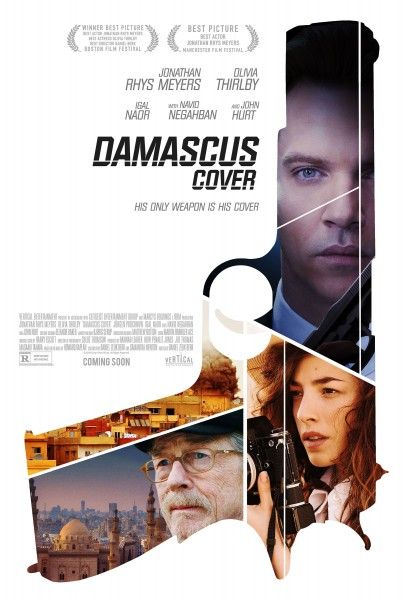

From director Daniel Zelik Berk, the spy thriller Damascus Cover follows Israeli spy Ari Ben-Sion (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), a man who is haunted by the death of his son and who now finds himself on a mission to smuggle a chemical weapons scientist out of Syria. Ari soon finds himself in the company of a young American photographer (Olivia Thirlby) and as the mission starts to go wrong, he discovers that he is merely a pawn in a much bigger plan.

To discuss the film while he was in Los Angeles, Collider got the opportunity to sit down with actor/producer Jonathan Rhys Meyers to talk about the very complicated character at the center of this story, living in a world of lies, putting all of himself into the role, seeing himself more as an artist than as an entertainer, actually getting to learn from real people who understand and live in a world like the one in the film, and the decision to set the story in 1989. He also talked about his working relationship with Michael Hirst, on The Tudors and Vikings, why he wanted to start producing the projects that he works on, how being a producer has changed him as an actor, and how he goes about deciding what type of project he wants to be a part of.

Collider: I love these kinds of movies because when you just can’t figure out what’s going to happen next, it’s always really fun. We see so many movies where it becomes so easy to see where something is going. And this still surprised me.

JONATHAN RHYS MEYERS: You are so very, very kind. We worked very, very hard at that – myself and (writer/director) Dan [Zelik Berk], and the whole team.

That’s not an easy thing to do.

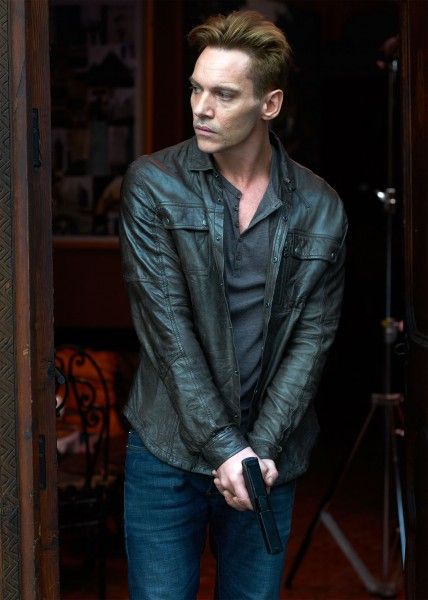

MEYERS: No, it’s a very, very complicated story because he’s an intelligence officer and he’s a spy, but he’s also somebody who is responsible, indirectly, for the murder of his own son, leaving a loaded gun in the house and his son shooting himself. There’s no way for his spirit to regain after that, so what he’s carrying is the soul of a dead child within him. Then, he goes out on a mission immediately afterwards, fails in his mission, comes back already a broken man, has to go to HR for mental health training, and they see in him this vulnerability. And then, they send him straight back into a situation where his sense of vulnerability may be successful for the mission or it may get him killed, but in Ari Ben-Sion’s heart, he’s looking for that bullet. He feels he deserves it.

How did this come about, especially with you being producer and an actor on it?

MEYERS: Well, I met Daniel a few years ago. We immediately clicked and we immediately understood what we wanted to portray, which was the really, really dark, uncomfortable, soulless side of what these people do. They give their lives in service to their country. Their successes are never known, and their failures cause international travesty. When you give your life to that type of service, you will never be thanked for it. These are people who sacrifice any element of relationship and any element of happiness, for what they believe is the long-term greater good. However, it doesn’t always seem like the greater good, at the time. Sometimes they feel like they’re doing more damage than they’re doing good.

What’s it like to play a character who has to live in a world of lies, to the point that he probably loses sight of who he actually is.

MEYERS: His name is Ari Ben-Sion, but he’s pretending to be Hans Hoffmann, and Hans Hoffmann isn’t the first person that he’s had to pretend to be, in his life. In many ways, it’s like a cracked actor who’s constantly moving from one performance and one reality into the next reality. However, actors do the job and go home. Intelligence agents go home in body bags and they’re buried in unmarked graves. Only their close friends, the ones that they’ve protected, will have little memories of them. It’s a heartbreaking sadness of the reality of the world that we live in today. There should never be a necessity for an Ari Ben-Sion, but there is a necessity.

As a father, does it personally affect you to take on a role like this, or do you try to keep that separate?

MEYERS: No, I take it all with me. I saw Ari’s son the same way as I see my own son. In the scenes where Ari closes his eyes, I envision my own son. What would I feel? How would I do it? How would I survive? Ari is stronger than anybody you could possibly imagine because what a lot of men would do in that situation is kill themselves. Ari decides to use his death to try to save this girl and her family and get them out, so they don’t suffer the same fate. [At the end of the movie], Ari is broken. What is up to the audience to decide is whether the next thing that happens is a gunshot, and there is no Ari, you know? That is possibly the reality of what happened. Then, the character of the late, great, wonderful John Hurt says the most beautiful thing in the movie when he’s on the phone and he’s looking at the little kids in the playground. He says, “Why are we still doing this? What have we been doing with our entire lives?” That’s the reality of this film. This is not the shoot them up, “I’m so suave, look how sexy I am. I’ve got a suit and a license to kill.” It’s not that. It’s the reality of what happens to these people.

I actually really like the fact that it is much more old-school, in that sense, and he’s not relying on a bunch of technology to help him out. If he needs to get out of a situation, he has to get himself out of a situation without any fancy gadgets.

MEYERS: Yeah. He’s not the world’s most intelligent man. He’s not the world’s greatest fighter. Not everything happens, immediately, the way he wants it. In our film, we do not use the tricks that films with $150 million budgets use. When they have a script dip, they just decide to throw a car through a skyscraper, but that’s not story. That’s like offering somebody sushi, and then giving them a cheese danish, half-way through. It fills up the hole of the story. We stay within the story, even if that story is uncomfortable to watch at times. Films are very, very many different things. They can be mindless entertainment, or they can be really heartbreaking mirrors into our own failures. You see it in the news, where 55 insurgents were killed in Damascus, but those weren’t insurgents. Those were 55 grandmothers, fathers, uncles, butchers, bakers, carpenters, and their children. “Insurgent” is a very good way of creating apathy for a situation which really requires empathy.

Sometimes I just like to feel challenged and really be left with something, after seeing a film, and this film does that.

MEYERS: I’ve never thought of myself as an actor in film as an entertainer. If I wanted to be an actor as an entertainer, I would have chosen other films. I’d have done an American Pie, I would have done this and done that, I would have made tons of money, and I would be driving a Lamborghini and sitting in the Chateau Marmont saying, “Aren’t I fabulous? Aren’t I fantastic?” I would have a Twitter feed of myself with my top off. That’s not what I want to do. I’m an artist, before anything else, and my life reflects that I am an artist, through my work. Whatever struggle I have within the outside of my life, regardless of what that is, I bring it into my work. I see film as a window into other people’s souls that we will never get to see. Nobody knows anybody. Not really. You would have to spend 24 hours on somebody’s shoulder to even get an idea of who they are. If you spent 24 hours on anybody’s shoulder, you’d find out that we’re all fallible. Ari Ben-Sion is the ultimate human being, with all the good and all the bad. He’s a human, first and foremost.

It’s not every day that, for work and research purposes, you get to spend time with someone who is in this kind of profession. What’s it like to actually get to speak to an operative and learn about what they can share?

MEYERS: They’re very quiet. That’s the one thing that I have noticed about the people that I spoke to and the people who were involved in that type of world. They don’t talk about what they have done. They don’t talk about their situations very much. I also spoke to a friend of mine, here in Los Angeles, who’s a war photographer and who actually worked in Lebanon. He was in Somalia in 1992, when they dropped the bomb on the school instead of the weapons factory, and that wonderful American journalist, Dan Eldon, was beaten to death. Well, he knew Dan.

I have great respect for war photographers and correspondents.

MEYERS: He said, “I was in Bosnia and Herzegovina. I was in Srebrenica. I came back and I met a friend of mine for a drink in the French House,” which is a very, very famous pub in Soho in London. His friends said, “Oh, my god, you’ve just come back from Bosnia and Herzegovina. How was it?” He said, “Fine,” because there’s no other answer to give. It would take 10 years and 1,000 voices to be able to explain exactly what he saw and what happened, with the brutality, and the lack of respect for people’s lives. It’s a dangerous job, and anybody who does this job should be given an incredible amount of respect. I find it very, very difficult that people don’t give that amount of respect to the soldiers who come home from wars. They’re ignored, even though they give so much. Actually, they give everything. You can’t not see death once you’ve seen it.

There is a wonderful photographer, called Don McCullin, and he’s got a dark room in his house. He’s probably the world’s most famous war photographer. He took all of those very, very famous photographs during the Vietnam War and he stayed with a unit for a long time. He said the hardest photograph he ever took was in an orphanage in Rwanda, after the massacre in Rwanda. There was an albino boy who made him very uncomfortable because he was right next to him. He had a sugar lollipop in his pocket, and he gave the sugar lollipop to the albino boy and continued doing what he was doing. When he turned around, in the corner was this albino boy just slightly licking the lollipop because he’d never been given anything in his entire life. Now, this boy had one short sleeve and one long sleeve. That means he’d had one hand cut off and one arm cut off, so he’d been caught twice and he had no hands. That is a very, very strong image and Don McCullin said, “That image will never get out of my head. Sometimes I go into that dark room and that boy still speaks to me.”

That is where Ari Ben-Sion is. That’s what he has been through. That’s the trauma that these people go through. There was no way for Ari Ben-Sion to be able to walk into that situation, being Mr. Suave or Mr. Fantastic. It would have been so far beyond authentic that he would have immediately been found out. He carries it the whole way and Dan, my director, stayed with it, regardless of whether it was painful, whether it hurt, or whether it made the audience wince. This is a real story. Howard Kaplan had traveled all over the world and met tons of these people. His book is set in the 1970s, but we portrayed it in 1989. I did a film a few years ago with Roland Emmerich, called Stonewall, and one of the problems with doing films in the 1970s is that you have to go so cartoonish and over-the-top with the look because we have borrowed so heavily from that fashion time that it’s very, very difficult to distinguish that it’s a period film. But in 1989, everyone looked like shit. The music was great, but the clothes were dreadful. It allowed us to move it to what was a very dour, almost uncomfortable time, and a very, very dangerous time. We were very, very proud of how we stuck to our guns within the story.

I was also such a fan of your work on The Tudors, and I’m a huge fan of Vikings.

MEYERS: I haven’t seen anything of myself in Vikings.

It’s such a smart and well-done show, and I love how much attention Michael Hirst seems to pay to every detail. What’s it like to work with and have a collaborative relationship with him?

MEYERS: Michael is an intellectual. Actually, Michael’s thesis is not on history. Michael’s thesis was on Henry James, and I’ve just done The Aspern Papers, which I also star in and produce. Michael Hirst’s real area is the novels of Henry James. History can be an important lesson. When we made The Tudors, we were able to make a period TV show successful, for the first time. There would be no Game of Thrones, there would be no Vikings and there would be no Crown, unless we had done The Tudors first. It was the first time that the industry saw that we could put people with swords and horses and castles and gowns, and it would be successful. It was funny, we were on the third season of The Tudors when they greenlit Game of Thrones. The only reason that it was greenlit was because we did The Tudors first, and we’re very proud of that.

The characters in Vikings are all so fascinating, interesting and complicated.

MEYERS: Because they’re real. They’re complicated and they’re realistic. Ragnar Lothbrok existed. Lagertha existed. Ivar the Boneless is actually the greatest Viking warrior of all time, even though he couldn’t walk. He had to be carried into battle on a shield. That’s the reality. Now, he doesn’t look like Alex Høgh Andersen. Ivar the Boneless was a tragedy of a man to look at, but he had a viciousness in him that was unparalleled. He’s the only Viking ever to attack Rome and sack it. The character that I play, Heahmund, actually did exist, as well. He was one of the first warrior bishops. He is a precursor to what became the Knights Templar. But then, he’s not New Testament. He’s Old Testament, which is very different.

You seem to be producing a lot more of the projects that you do now. Was that something you always wanted to do, or was there something that created that shift of wanting to be more involved?

MEYERS: You do want to be a little bit more involved. As an actor, if you get the opportunity to be more involved, you do it. As an actor, to a certain extent, it’s out of your hands. You can’t taste the soup when you’re in the soup. You have to be outside of the soup, and then you have to trust the cook. You have to trust the director. But when you’re an actor and you also have a production duty, then you can help speed things up while you’re on the set. That is the greatest gift for an actor who’s a producer on something. They can cut through rope and lines, very, very quickly. Film is always interchangeable. You can go to the set with a Plan A, but you have to also have a Plan B, C and D because you don’t know what’s gonna happen and what’s gonna change, at any given time. You’re talking about something that’s art. Every single situation is different, so you have to be able to adapt. Picasso wasn’t the greatest painter, every day. Bob Dylan wasn’t the greatest songwriter, every day. It was the days that they were great singers, songwriters, painters, actors or directors that people will point out, but it’s a struggle. Art is a constant fight for elevation. That’s why it’s art.

Sometimes it’s very, very hard for people to recognize what good art is. If everybody recognized what great art was, then our great-great-grandparents would have all bought Van Goghs when they were five guilders instead of $500 million, or we would have been able to recognize Vivian Maier, who’s probably one of the greatest female photographers of the 20th century. Nobody even knew that she was taking the most extraordinary photographs of New York life, until much, much later on. It’s very, very difficult, in the present time, to be able to recognize what is truly great. It’s in retrospect. Even the plays of William Shakespeare weren’t appreciated in the time of William Shakespeare. They only became popular in the middle of the 19th century. The first-ever William Shakespeare play was never even printed in English. It was printed in German.

When you did start producing projects and became more hands-on, did it change how you were acting and working on, since you were thinking about everything more?

MEYERS: Yeah, it did. The first time I was a producer on something was the NBC TV series Dracula. I over-thought the whole process. I was looking at the monitor, after every scene. I remember having this conversation with the late, great Philip Seymour Hoffman, who I became friends with after Mission: Impossible III. He said he’d gone through the same experience with Charlie Wilson’s War, where he started obsessing about the monitor and whether everything was right. That’s not the correct way to go about it. My job is to go in there and to perform, and to stay within the performance. I had this conversation with Bruce Beresford, when we did Roots. He said, “You don’t look at the monitor.” And I said, “No, I don’t look at the monitor. I did that a lot during Dracula, and I thought it was detrimental.” He said, “You’re right, it is detrimental. I did a film (Crimes of the Heart) with Sissy Spacek, and she was brilliant in every scene except one. I walked up to her, after the scene, and I said, “Sissy, what’s happening? You weren’t very good in that scene.” And she said, “I looked at the monitor.” He said, “Don’t ever look at the monitor again. That’s not your job. It’s my job to take care of you. Your job is to stay within the role and perform it to the absolute extent of your authenticity. If you can do that, then people will appreciate it.”

What made you have the realization that you shouldn’t be looking at the monitor?

MEYERS: Because I was driving everybody bloody insane by looking at the monitor and taking up too much time on the film set. It was like, “You’re still looking at the monitor? We’ve got to get going.” Then, I realized that what I was doing was playing into the most detrimental side of my own ego. In Othello, the character of Iago doesn’t actually exist. I didn’t find this out until I worked with Cicely Berry, who actually teaches actors how to act Shakespearean dialogue at Stratford-upon-Avon. I had a conversation with her where she said, “Re-read Othello and look at the character of Iago.” I did, and then I realized that he doesn’t exist. Iago is Othello’s ego. He’s in his head. He has created a whole other person through the detriment of his ego. That’s why he called him Iago. It’s the closest he could get to actually saying ego. That understanding only comes when you really, really look deep into whatever you’re doing, as an artist.

How are you with watching your own projects, after they’re completed?

MEYERS: I don’t go out and rent my own movies, but I certainly see them at a screening.

A lot of actors talk about how they don’t like to watch themselves and that they won’t even watch their own work at the premiere.

MEYERS: That’s another side of the ego. They might not like sitting through their movie at the premiere, but I can bloody well guarantee you that they have it on DVD, and that they sat in a dark room and watched it, three or four times. Don’t believe that. Sometimes it can be uncomfortable because you’re watching a characters and you’re not watching yourself. You’re watching an element of yourself. Remember, the camera never lies. It has no ability to lie. It will show you what’s there. Sometimes it can be manipulated and it can show you a fantasy of what’s there, but it’s like numbers and mathematics. That’s why when a stock market crashes, it’s because they’ve lost control of the math. When you lose control of the math, it reveals itself because it’ll always tell the truth. One and one will always be two. You can never make one and one six. It’s the same with being an artist. It was very, very much part of our process in Damascus Cover. We were not trying to bamboozle people by blowing things up. We could very easily have brought in 40 machine guns and had five car chases, but they would have made no sense. What they would have done is distract the audience from what was really going on. We think of wars as fought between nations, but really actually they’re fought between individual human beings. The stories are so personal, and this is a story about what happens, personally, between a few people caught up in a much bigger picture.

After what you learned from doing Dracula, would you do another TV series?

MEYERS: Yes, but I would be careful about which one I chose.

Because you strike me as someone who does not want to do things that you’re not passionate about, what is it that gets you excited about a project or makes you say, “This just isn’t for me”?

MEYERS: I don’t know. There isn’t one answer for that. Sometimes you just have to work. Sometimes you want to challenge yourself. Sometimes you feel that you’re really born to play a role, or there’s a particular director that you want to work with. You look at actors who go to the Academy Awards and get Oscar nominations. Do they get them, or does the director give them the platform where the audience can see them? That’s what it is. If a tree falls in a wood and nobody hears it, did it really fall? As a performer, you need platforms. It’s actually surprising that any film works because you’ve got 200 people with 200 completely different jobs coming together to make one thing. Have you heard about too many cooks spoiling the soup? Making films is one of the most collaborative experiences that you can possibly have. Sometimes wonderful directors get waylaid by producers who are unsupportive, or writers who aren’t concentrating properly, or whatever. Sometimes people just don’t understand it, and sometimes people do. And sometimes people understand it much later.

I’ve seen a couple of movies that, when they first came out, everyone was like, “Oh, my god, it’s so brilliant! It’s so fantastic!” And then, you watch it, three years later, and you’re like, “My god, it’s really bad!” Then, you see some films that people didn’t really appreciate at the time, but three or four years later, you’re like, “Oh, my god, this is fucking genius!” Sometimes it’s the period of time when a film comes out. Did you know that The Hurt Locker was released two years before and disappeared? It lasted five days in the cinema, and then they re-released it two years later because the timing was better. That happens. Did you know that the movie Slumdog Millionaire was going straight to video before somebody in the video room who was actually copying it for the DVD went to the studio and said, “You should really release this in the cinema”? Suddenly, everybody was at the Oscars going, “Oh, my god, aren’t we great?” Sometimes you need a person with the eye to be able to see what’s really there. That’s what makes it fun. Some films are better than others, and some films get appreciated at different times.

Damascus Cover is now playing in select theaters, and is nationwide and on-demand on July 27th.