Steven Spielberg is a legendary filmmaker, and for over two decades now he’s been working with the same cinematographer on every film: Janusz Kaminski. The Polish DP’s first collaboration with Spielberg was on 1993’s Schindler’s List, and it’s been a match made in heaven ever since. Kaminski’s use of bold light has resulted in iconic imagery in films ranging from Minority Report to Catch Me If You Can to War of the Worlds, and he’s showed off his dynamism shooting non-Spielberg films like The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and The Judge, as well as the Lady Gaga music video for “Alejandro.”

Kaminski has a knack for striking lighting choices and cinematography that traffics in visual metaphor, and that’s certainly the case with his latest film The Post, another collaboration with Spielberg. This grounded period drama is essentially a series of scenes that involve people talking in rooms, but Kaminski finds ways to keep the frame engaging while also reinforcing story, character, and theme through composition and lighting choices. It’s not as flashy as something like A.I. Artificial Intelligence, but Kaminski approaches the scenes in The Post with the same meticulousness and eye for beauty, going so far as to capture dialogue scenes with the intensity of a big action set piece.

With The Post expanding into theaters nationwide on January 12th, I recently got the chance to speak with Kaminski about his work on the film. As a longtime fan of Kaminski’s work and admirer of what he was able to capture in The Post, I jumped at the opportunity, and the result was a wide-ranging, insightful, and refreshingly candid conversation with one of the most interesting cinematographers working today.

During the course of the interview, Kaminski talked about the speed with which The Post came together, how he approached the material, and the limitations of shooting in a real office building. He also went in depth on his working relationship with Spielberg and the staging of a scene towards the end of the film, and he teased his work on Ready Player One and what it’s like to collaborate on scenes set in a digital world. Kaminski also discussed his philosophy on lighting at length as well as the current state of cinematography, and he kindly indulged me in talking about a specific scene from Catch Me If You Can that is straight-up gorgeous.

It was a delightful chat that I could have continued for many, many more hours, and I do think you’ll find what Kaminski has to say about the art of cinematography fascinating. He also, of course, provides insight into what it’s like to collaborate with someone like Steven Spielberg. Check out the full interview below.

I know that this came together quite fast, and I believe you and Steven were preparing a different movie at the time, The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara, or getting ready to, so I was kind of curious, what was it like to jump into this project so quickly?

JANUSZ KAMINSKI: Well, Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara was still in the early stage of casting. We scouted the movie last summer, but you know the conundrum of finding the boy was always the primary deterrent and as he was looking for the right actor, he got this offer from Fox to read a script and the movie was almost set up and Steven read the script and he fell in love with it, and he immediately hired Josh Singer to do a little bit of a rewrite. I think Meryl might have been already in some kind of early negotiations to do the movie. And he brought an amazing cast with him and we got into production. He's a very, very productive man. He doesn't waste time on unnecessary talks. It's straight to the point. He knows exactly what he wants in terms of the coverage.

You know what he wants in terms of the performance, so at the top of it, he really doesn't have to deal with anyone's demands for additional coverage or rewrites to accommodate some young executive’s notes. There are no notes. He's the one who makes notes. So he's in a sense the auteur. He's making the movie he wants to make. Subsequently, he's able to make them really, really fast in terms of pre-production. It's not a complicated movie from my point of view to make. It was harder for Rick Carter at the art department simply because the schedule dictated that the production was going to be centered around major locations that were part of the movie. So we're filming in White Plains, because that's where we got the office building that we could build our set inside, then other locations of White Plains, to facilitate the story of The Post. Fortunately, White Plains has really great architecture that resembles some of the architecture in DC. It's kind of brutalistic, rather grub, but I find it to be really beautiful architecture, so we were able to do several additional locations in White Plains.

Then, we went to Manhattan and we grouped our locations in Manhattan. We used 7th Street in Manhattan to perform as Manhattan. Then we used some locations to perform as Washington D.C. Moviemaking to some degree is such a well organized machine. We go build those sets, like Ready Player One, we're building those sets that are 200 feet tall, you know, layered with trailers sitting on the top of each other. And we've got people acting on those trailers and nothing happens. So, you know, moviemaking is efficient operation conducted by people who are really great at it.

I’m always curious about the early stages. So, when this project was a go, when Steven said it was his next movie, what were those first conversations with him like about the visual approach to the movie? Did you guys have a specific idea in your head right off the bat?

KAMINSKI: No we don't do that. We don't do that. The conversations are really clear about the locations and the sets and Rick Carter at this point. The decision has to be made very fast in terms of Steven wanting to make the movie because Rick Carter needed a certain amount of time to build the office, you know? We need to have it right away. Otherwise, we wouldn't make the deadline. I think Rick might have started even before the movie was fully greenlit. So that Washington Post floor was the most essential part of making the movie from the technical aspect of the movie. Locations and the story dictate the visuals. Knowing that I'm filming on an existing location, meaning that it was taking over an office building in White Plains, that we’re on the 26th and 27th floor, there's no equipment that allows me to bring the lights to the windows because it's so high.

Also, the reality of the movie is such that they did exist and live and work in the brightly, fluorescent-lit workspace, so the necessity of location prevents me from altering what the light might have been there. Consequently, we put our own light. We took existing fixtures and put our own ceiling and put our own color-correct and lights that we could alter the color and brightness. But essentially, the movie was lit from the ceiling fixtures with occasional supplements from softer sources from outside the frame. But as you know, as you've seen the movie, some of the shots are very complicated, where we see the entire floor. So, that approach made it look realistic, slightly gritty, within the confinements of the story and easy for Steven to move the camera any direction he wanted to.

Well, I think that's one of the things that's really great about the movie. The reality is, there's only so much you can do with a newsroom to make it look compelling and dynamic without taking away from the characters. So was that challenging for you in terms of you have this floor and there are only a certain amount of ways that you can actually shoot and light it to make it look interesting on screen?

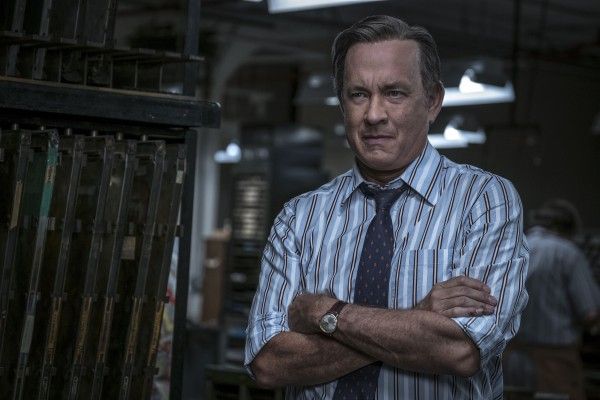

KAMINSKI: I did. Particularly with the scene with Bob Odenkirk and Jesse Plemons that takes place at night. So you take a liberty to say, "Okay they work through the night, how do you bring the night?" You make the windows darker and then you do some of the lights. But really if this is a more dramatic filmed movie—I’ve done that in other movies where, you know, you’re in the office building and you turn lights off and you put, particularly Tom Hanks in Catch Me If You Can, he's sitting in the FBI office, it's completely dark except for one little lamp. You know, it was a different movie.

In this movie I could alter some of the density of the light but it still had to represent the reality of what the journalists and newspaper's floor looked like, even at midnight. So I took some liberties. I already took some lights off, made it slightly bluer, slightly cooler, because it was good for the confrontation for Jesse and Bob. One could have pushed a little bit harder, but my aim was to stay not as stylized. Be really, really, really subtle with my work, and that style also was embracing Steven's work as a director. They always serve the story. We don't have major camera moves. We don't have the flashiness in terms of storytelling that we normally do, simply because we wanted to stay as honest to the story, as honest to the performance, and be respectful too, of what the story tells us and how relevant it is to a modern America.

There’s no explosions, there's no big set pieces, but one of my favorite shots in the movie, towards the end, features a bunch of men huddled around a table while Kay is carefully considering a decision. And that plays out with the tension and the thrills of a big action set piece. I was wondering if you could talk about how that shot came together and the blocking and staging of it, because I think it's really terrific.

KAMINSKI: You know there is a painter who Steven loves. He owns several paintings by him. He was considered to be more of an illustrator when he was doing illustrations—the name will come to me later but maybe too late. But you know there are several images that Steven has of this painter and they're always very—men caught in the moment of importance. So we didn't use that painting as the blueprint but there is a certain aesthetic that Steven has and we don't fight our aesthetics, you know, and Steven's aesthetics are such that like, shot of relevance. So you have Kay sitting at the desk with men huddling around and there's a conversation with Kay and Tracy Letts. There's this tremendous sense of importance and a little secrecy. What are these men talking about? It must be important because they all huddle in their little group and it feels a little spacey at first, but you forget that really quickly because of the significance of what they're saying.

It was a great way to space the scene because the content was so important. It's woman against men and men are standing. It’s not really even the men against the woman, it's the attitude of that particular time period. Men were in the condition of decision-making and women were always subservient to the men and often, if not always, serving position to support the men and make the men better in terms of facilitating the needs of the men. In this case, Kay is making the choice, very strong choice, by saying, "This is not your paper, this is my paper and this paper in fact is not even my paper. It belongs to the citizens and I'm going to make the decision I'm going to make." But before she makes that decision, there is a whole big, beautiful conversation. It's a straight, wide shot, as you stated. And it's really great because you see all the participants, not necessarily making the decision but being affected by the strength of Kay and her ability to not finally step up to her position, but making the choice to be less of a subservient or what's expected of her and become a stronger leader.

Consequently, she stands up and the rest of the dialogue is delivered with her standing, which means she's not in the lower position of the frame, she's equal to the man as a visual metaphor and now she's going to make a decision in terms of how she's going to conduct herself as an owner of the newspaper.

I love the visual storytelling in that shot and I've heard that Steven likes to feel out a scene on the day and likes to change things up, so I was curious what's that relationship like once you get on the set, once you get to a scene? Does he have storyboards that you guys are working off of?

KAMINSKI: No, there are no storyboards. Not on this movie. We never have storyboards on movies that deal with non-CGI or non-action subject matter. We only have storyboards for the visual tech department so we can budget the movie. Or, if it's an intricate action scene, there are storyboards so the stuntmen know what to create and the piece of equipment that has to be created to facilitate that. And, even with that, we follow the storyboard as a general blueprint but we really do not fully, fanatically follow what's in the storyboard he created three months before he makes the movie, because three months later he's got another idea.

So, no there's no storyboards. Yes, there is a process of altering the blocking and altering the placement of the actors and in this movie, because there are so many actors that practice was much more elaborate and it was great to see Steven working in his environment, working with all these great actors. Usually you get great actors who are less important. In this movie, you've got several really essential characters who need to be in the same frame, who need to be in the same shot because they represent different points of view. And they have power to alter how she thinks and what the decision making process will be for her. So it was great to see Steven morphing into yet another director, according to the needs of the script.

Something that's really prevalent in both your and Steven's work is these really strong, bold light sources, which can create these really beautiful shots. I was curious if you could talk a little bit about your approach to this kind of lighting.

KAMINSKI: I think light is essential storyteller. Obviously we all know it's part of everyday life as a psychological being. Void of light will make you suicidal. Countries that don't have daylight will expose citizens to artificial light to introduce happiness into their lives. I use light or void of light and shadows to tell the story and I have certain aesthetics. I like hard light. I like the light to be visible. I'm not the guy who's using flaccid light sources and underexposed the image and just uses so-called natural light. I use available light, every available light from the movie truck, but I like the light.

I think there is a tendency in modern storytelling to not use the light the right way. I think we're going to an extremely boring period in cinematography. I think the art of cinematography is disappearing. I think I for sure will make the statement that visual storytelling and visual metaphors are non-existent in most of the movies. People think that if you have it in focus and if you can see the actor you are a cinematographer. Wrong. They couldn't be more mistaken than that. So, I'm not trying to change the light. I'm just doing my thing and I like sunlight. I like sun coming through the windows. In this movie, I didn't do it as much, but I like to feel the light. I often will put the light sources in the frame, and because I like bigger stuff, I don't like the image to fall apart because I'm working with 35mm mega disc, it's a completely different beast. You don't have to create this softness, low, shallow depth of field for this imagery, simply because digital imagery is so unforgiving. And you can see everything and it looks artificial. It doesn't look realistic.

It’s not what I would do. So, they do the shallow depth of field. They put crystal shield in front of the lens, to alter the lens. I don't do that. I use straight lens, I use fielders occasionally and I use light and the light has a presence in the room. Or void of light. That's my storytelling.

One of the most beautiful shots that I’ve done in this movie is a very simple shot. Kay Grahame, she's in her office. She's dressed in this really beautiful blue dress. Her right hand is on her desk and she's looking towards the TV monitor where Dan Ellsberg is talking about what he has discovered and it's just this one beautiful soft light coming from the left side. And she's thinking. You don't need much. Just one light and just look straight. And believe me, if the light is reasonably bright, we're shooting at a healthy stop, we're not shooting at 1.4. We're shooting probably at 4. You know that kind of stop. I like that. I like sharp images. I like to decide when I want to go to shallow depth of field for the sake of storytelling and not to make things more interesting. Then another very difficult scene when Kay is talking to her daughter. They are reading the morning paper. It's a very formal composition with a window between two ladies. One is sitting on the couch, the other is sitting on the couch. Strong morning light coming in with a little bit of smoke.

To me, it's filming. I make movies. I don't make documentaries. To me, I'm making Hollywood movies. If I go make a low budget, independent movie like Diving Bell and the Butterfly, I can alter my ability to make the movie but will still feel the importance of visual storytelling. That's me, okay? So as you said, there are light sources, that's what I do. And when you look at the best cinematographers, not that I'm the best, but if you look at the significant cinematographers, they follow the same principle. There's some sense of reality with placing the light source in the frame and then motivating the artificial light, the direction of the light from the existing light source. If, in my opinion, that doesn't work for me, if it's not dramatic enough, I will create different lights that have nothing to do with reality for the sake of improving the movie, and the storytelling.

If you'll indulge me for a second, one shot of yours that I've always wanted to ask you about is in Catch Me If You Can. And I'm not sure if you'll remember it, but it's when Leo’s character is in the bar alone and has called Tom Hanks' character and you get this heartbreaking shot with these Christmas lights framing him at the bar.

KAMINSKI: Yes, yes. Tom is in the office floor of the FBI, he's sitting by himself. So they are both sitting in empty spaces. Tom is sitting in his FBI office. He's illuminated by a little table lamp. Leo is involved in a bar having drink by himself alone, empty, so there's two wide shots of two guys being lonely on Christmas night, they're just talking to each other simply because they developed this relationship. This almost paternal relationship between these two guys. And still lonely but yet very warm. They're saying "You can run but one day I'm going to catch you." I love that scene.

You create certain visuals that are appropriate for the scene. Yesterday, I went to some kind of a Q&A. We went to Sherman Oaks Galleria and this little bar. And the bar is kind of pathetic, but behind the bar there are windows and you're looking out at four or five and you’re seeing all this light twinkling behind you and we see the bottles of the light, of the car headlights and taillights is altered by the shape of the bottles, the alcohol bottles, and it looks so romantic, and you think, "My God, this is so romantic and lyrical, but yet such a sad location for someone to come in and have a drink because there is so much life outside. Yet sitting in this space that's relatively empty and not visually intriguing and there's so much more light outside." So you always look for those metaphors that layer the images and there's more to the storytelling than just seeing the actors and being in focus, you know?

I'm also really looking forward to Ready Player One and I was just curious what it was like working in that virtual space again and what you could tease about the visual approach to that film.

KAMINSKI: Well, yeah, I'm not going to hide. It's probably not my most favorable moviemaking, being on the virtual reality set and working with motion capture. It's really great for the director because he or she still directs actors. They still have to follow the physicality of the set, although it's a virtual set. But there's some elements of the set that the actors can crawl through, walk through, sit in, very minimal. It's fine for the director. For me, I established the lighting style in the post-production stage. Sometimes I participate. Sometimes I oversee the shots you know, depending on the particular situation.

Right now, I'm timing the movie, and the movie looks spectacular and 60% of the movie was created by visual artists, but they are following some kind of lighting that I established in 40% of the movie, which was live action, also shot on film. So they are following lighting that I've established in this movie, Ready Player One, and also in previous movies. They using imagery from other movies that I've done with Steven and they're reproducing the light that I would create. Some of the light from Minority Report. Some of the light from Artificial Intelligence. So they’re following the philosophy of my light. So essentially I would say it is my movie, my visuals, but many of the visuals were created artificially by very, very skillful animators.

I like movies like Bridge of Spies, Munich. The Post. I like movies that require as little visual effects as possible and I like live action, you know the location, being on the set. It's not always my favorite thing. Fortunately, it's not always Steven's favorite thing either so we usually break the time we spend on the movie set with being on location. We love being on location. That's where we go all over the world. I suspect often the money is the main reason, tax incentives, but really we go because we want to be on location, because if you make a movie on location, you focus on the movie, you separate yourself from that reality of life and you’re not on the movie stage, which is great.

So is Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara kicking up again soon? Do you know when that starts shooting or is that on hold for a minute?

KAMINSKI: I think so but I really don't know, you know, so many things. We're going to make Indiana Jones. Steven is the master of his own destiny and he makes the movie that he does. He might not even know what he's going to make next. Because this movie came out so fast you know? In May he read the script and we started making it two months later.