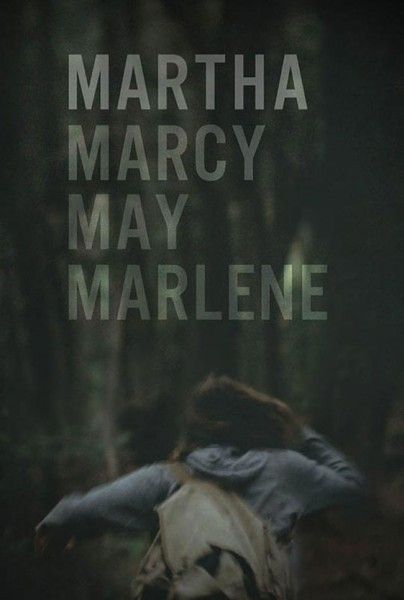

Martha Marcy May Marlene is a psychological thriller about a young woman (played by Elizabeth Olsen) who undergoes a crisis of identity after escaping a cult-like farming community where she suffered unspeakable abuses. As her past memories flash throughout her present, the audience gets to catch glimpses of manipulative community leader Patrick (John Hawkes), who is as chilling as he is charming.

At the film’s press day, the always complex and fascinating actor, John Hawkes, spoke to Collider for this exclusive interview about wanting to layer this character in a way that would keep him from becoming clichéd, approaching this more as a misguided community than a cult, not judging the character so that the audience never quite knows what to make of him, and quickly seeing how special and dedicated an actress Elizabeth Olsen is. He also said that he’s about to start work on Steven Spielberg’s movie about Lincoln and, although he cannot talk about it, the script is “really wonderful.” Check out what he had to say after the jump:

Question: How did this come about for you? Was it something that you sought out, or did they approach you about it?

JOHN HAWKES: They approached me. I went into reading the script with a little skepticism. I don’t even think I read it until it sat for a day or two because the word cult was thrown in, in describing the film, and I’m just not so interested in stories of cults. I’m not against it, or anything like that, but it just feels like something that’s been covered a great deal. But, the word cult was never in the script. It felt more like a community to me, however misguided, and that was a more interesting approach. It took away a lot of the preconceived notions and freed me up to take an approach that was perhaps less trodden then we’ve seen. It also made a great deal of sense for the character of Martha.

As an actor, I always approach things with a general beginning of, “What is the story?,” and then, “How can my character help tell that story, in the most interesting and vital way?” We need to be with Lizzie Olsen’s character Martha on this trip, and it offers her some credibility by having my character, Patrick, be a believable person. The instant that we, as an audience, see him and, in turn, she sees him, and he’s evil incarnate and the devil who’s a mustache-twirling Svengali type of charlatan, if that’s evident at the top, then we have a less interesting trip with her. Conversely, if we can see why she might have fallen in with this group, and the guy is a little more elusive and nuanced, it makes her character more credible and makes us more apt to stay with her on a pretty rough ride.

Don’t you feel that the lack of use of the word “cult” makes the story itself more identifiable for audiences?

HAWKES: I agree. I think we’ve all been misled, at moments in our lives, certainly in school situations, and things like that, with getting with the wrong group briefly, or falling in with someone who we learn the truth about and no longer want to really be with. Staying away from the cult thing, it is more relatable. Lizzie has mentioned that it’s less about a cult and more about a person, and specifically in this case, a young woman who has been traumatized and is dealing with the effects of that. In this case, she’s dealing with it alone, even though she’s with her sister and new husband. It’s also interesting that, as an audience, we know more than those two characters do. We have an inkling of what she’s been through, and we certainly know more than they do. By the end of the film, we know way more than they do or will ever begin to understand. They’ve only seen a shadow of what we’ve seen. That’s interesting, as an audience, to watch.

Since audiences never really learn what brought Patrick to form this community, did you figure out that backstory for yourself?

HAWKES: Yeah. In the time between when you first read a script and are offered the role and the time when you begin to shoot, I really love putting in the time and work on that and getting a solid backstory to a character and researching all that I can about what that person does for a vocation or their upbringing or where they’re from. In this case, it was a different way of working. It was more by subtraction. I knew what I didn’t want to do. I didn’t want to make the character the clichéd cult figure that we see a lot in stories. So, it was almost a bit of a leap of faith to be less prepared and more in-the-moment of what was happening.

When I over-prepare, I try to let it all go and forget all about it when the camera rolls, so I can just be present with the other actors and allow what’s going to happen to happen without too much preconception. In this case, I liked the idea that the character is a bit of cipher to the audience, and I thought that, if he was a bit of a mystery to me, that might be interesting. I think we’re all mysteries to ourselves.

It wasn’t being lazy, on my part, at all. I did think of a bit of a backstory for him, but it became almost forgotten by the character, himself. He was just there and present. I always pictured him just falling from space and landing there, and being this person that we don’t know much about. We know nothing about his past, and nothing about what his future holds. The only thing we can grasp hold of is what we’re seeing in the moment. The script was so rich, in that way, and so elusive and offered so many questions, it was unusual, in that way, and I wanted to respect that and stay with it.

Was it ever a challenge not to judge who this character was and what he was doing, and still understand why he was being so manipulative of these people?

HAWKES: I try not to ever really judge any character that I play, and certainly don’t think of it in black-and-white terms, like good and evil, or happy and side, or well-adjusted or not. I just wanted to make him a credible human being. The more conflicting layers there were, the better. Martha can’t quite figure him out. The other people in the community haven’t seen through him. I was fine with the non-judgmental approach that pulled from both extremes of tenderness and brutality, and good and evil. I wanted to invest lots of different qualities in him because it made sense for the story. I wanted to make him as elusive and slippery as the story itself.

Was it a conscious choice to make Patrick so charming, initially, instead of showing that evil side of him, or was that in the script?

HAWKES: It was partly written that way, and it was partly the choice that I may have made, along with the director, in how to play those scenes. As a creative person, you’re a storyteller, on some level, and when you tell a story, you never want to play the ending. If a character is going to turn out to be one thing, or if they’re written so strongly that there is this one distilled quality, it’s most interesting to me to try to cover it with as many layers as I possibly can, and let it just poke out through the cracks, once in awhile. That whole community seemed to operate best with this illusion of freedom that you could do what you want. And, it’s not even necessarily an illusion. People can leave that place, as Martha does, in the beginning. You may be followed, but you won’t be thrown into a windowless van and tossed over a cliff, or anything like that. You would then have to just live with a fiercer hell than death, in a way, by trying to make your way after having been damaged so deeply that you, yourself, can’t even begin to figure out what has happened to you or how you would begin to amend it.

One of the most interesting aspects of your character is his subtle manipulation with changes people’s names as he would meet them, essentially taking their identity without them even realizing it. How did that develop?

HAWKES: That’s something that we do, anyway. If you play in a band, you give each other nicknames. If you’re on a baseball team in high school, you give each other nicknames. The great thing is that there’s a side of that that’s affectionate and joyous, and is a gift he gives to someone that he cares so much about. He’s taking the time to think of something else that suits them, in addition to their given name.

I think (writer/director) Sean [Durkin] had the title of the piece before he began to write, so he might have always had that in his mind somewhere. I do know that I pressed for reinforcement of that, and Sean was kind enough to use it that way. When he meets Martha, he says, “You look like a Marcy May.” But, it wasn’t in the script, or it had been lost along the way, that when the young girl shows up, they say, “You know Sarah?,” and he says, “Sally, yeah.”

It seemed like a moment for humor, and it does get a little laugh, although not a cheap laugh. It’s all part of the piece, and any pieces of humor that we could find in the story were good. Sean certainly looked for them as well. That’s life. There’s always a mixture of things. The more they mix in a truthful way, the richer the story.

How was it to work with Elizabeth Olsen? Were there things that you did to make her and the younger girls on set feel comfortable for some of the intense scenes you had together?

HAWKES: Yeah, I hope so. The most intense scenes were with Lizzie. I was immediately impressed when I met her. She seemed like a delightful person. We all stayed in a motel along a highway, and most of us didn’t have cars, so the only place to eat was a café/ bar on the grounds. We’d meet there after shooting because there was no place else to go. I met her there when she arrived, and I didn’t know her family background or that she had famous sisters. I just thought, “This woman is so delightful,” and she seemed to delight all those around her, in a way that seemed really true and real.

When we began to shoot, I pretty quickly knew that I was around a special actress. I sensed an intelligence, a sense of humor, a dedication, and a way of approaching her work that seemed uniquely her own, and always seemed to the greater good of the story, which is so terrific. She was also tireless. She was working on her first movie, playing a supporting role, at the same time that she began to shoot ours, an hour away in the Catskills. She was driving back and forth on different days, probably getting very little sleep, but I never heard her complain. She was so game, and courageous, vulnerable and open in her work.

She and I had the most intense scenes, and I never want to physically hurt someone or emotionally abuse them, in a way that isn’t part of the story. That was the tacit agreement that we had when we worked together. But, with Sean’s help, we would just check in with each other, after each take of scenes that seemed emotionally or physically brutal, and just made sure that we were both okay. Sean shot those scenes in such a way that didn’t seem exploitative to either of us. I think we felt taken care of and allowed to do our work, in a way that is rare.

Do you know what you’re going to be doing next?

HAWKES: I’ve finished a lot of little independent films that are pretty cool. They’re all in various stages of post-production. And, I’m about to start a very not independent film, but a really wonderful script. It’s the Steven Spielberg movie about Lincoln, that I’m apparently not supposed to talk about at all.