Don't you just love movies that defy description? British director Nicolas Roeg sure was good at making movies like that for a while. Some of them go off the rails and collapse under the weight of their own oddball vision (The Man Who Fell To Earth and Eureka come to mind), but even then there is something compelling, even hypnotic about them. Roeg enjoys going to raw, often forbidden places and until his later efforts pushed too hard on the taboo meter and began to lose their relevance (Castaway, Track 29, Cold Heaven), Nic was on a roll. There was Performance (co-directed with Donald Cammell), Don't Look Now (reviewed in this here column), The Man Who Fell To Earth and Bad Timing, along with the second film in this chronology and his first as solely credited director, Walkabout.

The film is loosely based on a book by James Vance Marshall about a young American brother and sister who must rely on an Aborigine boy when they are lost in the Australian outback. Roeg and his screenwriter Edward Bond take this basic premise, change the siblings to English schoolchildren, and twist it into a meditation on suburban alienation, denial of sexuality, British entitlement and the utter loss of connection between humans and the natural environment (not to mention between humans themselves). Taking place almost entirely in the desert and stunningly photographed by Roeg (a director of photography who shot Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451 and worked the second unit on Lawrence of Arabia), Walkabout achieves a kind of cinematic poetry with its meditative pace and strange, off-kilter vibe. Almost every frame could be discussed in terms of its density of meaning (some might accuse Roeg of heavy-handedness for this very reason; I prefer to take the viewpoint that driving things home is a dirty job but someone's got to do it).

Right from its early images, the film is asking us to consider larger issues.  The brother and sister (Jenny Agutter and Lucien John [actually a young Luc Roeg, the director's son]) swim in an apartment building pool right next to a vast expanse of natural ocean. Their mother prepares lunch while listening to a radio cooking show describing how a bird used in gourmet cooking is fattened and drowned. The boy walks through a park in which all the tree names are clearly labeled (a not uncommon practice, of course, but one which takes on a new meaning in a film about how nature is appropriated by mankind). There is also the haunting image of an entire class of girls doing breathing lessons, inhaling and exhaling in a creepy rhythm that, again, evokes the idea of how the modern world sees fit to teach us even to breathe.

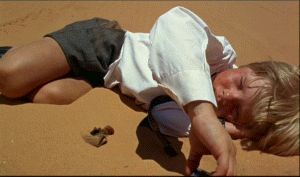

When the father of the boy and girl takes them for a picnic lunch in the barren outback, he has a little bit of a meltdown (to say more would deprive first-time viewers of one of the great shocking, disorienting scenes of modern film) that leads to the kids having to go off on their own. They wander for days, becoming more and more dehydrated and desperate, all the while exchanging perfectly meaningless banter about societal proprieties like keeping one's blazer clean.  Indeed, words mean little in such circumstances, an idea that is more fully explored once the Aborigine (terrific David Gulpilil) appears to help them. "We need water to drink," the girl pleads, frustrated that not everyone can understand English. "I can't put it any simpler." But her brother can, making a glug-glug sound instantly recognizable to anyone as the need for some liquid refreshment. Off they go on their journey together, then, with the Aborigine's clear but respectful affection for the girl increasing, only to build to a heartbreaking moment when she reduces him to the role of a servant. This, combined with his seeing men hunting for sport for the first time, sends the Aborigine boy into an unbearable world of heartbreak.

Along the way, Roeg punctuates the young people's trek with some of his patented dramatic cross cuts, such as the Aborigine using every part of the kangaroo he has killed to help the trio survive, while a butcher chops and grinds kangaroo meat for supermarket consumption. Sex and death are intertwined as the girl swims nude in a pond while the Aborigine boy spears fish for dinner. The brother's beloved radio is on almost constantly, and it is another thematic element, as tinny voices from the developed world and its self-important concerns provide thoughtful counterpoints to the odyssey in the barren desert.  Twice Roeg cuts to other signs of so-called civilization taking place not far at all from the lost brother and sister. One, a weather balloon station, where the men go nuts for the slightest glimpse of stocking from their only female co-worker; and the other a soul-sucking labor camp where young indigenous people make plaster kangaroo souvenirs for tourists. A continuing thread running through the fabric of this film is the notion that the privileged classes not only know nothing of nature, but also remain closed off to what it may have to teach them. Agutter's young girl seems to learn nothing from her adventure, although her younger, more open brother has learned to implement rudimentary ways to talk to the Aborigine and even goes along with him on the hunt.

The devastating ending of this film is not only due to the tragic circumstances surrounding the girl and the Aborigine boy, but to the double-whammy epilogue which shows the siblings' return to an uptight and uncaring township and a flash-forward to the girl, older and entrenched in the rat race, holding onto a rose-colored memory of her time in the outback, imbuing it with an understanding she never had at the time. Finally, there is John Barry's gorgeous score, which features timeless orchestrations along with a children's choir and even spoken word. Also be ready for the vintage Rod Stewart song that makes a memorably symbolic appearance.

Unforgettable and still groundbreaking, Walkabout is one for the ages.

James Napoli is an author, filmmaker and teacher whose third book Violation! The Ultimate Ticket Book is now available.