity. As a light distraction, that was all well and good, but as action movies and spy movies changed (most notably, the Bourne franchise presenting a real challenge to Bond), Bond had to change with it, and Craig was the perfect vehicle for that change.

Movies like Casino Royale and Skyfall ask is, "Does James Bond have a soul?" They make no bones about him being an assassin and a particularly cold-blooded one at that, so is there any humanity in him? Craig, with his soulful, vulnerable performance masked by steely resolve turns Bond into a real, flesh-and-blood person in a way that none of his predecessors could. Part of that speaks to Craig's acting range and what's demanded of a leading man in the 21st century, but part of it is what the producers know about action films in a post-Bourne world. It's not enough to give a one-liner, a smirk, and a shot anymore. Audiences demand more, and Craig's Bond provides it.

He's also the only Bond that knows he has to hold relationships on screen. Craig is an actor who knows how to balance holding the screen with reacting to his co-stars, so you get incredibly strong dynamics on screen. It's not The James Bond Show Starring James Bond; it's how he reacts to Vesper Lynd (Eva Green), M (Judi Dench), Moneypenny (Naomie Harris), and more. Craig manages the difficult balance of making Bond superhuman when he needs to be, but, more importantly, knowing when to make him human.