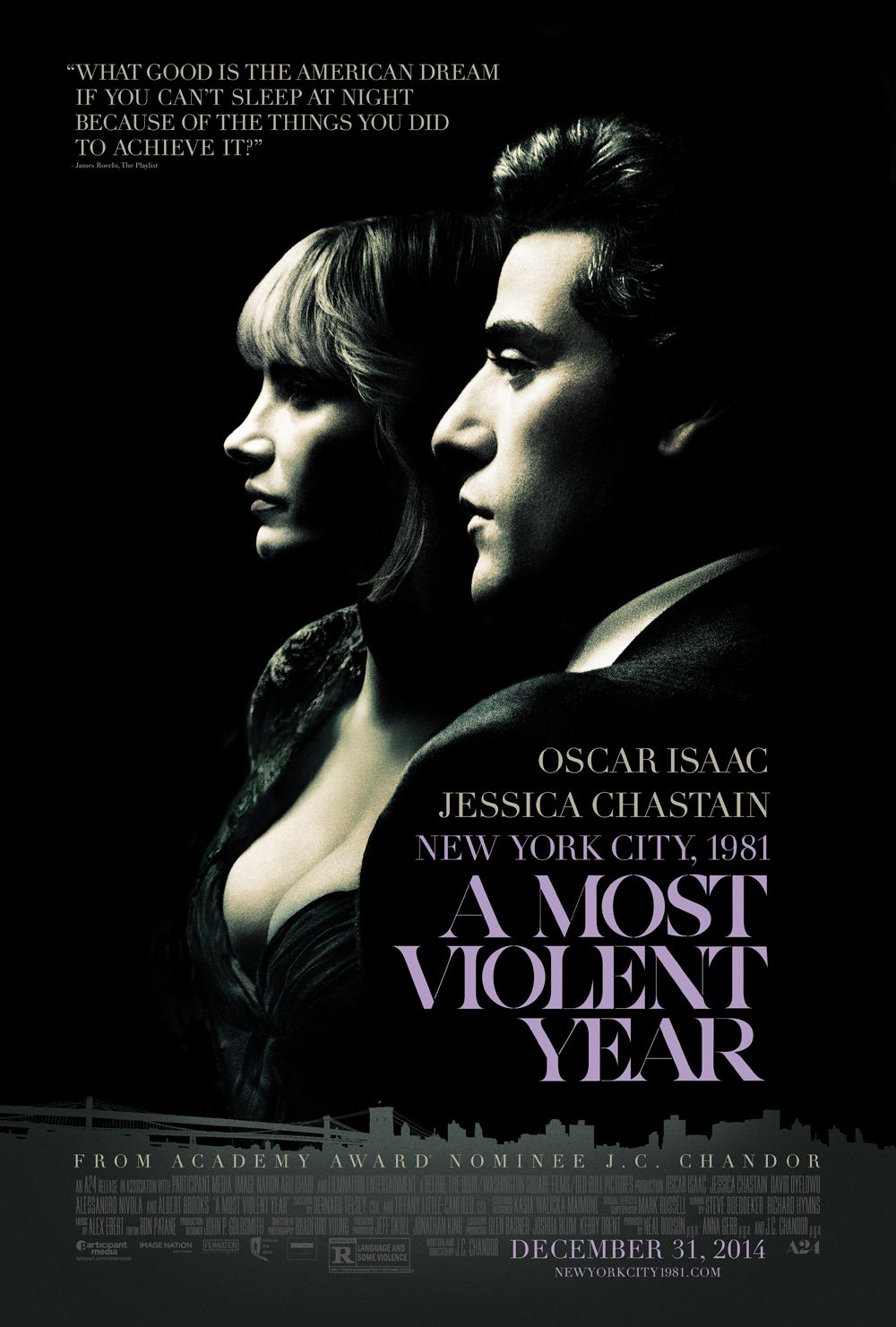

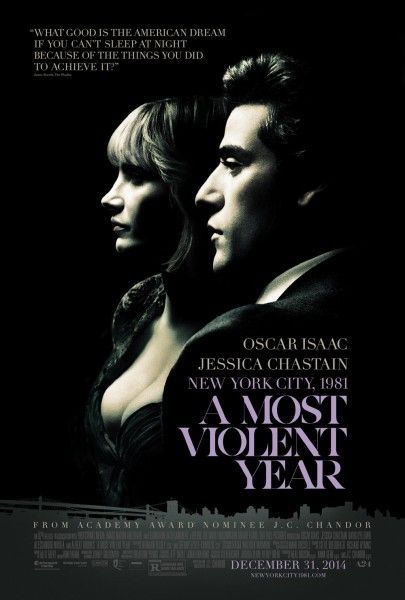

You want to know how an Academy Award nominee comes up with the concept for his next movie? You’ve got to check out what writer-director J.C. Chandor told me about his latest, A Most Violent Year. The film takes place in New York City in 1981 and stars Oscar Isaac as Abel Morales, the head of Standard Heating Oil. All Abel wants to do is run a successful, reputable business, but in such corrupt, violent times, that might not be possible.

With A Most Violent Year due for a December 31st limited release, I got the opportunity to sit down with Chandor to discuss how he went about putting this movie together. I only managed to squeeze two questions into our 10-minute interview, but it was well worth hearing the complete story of how he decided to make A Most Violent Year his All Is Lost follow-up. Hit the jump to read about that and Chandor’s next project, Deepwater Horizon.

Can you tell me about choosing to direct this one after All Is Lost? Is there anything that you experienced while making All Is Lost and maybe even Margin Call that made you think this was the right next step?

J.C. CHANDOR: Yeah, I mean, I’m writing these things, so it's a little different because I'm starting these things as a writer. Even though I'm writing them as a movie I'm always thinking this is just a scene in a movie, but I try not to think about the process of making the movie because you can not be serving the characters the way you need to be. My first two scripts I was able to write not even knowing if they were ever going to become a movie, which is a great freedom because you're following your own idea of what's best and not, ‘Oh my god, I've set so much of this movie at night. I'm going to have to be shooting nights for the rest of my life,’ you know? When you start to think that way it can affect your writing, which is not a good thing obviously. You want the writing to be servicing the character in the film, not your production demands or whatever.

But certainly coming off of All Is Lost, which I was writing this process while I was editing All Is Lost, which was a very lonely undertaking. Look, I mean that was a weird, weird process making that film. It's weird enough just watching it for two hours, but I was spending four years of my life - not really four, but two writing - but you're spending a year and a half, two years of your life literally with one person, one character, one face. It's an odd undertaking that I probably will never do again, but was fascinating and I learned so much and I'd never give it back, but I definitely wanted a big, multi-location, huge ensemble-y kind of jigsaw puzzle, absolutely. So I think I was reacting to that. But, you know, I'm building these things in my head and not really even realizing how they're being built.

There was one kind of tumbleweed rolling down the street is the metaphor I use for it [laughs], that was probably for five or six years just collecting ideas about a husband and wife team, analyzing their space within capitalism, what their goals were, what their ambitions [were], what happiness meant for them. I was kind of working on that and then I had this other concept about violence in movies that was kind of growing over the last two years. Since I made Margin Call I was just getting offered all these violent films to write and direct, which seemed sort of odd to me because I’m like, ‘I made Margin Call.’ But in analyzing it, it's like they're thinking, ‘He made this boring thing kind of tense and exciting, so add guns or masked murderers or whatever to that, he could probably do a pretty good job with that.’

So I was just getting all this material that was sort of like bumming me out kind of, and then this terrible violent act happened near me, which was the Sandy Hook elementary school shootings, which happened about two towns over and I have young kids in school. I drove my daughter to school after that and there was suddenly an armed guard at the door of her school and this idea of escalation started to - so like, horrible act of violence, terrible for everyone involved, their lives will never be the same, but the true damage from those kinds of things sometimes for society is the waves that go out from it. If you look at 9/11, so it's the reaction. You have the action, reaction, and then you've got another one and another one and next thing you know you've got World War III going on.

So this is literally happening in front of my face where I'm driving in every day and then I see these woods right across the parking lot from the front door and my pragmatic brain, I'm like, ‘So now you've got some sociopathic 17-year-old who gets to …’ It's almost like

you're asking them, right? He gets to hide in the bushes, shoot this poor guard that’s sitting there. Like, what does he know? And now we're right back where we were and someone could come marching into the school. And let's be honest, the chances of that happening, thank god, are slim to nil, but our reaction to this one act has now got 400 kindergartners who think that to somehow feel safe or whatever, they have to walk by an armed guard to get into their elementary school. So it's just this process of escalation.

So I start looking into crime statistics, just as I'm writing things, and I start wasting time on Google, the way you do [laughs], and I'm looking and I just was like ‘I wonder what the most violent year ever in New York City was,’ and randomly it comes out to be this amazingly transformative year for the entire city. New mayor, new president, huge case about violence called the Bernie Goetz trial, which was this guy who shot someone in “self-defense,” but once the trial was over everyone realized the kid looked at him wrong, so he called it "implied harm.” So this act of defense very obviously became an act of offense. So the city, in that year, made a choice that they were not going to become the Wild Wild West where everyone was walking around with a holster on their side. They were going to go a very different - they were going to take the streets back, basically, and that started all in 1981. The 70’s, just the violence every year worse and worse and worse and worse as the city property prices plummet, people's taxes plummet, the city has less money to pay for police force. I think the police force had been cut like 35% total by the time this year came around, so it was just out of control. That all seemed like pretty ripe material to set this character study that I had been working on about people that were kind of striving for success, but wanting to do it in a way that was just the way you or I do. Obviously I'm playing off the idea that these people are in a gangster-like culture, but that's mainly your perception from other movies you've watched, which of course is sort of the trick I'm playing on you [laughs].

How did you figure out where Abel would fit in that world? You could have put him anywhere on that spectrum in terms of him being a good guy who’s got to do bad things.

CHANDOR: Yeah, for me, I never had him doing any bad things. Some people, depending on their political beliefs or whatever, they sort of give him attributes that he actually doesn't possess. They’re like mildly cooking their books, which at that time is literally what everybody in the heating oil business was doing because it's a very cash rich business. You basically couldn’t be in business unless you were creatively kind of doing some things. And I'm not saying that's right, I’m just saying that's the reality. So he's trying to operate within the reality of what we're doing, which is just like you or I are trying to do journalism. You're a young journalist coming into the world right as journalism imploded on itself, right?

Pretty much.

CHANDOR: Yeah, so what are you trying to do? Do your freaking best to maintain your goals of wanting to be a journalist with your life while people are dying off. It's like the Night of the Living Dead here for institutions, journalist institutions, so that's a challenge. If you were to start the next JustJared or something, I would not hold it against you. Maybe I would, maybe I wouldn’t. These are the struggles so it’s like, I work in this film business trying to make movies. Life is complicated, right? It's not black and white and so they're just doing their best, but what we're seeing them at is obviously this month in their lives where it’s that month where they could be drawn into something very different. That point of weakness of all those things happening to them is sometimes when mistakes are made, as Abel says to Julien’s wife, that you can't recover from. So Julien's under all that pressure and instead of just sitting there and going to jail for 24 hours and then probably Albert would have gone and gotten him out of jail and he would have gone on happily with is life - maybe not happily, but would have gone on with is life - he decides to run on that bridge scene and panics and lets his ego get a part of it and the next thing you know he's run right into the grindstone of somebody else's political issues, which is David [Oyelowo’s] character is now gonna use him as a pawn, right? So that's a mistake he made.

One time somebody offers you $20,000 to write a hit piece on someone - I'm making this up, but whatever - you’re like, ‘Give it to me,’ right? But right in that moment when you need $2,000 to pay your rent and I'm offering you $2,000 for a good review, so it all comes about right at that moment and that's what I find sort of great to make a movie is in those moments when ordinary people, by their own doing, it's not like there's a meteor coming in here and gonna smash us and we had nothing to do with it, these people have all put themselves in these predicaments, but what they choose to do once they're in them is what I find kind of fascinating.

Before we wrap up, I wanted to ask you about Deepwater Horizon.

CHANDOR: There's things about that movie - I'm writing it right now. So, I’m working with David Barstow, the original writer of the New York Times piece that it's going to be based on, and he's gone back and we've had this whole team of research assistants that have gone through like every public trial. It's amazing working with them. It's so fun. If I wrote that, you would not believe it so we're literally just doing what happened. There's sort of no other option. I mean, it’s BP, if we lied and made stuff up, we would be sued so …

Who's perspective are you telling it from?

CHANDOR: Everyone's that was on the rig. It's just the rig though. So you're on the rig. So it's sort of a cross section of what happened that day, which is this unbelievable confluence of events, basically. Some BP execs land on the rig to like, give an award, but they're not really there to give an award. They're actually there to say "hurry up” because they were tremendously behind schedule and literally it blows up a couple hours later. And then everyone has to get off. I'm sort of structuring this film almost like this tragic sort of poem as to where human beings’ relationship with oil is right now, which is we need it, we love it, we want it, we're using a lot of it and we're running out of it, and that's just the facts. Everything in the movie will be what happened and Lionsgate is making a huge, exciting bet that there's an audience out there for big, dramatic blockbuster, summer-type blockbuster storytelling. And I don't think the movie's coming out in the summer, but it's a big ass movie but about real people, real things that happened on this planet right now and those are the kind of things I'm fascinated in so I feel humbled and honored to be given the chance in this day and age when most of the movies on that scale of storytelling are straight sort of entertainment - which this will be. You can't make it up it's so dramatic, but it's also really interesting just about where we are right now with our relationship to oil. We're building the set right now. I'm trying to hurry up and finish the script before they - it's never good if the set is finished before the script is.

Are you building a rig on a soundstage?

CHANDOR: We're building a rig in the parking lot and then gonna surround it in a huge tank of water. So we're building the rig almost life-size based on the original plans, which are public record, so we're literally building the rig in the Six Flags Great Adventure parking lot.

Around here?

CHANDOR: No in Louisiana for casting purposes. A lot of the extras and everything are from down there. That's where a lot of the workers were from so we're gonna be very hot next spring. That movie starts shooting in April.

For casting, last I heard was Mark Wahlberg.

CHANDOR: He's in the movie. He's very attached. It's a huge ensemble though so there's probably eight main characters and then 126 other people - but more than that, probably 150 people cast so it's gonna be a lot of casting.

I look forward to writing up every single casting announcement!

CHANDOR: [Laughs].