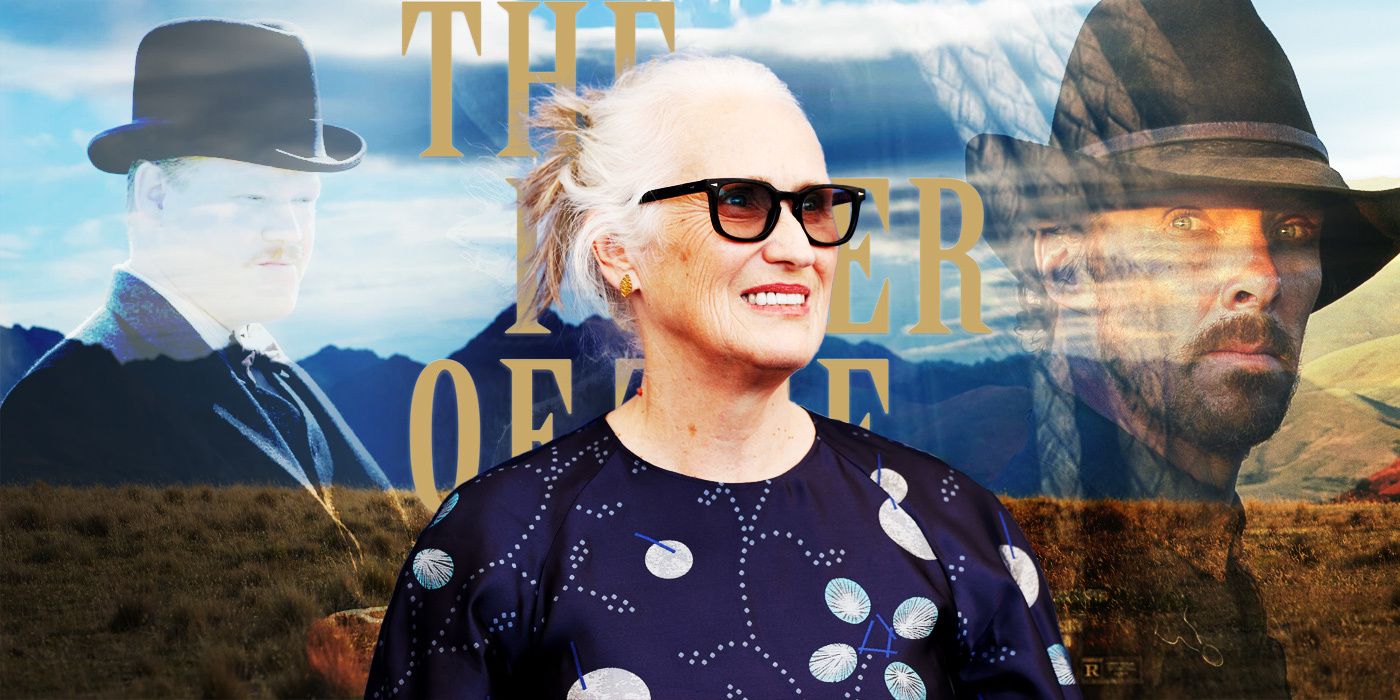

New Zealand native Jane Campion is a staple in the history of modern cinema, being the first woman to win the prestigious Palme D'Or at Cannes Film Festival along with scoring Academy Awards for her film The Piano such as Best Original Screenplay and Best Director in 1993. Her work has transcended genres with romance films like Bright Star and a gritty Western starring Kirsten Dunst (The Virgin Suicides) and Benedict Cumberbatch (Doctor Strange), The Power of the Dog. Campion's filmography heavily centers around women's lives and roles within a heavily masculine environment. Whether it's Elizabeth Moss's character in Top of the Lake as one of the few female detectives solving the crime of missing girls or Dunst's role of a mother in 1920s Montana, Campion's work is heavily influenced by topics of gender and sex.

According to film scholar Laura Mulvey, the "male gaze" is defined by the viewing experience of films centered around male pleasure and point of view as per her article "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." Cinema's history and visual composition, according to Mulvey, is shaped by a voyeuristic way of scrutinizing, meant to cater to the male perspective. This is especially significant in how female bodies are conveyed through the camera apparatus. In doing so, the framing cloaks every image in its inherent masculine point of view, as Mulvey suggests. So, that raises the question: can there be a "female gaze" to counteract its current one? The "male gaze"? Or can the auteur's ability to frame bodies, female or male, change this perspective? Where does the gender of the auteur come into play? Or, is the inherent use of the camera by someone like Jane Campion challenging the institutional sanctions of the "male gaze" merely by creating new views and frames? Posing these questions alone suggests a myriad of dynamics at play here. Layered on top of one another as the "male gaze" itself contains multitudes.

Jane Campion challenges the "male gaze" in a way that's not reactionary nor assertive. It doesn't necessarily make it any "better" but, instead, makes it innovative. A new lens through which to look. Instead, she chooses to react to the "male gaze" through sensuality, specifically framing the male body throughout her work and coating it in appreciation. From Harvey Keitel in The Piano, to most recently The Power of the Dog, there's a level of love and care that comes from Campion's specific way of gazing at male bodies that depicts a new way of interacting with the camera and showcasing the gaze itself through the eyes of a female director.

It's not about retaliation for the inherently violent and voyeuristic way the "male gaze" operates in the history of cinema. Campion's counterbalance for the "male gaze" seems to steam from appreciation and care. Her work is tenderness as her camera tracks the male form with a slow appreciation that is not leering. It is for the view of women but not necessarily for "pleasure" in sexual connotations, but for the sake of love. Pleasure is derived from love and, therefore, care otherwise lacking in the "male gaze" that dominates cinema. In doing so, Campion anchors her feminine touch in each scene and layer. Her bodies become more than just "bodies" on-screen, shedding their clothes to be leered at but be gazed at like beautiful status in a museum. There's an appreciation to her shots and framing that draws viewers in to almost participate, as opposed instead of at a distance.

While the idea of a "voyeuristic" gaze isn't necessarily useless in a cinematic capacity, it has become a tool of violence used against femininity on screen. It's been the source of pleasure in direct connection to violence that most films have adapted to and therefore become an integral part of the "male gaze." Campion, however, reinvents the voyeuristic aspect of the "male gaze" and turns it more into a soft caress that graces the objects on the screen. Tenderly tracking their movements, especially once nude bodies come into a scene. It also permeates all through the scene, with the way a lot of her shots are used with natural lighting and outdoors. Connecting her characters to the nature that surrounds them—grounding them to the atmosphere and earth, instead of having them own the space.

In one particular scene during The Power of the Dog, Cumberbatch's character lies out in an open field under the sun. Fully nude, his character begins to slowly drag an old handkerchief that once belonged to his mentor and implied lover, Bronco Henry. The shot utilizes the handkerchief like a tool of sensuality as Cumberbatch sweeps it over his face and body as if it were Henry's hand caressing him. The camera zooms in to a profile of Cumberbatch as this happens and, the sun only bathes his face and body in warmth. Making him look like a moving picture. Beautiful, sensual, and enthralling. It's a gaze that invites instead of limiting viewers to just male pleasure. It's a pleasure that becomes universal as Cumberbatch's body is splayed out for its beauty and pose—channeling or recalling old paintings of bodies in the nude.

Shots like those in The Power of the Dog extend across Campion's body of work. She is always connected with nature, letting her characters exist in their natural states as the camera only captures their essence. Unlike the "male gaze," Campion's response to it is not to punish or repel. Her response is to alter its course of action and grant it an even higher level of intimacy that invites all viewers despite gender. It's not about counterbalancing the gaze with the same components but only women, but taking the gaze and extending its capacities to something beyond gender. Scenes like the one in The Power of the Dog have the potential to reinvent and redefine the "male gaze" to serve a universal lens. One that fits any gender, sexuality, or both. Perhaps even consider the way the "male gaze" can better serve an ethical way of looking at the world around us instead of perpetuating violence and deriving time it and time again.