From his role as the forerunner of shock-driven cinema on the underground movie circuit to his unlikely transformation into the critically adored “Pope of Trash,” John Waters’ career has successfully shifted from a place of public provocation and mass revulsion into a space of auteurist praise and intellectual intrigue by critics and audiences alike. This week, as Pink Flamingos becomes the fourth of the director’s films to enter the Criterion Collection, it is essential to acknowledge the bold and subversively beautiful balance of unprecedented queer celebration and countercultural shock value held within Waters’s breakout hit fifty years after its original release. From the glorious scene of Divine parading around Baltimore to the tune of “The Girl Can’t Help It” to the infamous final sequence, Pink Flamingos helped define the midnight movie through its dismantling of good taste as well as its promotion of a burgeoning queer cinema centered on self-acceptance and public expression. By solidifying Waters’s trash-infused camp sensibility through the story of a community competing to uncover “the filthiest person alive,” Pink Flamingos remains a shocking Midnight masterpiece and delightfully subversive expression of queer freedom.

Combining the cult showmanship of midcentury auteurs like William Castle and Roger Corman with the countercultural aesthetics of New York underground artists like Andy Warhol and Jack Smith, the career of John Waters leading up to Pink Flamingos saw the director subvert traditional modes of cinematic viewership as a form of deliberate rebellion against a Vietnam-era conservative establishment. By utilizing the notoriety of his works as word-of-mouth advertising, John Waters transcended his low-budget trappings to gain a cult audience from the outset of his career. Starting from his early short films like Eat Your Make Up, which saw Divine impersonate Jackie Kennedy to hilariously brutal ends, and Mondo Trasho, a mostly silent proto-Pink Flamingos, Waters gleefully upended notions of public decency to help create an alternative cinema outside of the structures of personal propriety and storytelling decorum. Although the infamous lobster sequence and “rosary job” at the center of his first feature Multiple Maniacs ignited his filmmaking career through controversy-driven subversive marketing, the seemingly endless menagerie of shock humor in Pink Flamingos illuminates how the film to tower above the rest of his career as Waters’s definitive countercultural statement.

From the opening trailer park set sequence introducing Divine as a chief competitor for the position of “filthiest person alive” to the infamous dog poop sequence that concludes the film, Pink Flamingos maintains an unprecedented pace of shocking moments without ever dipping into humorlessness or empty provocation. By situating the film on a bad taste battle between Divine’s antihero Babs Johnson and The Marbles, a kidnapping couple played by Waters’s stalwarts David Lochary and Mink Stole, Waters engages an increasingly grotesque crescendo of transgressive behavior to critique the perceptions of the Vietnam-era counterculture held by the Nixonian public. Featuring darkly humorous sequences of surprise flashing, unspeakably bad birthday gifts, and even faux murders, Pink Flamingos channels societal fears into a cathartic collage of rebellion that uncovers the most disturbing corners of midcentury America for satirical involvement. Even as the infamous climactic scene depicts Divine eating dog poop to prove — in a meta-moment narrated by Waters himself — that she is both the filthiest person and the filthiest actress on earth, Pink Flamingos never loses sight of its import as a sociocultural statement and a cult artifact.

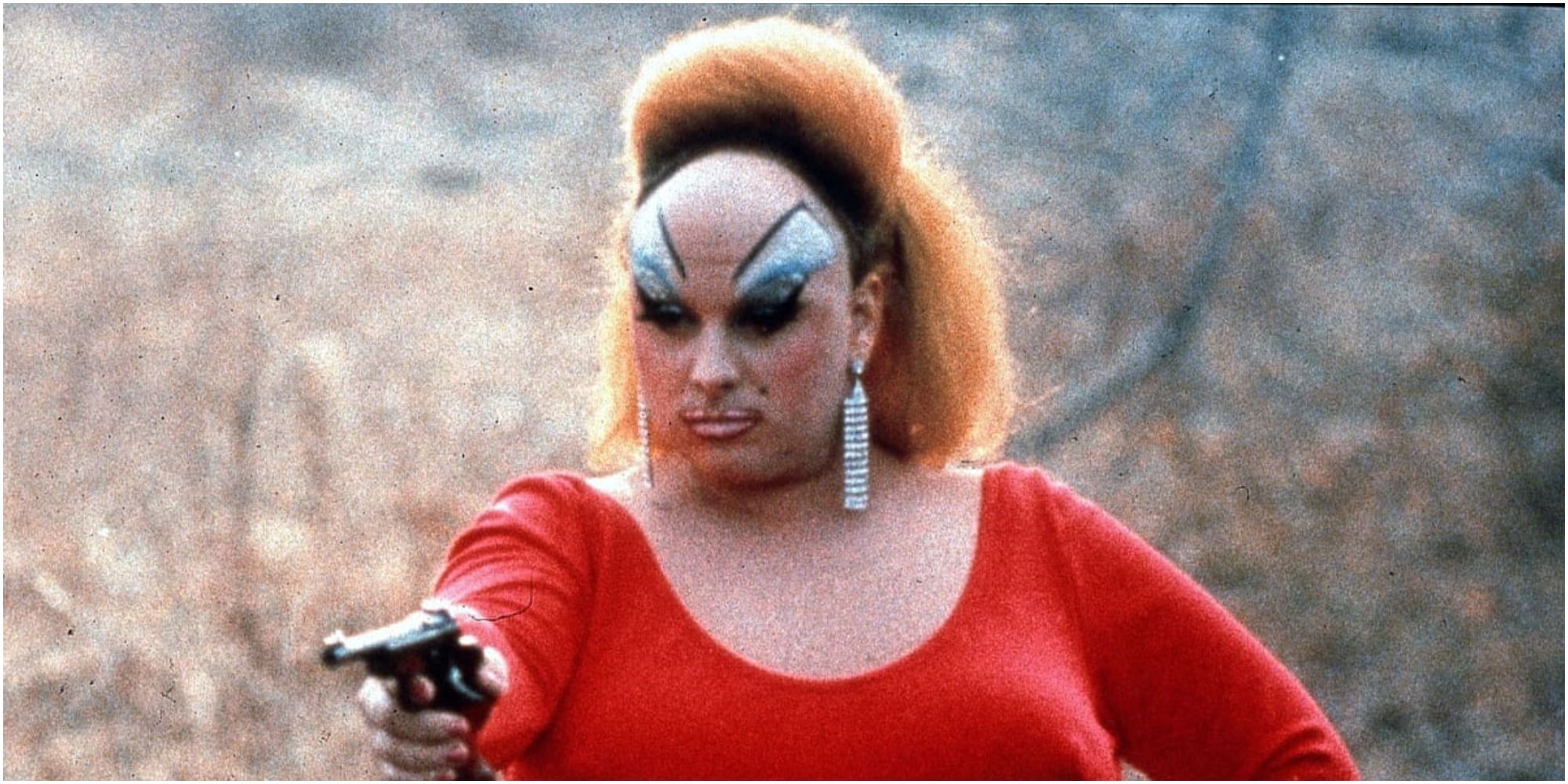

Yet in the midst of the onslaught of filth that pervades Pink Flamingos, John Waters sneaks a meaningful story of queer self-declaration centered on Divine’s pursuit of subversive greatness. By employing trash aesthetics as a Trojan horse for a message of queer belonging, Waters manages to reframe the midnight movie as a triumph in the modern canon of LGBTQ+ cinema. Although much of the contemporary praise for Pink Flamingos as a positive work towards queer liberation focuses on the film’s role in communal representation, it is also essential to acknowledge how Waters’s elevation of Divine points towards a more personal engagement with the onscreen prowess and unconventional beauty of his leading lady. In particular, the extended naturalistic sequence of Waters following Babs Johnson across the streets of Downtown Baltimore frames Divine within the various looks of shock, awe, and delight from the crowds of people along the sidewalk. Underscored by the percussive beats of Little Richard singing “The Girl Can’t Help It,” this early docu-style sequence in the film functions as an act of celebrating Divine’s individuality as a pioneering drag queen and foundational queer icon. Furthermore, the gun-toting, red dress-wearing Divine that brings The Marbles to filthy justice in the film’s final act effectively subverts the heteronormative anti-heroics of contemporaneous films like Dirty Harry, emphasizing Divine’s revolutionary fluid star power.

Beyond the oppositional movie stardom that Divine inhabits throughout the film, Pink Flamingos provides a sweet glimpse into the importance of found family in the queer community. By highlighting a heightened working-class domesticity within the camp aesthetics of Babs Johnson’s carnivalesque trailer, Waters creates an alternative vision of family centered on an exhilarating engagement with anarchy. From Babs’s mother Edie’s (Edith Massey) obsession with eggs to the voyeuristic inclinations of her son Crackers (Danny Mills) and best friend Cookie (Mary Vivian Pearce), Pink Flamingos highlights the character quirks and narrative gimmicks of the onscreen figures through the film’s examination of alternative taste. Beyond the fictional family with which Babs surrounds herself, Waters collaboration with his closest friends transforms Pink Flamingos into a meta-portrait of his own found family and their alternative artistic interests by providing the performers with a punk playground to dismantle prevailing taste politics.

Although the rise from the smut-filled screens of underground cinemas to the international canon of the Criterion Collection seems like an unlikely trajectory for a trash-filled spectacle, Waters’s emphasis on empathetic engagement with alternative communities and revolutionary elevation of alternative artistry sets Pink Flamingos apart as an essential work of queer cinema. From the triumphant parading of Divine across Baltimore to the atrocious acts of abjection that fill out the film’s most infamous moments, Pink Flamingos remains an endlessly enthralling cacophony of controversy. While normative international audiences scoffed and even banned the film on its initial release, the sociocultural importance of Waters’s message of self-acceptance and queer expression has empowered Pink Flamingos to transcend the trappings of its trash aesthetics to become a necessary artifact of the New Hollywood. Encapsulating the individualism of its director and stars through an engrossing investigation of transgressive taste, Pink Flamingos continues to shock and delight audiences in meaningful manners fifty years after its debut.