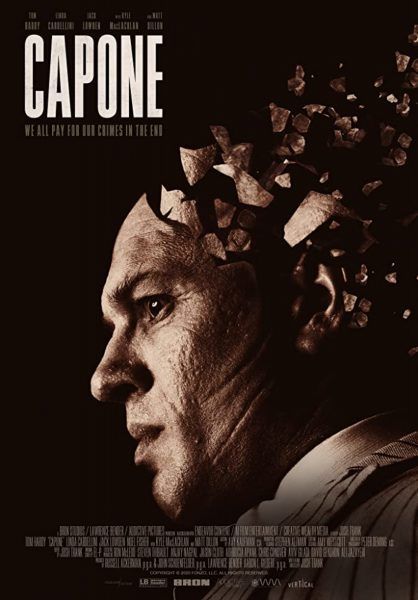

From writer/director Josh Trank, the indie drama Capone is a look at the most infamous and feared gangster of legend, at a time and age in his life when he was suffering from rapidly advancing dementia caused by untreated syphilis. After serving 11 years for tax evasion, Al Capone (Tom Hardy) returns to his life with his wife (Linda Cardellini), as his memories drift between his violent and brutal past and his present, at the age of 47.

During this 1-on-1 phone interview with Collider, filmmaker Josh Trank got candid, talking about how happy he is that people are finally able to see the film, as it’s been on a bit of a journey in getting to the screen, how he ended up exploring Capone’s life in this way, working out things that he was feeling and experiencing while writing this film, how shocking it was to see his past few years laid out in the recent Polygon article about him, the way the film was shaped as it evolved, why Barton Fink has been such a cinematic inspiration for him, the TV project about the formation of the CIA that he’s working on with Tom Hardy, and how he views the collaborative relationship that he has with the actor.

Collider: This film has had a bit of a long journey, on its way to finally being seen. Tom Hardy signed on in 2016, then he went and shot Venom and you didn’t shoot until 2018, and now it’s 2020. Is it frustrating when things take so long, whether it’s your star shooting a big studio movie or release dates getting shifted around, or do you just get to a point where you’re just happy that’s it finally coming out?

JOSH TRANK: I’ve gotta say, nobody has asked me that. This is the first time I’ve done interviews in years, really. I’ve done a lot of them, over the last many years, but just in terms of talking about something like this, it’s been a long time. Nobody has asked me that. It’s an interesting question, and my answer is that I’m really happy that people are able to finally see it right now. A lot of it has to do with what you were just saying about the fact that what most of us really have right now, keeping us going, is just things to watch. Although there’s a part of it that’s a bummer because you mix a movie on a big beautiful mix stage and you do the color correction, and you want people to see it in a theater. I’m just really happy that I can give something new to people to watch, as they’re watching everything right now. And maybe there’s some aspect of this movie that ironically and tragically is maybe a little more relatable than it would have been otherwise because it is about a person who’s isolated in their house. I don’t know if that’s something that could make someone out there feel a little less crazy and lonely.

But as far as the delays and the things that come with that, it’s just the nature of this business that we all get used to things being delayed and it becomes embedded in our expectation of things, for me there was a very different level of anxiety behind the meaning of this movie, coming off of Fantastic Four and that whole situation. The best way I can describe it is, the thing that you love doing the most in the world, imagine everybody starts writing articles saying that you suck at it. All you wanna do is just get back out there and show people that you don’t suck at it and that you love it. I’ve been jonesing for the moment to be able to make the movie, and then we made it and it was beautiful.

Everything that went wrong on Fantastic Four, is how everything went right on this film. There was zero drama, whatsoever. Everybody loved each other, everybody had fun, everybody had a great time, everybody knew each other’s names. It was a blast. It was the best experience, in my life. So, editing the movie, I’ve been alone, editing the movie, and that became its own process of discovery and experimentation. And I got to work with El-P, who’s one of my heroes. There were a lot of stages of this process, to finally get to this point. It took as long as it needed to take, in order for it to end up the right way. I couldn’t be any more proud of anything I’ve ever been a part of, in my life. I love this movie, dearly. It also, simultaneously, it gave me enough time, just as a human being, to be in the right place to feel at home again, in a lot of ways, or at home, for the first time. I’m not sure which.

This is not the kind of story that you would expect to see, when you’re watching a story about Al Capone. What made you want to explore his life, in this way? What was it about this part of his life that interested you?

TRANK: It’s a question that’s come up because of the name itself – Capone. The movie that I wrote and the movie that we shot, and that had been something that we were all working on together for a little over four years, was called Fonzo. The reason being was that I really loved that title, but it also relates, phonetically, to how we hear his name said by some of the characters in the movie, and it’s a movie about one’s relationship with their identity while their mind is in a deteriorating state. The most important thing about the movie, for me, before it was called Capone, is that it doesn’t really matter that it’s about Al Capone. It’s about somebody who, at one point, was Al Capone and who’s dealing with all of these swirly memories from his past, seeping their way into his present life. So, I had envisioned a movie that would come out, called Fonzo, that wouldn’t have the baggage of expectations that come with a biopic because what we set out to make was a weird, uncomfortable art house film with Tom Hardy.

Once we sold the movie to Vertical, it was amazing because they were very passionate about my cut of the movie. Obviously, that’s everything as a filmmaker, that I’ve ever wanted to hear, but the one compromise that was pretty much a non-negotiable was that they wanted to change the title to Capone. I had to sit on that for a few days because, to me, I felt that it drastically altered my own relationship with the identity of this movie because I just didn’t want it to have that baggage. And then, I watched the movie pretending it was called Capone, and I was like, “Okay, I can live with that. That’s fine.” It’s hard for me to tell whether or not that was the right move, for the title to be changed to Capone for more commercial purposes, so that when people see the name, they recognize it, but it is definitely brought up a lot of questions, specifically about Al Capone. It’s been less about what goes on in the movie, as opposed to what’s up with Al Capone. My desire to make a film about Al Capone didn’t come out of a bucket list, where I’d always had this angle on Al Capone, or I had a good idea that just popped in my head, that I was hanging on to.

It came from my own experience of being alone in my backyard, a few months after Fantastic Four came out. There was no incoming work. There was nothing really going on in my life. I was just me, facing myself, every day, and not liking what I was seeing in the mirror. I was disappointed in myself. Every day that was passing, I was feeling farther and farther away from my own personal heyday, so to speak of. It was a short amount of time, from 2011 through mid-2015, but so many things happened in that period of time that it was like a dream that almost never happened. So, where I was, at that moment ,right before I started writing Fonzo, I felt like I was where I started out, before I had my first movie. I was just in this bleak obscurity, where I was just trying to work on myself, but not knowing where to start, or where I wanted to end up. I had this a memory of something that I had read about Al Capone, years after he was released from Alcatraz, due to his illness that was getting worse and worse, and how he was just sitting in his own backyard, puffing on a cigar, right before his life ended. I wondered what it would have been like to have been Al Capone, dealing with those memories of his own heyday, and what it would feel like for him, if he flipped on the radio and heard a radio play about Al Capone, as a character being played by actors in these fictionalized narratives for situations that actually did really happen, and that he was there for and probably remembered very differently than the fictionalized, mythic account that was out there for consumption, for the public.

I just felt like I, on some very small level, connected to that. I had my own disastrous situation with Fantastic Four. There were all of these stories that were being shot out to Twitter and into social media, about me and in a light that I personally didn’t remember. If there was a plot to the story of Josh Trank that was being put out there, I didn’t remember it that way, but it was out there long enough that it felt like the public, or at least social media, had embraced that story of me. I started to question whether or not I was crazy and that maybe that is what happened. So, I was wrestling with all of these issues in my head. Once clicked into that, what if and what would it be like, about Al Capone, I just started writing it, as a way to resolve issues that I was feeling. Ultimately, what made it cathartic was knowing that, while I was writing, I was hoping that this story I was writing about Al Capone, at the end of his life, would be the beginning of my life, in a new way. This was the story of the end of his life, but it wasn’t the end of my life. Even though I felt, before I started writing it, that it was the end of my life, it was a reminder that this is not the end of my life.

It sounds like all of that was very intertwined, in the sense that, if you hadn’t gone through all of those things, this movie very likely would not have existed in this way, or you would have done something else entirely.

TRANK: Exactly. That’s why I’ve been saying that I’m grateful for everything having happened the way that it did, as crazy as that sounds. For better or worse, I’m obviously very aware of the reviews and I know that it’s a very polarizing movie, but I love this movie so much. It is exactly the movie I wanted to make. I could not be more proud of this movie, and I’m so excited for it to be out there to connect with all kinds of people, in ways that I’ll never be able to imagine. I’m grateful for that because I was able to make this film out of it, and connect with Tom Hardy, who’s one of my favorite actors and is now one of my best friends, and (cinematographer) Peter Deming, Linda Cardellini, Matt Dillon, Kyle MacLachlan, Noel Fisher, and this entire incredible crew that really became a family to me while we were making the film. I would have never experienced any of that, if things had turned out in a successful way on Fantastic Four. That world that I was in, at that time, at least to me, felt like a simulation of reality, as opposed to the very immediate, real reality that I’ve been in and that I feel inspired by and alive inside of now.

The Polygon article that recently came out was a great and comprehensive write-up about your whole journey. What was it like reading that, for the first time, and seeing that all of that laid out in front of you?

TRANK: A little bit shocking. I discussed with Matt [Patches], way early on, that I didn’t wanna be involved in any fluff piece and I wasn’t gonna sugar coat anything that I would have to say about anything. Four years ago, when we started that, I wanted to make sure that I could have, for myself, some kind of a time capsule that, years later, I would be able to look back on and maybe be able to understand myself a little bit better, back then. So, if I had been in any way, shape or form, disingenuous about how I felt in those moments, years ago, then what purpose would it serve me, right now, to look back on it. That’s where I came from to get to where I am now. So, I didn’t have a sneak peak at it. I read it, at the same time everybody else did. I read it and I was depressed. It was really a weird thing to read because it was so real. I forgot all of the things that I had talked about with him, so when I read it, it wasn’t like, “I don’t remember saying that.” It was like, “Oh, I definitely said that, and I definitely remember feeling like that.” There was a lot of anger in there.

The one thing that I hope, for anybody who’s read it and who’s had enough time to read it because it’s so long, is that everyone can accept the fact that this is the accumulation of four years worth of conversations, starting from a time where I was really just fried and angry and defensive. Where I’m at right now, I feel so far away from that place. I’m so happy with the work that I’m doing, and I’m like really close with my family. I’m a very different person now, and having been able to make Capone cleared so many skeletons out of my closet. I’m a much more calm person, so when I was reading all of these manic diatribes, I was just like, “Oh, god, that’s intense.” It was uncomfortable to read it, but it was real, and that’s good, I think. I wouldn’t want it to be propaganda. I want to really look at that. If it comes across polarizing, then that’s okay. I don’t have any control over that. My mom read and she was in tears because a lot of this stuff, she didn’t know about. I really kept my family out of the loop while all of that stuff was going on. I hope it’s a piece that can be informative to other people and to young people. It was for me, where I’m at. Every single one of us has had our own Fantastic Four in our lives. For some of us, maybe it just wasn’t a public thing. I’m sure you’ve worked on something, in your life, that just was an utter disaster and everybody came out looking bad, and it was a learning experience. That’s the way that I look at it. I don’t regret it, at all, because I needed to go through that, in order to have a more mature perspective, to be able to write something like this film.

How did this finished film compare to what you had originally envisioned for it, when you started working on it?

TRANK: It’s the same. It’s the script. It’s funny, it’s exactly the script that we all wanted to make. There’s very little difference.

How long was the first cut versus what we see now? Was it a lot longer?

TRANK: It wasn’t really that much longer, at all. My rough assembly of the movie might have been two hours and five minutes. In editing, you’ve gotta kill your babies, and I like to get that out of the way quickly. I don’t wanna linger too long on something that I ultimately know is gonna have to go. Those things were some of the more fantasy elements to the movie and the alternate reality of Alphonse, as a farmer in Tuscany with this boy and these lush scenes of them running around and being on tractors. It was something that I originally had in the film, running parallel to the main storyline. It was very beautiful and interesting, and El-P composed a beautiful, lush, very surreal and oddly dark score for it. But I ended up cutting most of that, except for just that little peek at the end ‘cause I just felt, as a movie, it created a pacing problem. I was afraid to cut those pieces out, for the longest time, and then, once I did cut them out, it was a relief because I didn’t need any of it. I wanted to just stay with this character, all the way to the end, as opposed to popping out to this other weird place. It felt like it was fantasy, but it was also a little bit too on the nose for what this experience needed to be.

I’m happy that I was able to make the movie the way that I wanted. If I had done this through a bigger studio, they would have wanted me to be more clear about it in the cut, so that audiences understand that a bit more. But my favorite movies, and the kind of movies I like and that are the reason why I want to do this, are the ones that have endings with ambiguous notes at play, and detours and culminations. One of my biggest inspirations, in my life, cinematically, is the movie Barton Fink, by the Coen brothers. That movie is utterly ambiguous, in so many ways, but also very literal and specific, in so many other ways. I’m by no means comparing this to 2001: A Space Odyssey, but as a template of ambiguity in cinema, if they had just explained it all, would we really care, some years later. We would be in awe of all of the visuals and the innovation behind all of the camera work and the modeling, but it’s those mysteries that leave us wondering, toward the end, that draw you back into the movie again, as you think about what it was trying to say.

Why has Barton Fink been such an inspiration for you? How do you feel that’s influenced you?

TRANK: I don’t know. It’s funny, I saw it when I was really young, like nine or 10, and the first thing that I liked about it, I was just so struck by John Turturro and his hair and the look on his face. It felt like a cartoon almost. He’s just so interesting to watch. Growing up in a very culturally, extra Jewish family, I was looking at this super Jewish guy with crazy hair. The way that he was navigating through this world in Hollywood, where you’ve got all of these Jews calling each other kikes was just mind blowing. You just don’t see that in a movie. I grew up with my family’s very deep history with the Holocaust. A lot of my dad’s family was killed in the Holocaust. My dad grew up in an extremely antisemitic area, as the only Jewish family on the block, in white bread suburbia in the 1950s. I grew up hearing tales of what it’s like to be called the k-word, so I remember watching that movie, and it was the first time I ever heard that word in a movie like that, and it was said by Jewish people who were calling each other that out of spite, as if to say, “How dare you be this Jewish?” It just painted my own understanding of Jewish identity.

I’ve continued to always re-watch that movie, over the years, as I grew up, and then started to connect to it on a different level, as a movie about a writer who just feels like he’s misunderstood, but also doesn’t understand that. He’s pretentious and his ideas are actually pretentious, and I love that about the movie. He isn’t this writer that’s gonna change the world. He’s a writer who wrote a play that got great notice of-Broadway, and Hollywood is here to give him his shot, to basically write a B wrestling picture. He goes into it thinking, “I’m gonna write this film that’s gonna be poetry and it’s gonna be bigger than a B-movie. I don’t care about the wrestling or the action. I want it to be this man who’s broken inside, and his relationship with this child and this woman that he’s trying to connect with.” He’s so passionate about it and he puts his heart into the script, and then the studio reads it and is like, “What is this shit? This is a wrestling picture. We want action. We want big men and tights, attacking each other in the ring. That’s what people are paying money to see.” After all of these months and months and months that he’d been pouring his soul into this, with the studio treating him like a king, kissing his feet and welcoming him into Hollywood, he turns it in and they’re like, “Get the fuck outta here.” The actor who plays the head of the studio gives one of my favorite lines where he goes, “You think you’re the only writer that can give me that Barton Fink feeling? I can get tons of writers in here who could give me that Barton Fink feeling. Get the fuck outta here.”

I’m paraphrasing, but after what I had gone through on Fantastic Four, I could identify with that. In the beginning of Fantastic Four, the mantra that I was hearing from the head of the studio was, “We want Josh Trank’s Fantastic Four. We want that Josh Trank/Chronicle Fantsatic Four.” And then, at a certain point, I started to feel like, “You’re not the only kid in town, who can give us that Josh Trank feeling.” It’s weird. I remember talking to one of my best friends, who I grew up with and we shared our love for that film, and we both grew up loving movies together, and I was lamenting on that and being like, “I feel like I’ve become Barton Fink, in a way.” In all of the times I’ve brought up Barton Fink, I’ve never brought up that, which I think ins pretty interesting.

When I spoke to Alex Garland about Devs earlier this year, he told me that he’d found a home in this more long form storytelling environment. Have you ever considered going that route and doing what is essentially a long indie movie for a streaming site, that you can make without studio interference or the oversight that you get on bigger movies?

TRANK: I would love the opportunity to do that. As far as what I’m working on currently, I’m working on a handful of things that I’m really passionate about. It’s nothing that I can really go into great detail on, not because of NDAs, but just because I don’t wanna set up any expectations for things. Before I get to the end of the first draft, sometimes what I’m writing might turn into something completely different. I love that exploration and experimentation of writing and that process. One of the things that I can mention, in just the briefest way, is that I’m working on this limited series that Tom Hardy is producing and that he’s involved in and he’s very excited about, and I’m excited about, is a story that spans decades, from right at the end of World War II and concerning the formation of the CIA, but from a point of view that hasn’t really been seen in a movie or in television before, and it just mentioned in books. It deals a lot with Castro and Cuba, and capitalism versus Communism. It’s really big. sort of the, you know, capitalism versus communism and it’s, it’s, it’s big. It’s really big.

Is that something that he’s looking to produce and star in?

TRANK: It’s for him to star in, as well.

Since doing Capone, have you guys been trying to develop things together, or is it just this one project?

TRANK: Everything that I’m working on right now, except for one thing that’s a spec thing that I’m just twirling around in my head, are all with Tom. Tom and I are doing a lot of stuff together. Maybe three months after he and I met, and at least over a year before we even got to pre-production on Fonzo, we were coming up with what we were gonna do next because we just have so much fun together.

If you could wave a magic wand and get a green light on a project tomorrow, what would you like to see made?

TRANK: It would be the CIA project. It’s really good. It’s interesting, it’s dangerous and it’s fascinating. The things I’m learning from it, it lends so much big commentary and parallel to how we ended up where we are now, and I’m fascinated by those things.

What do you enjoy about watching someone like Tom Hardy, who clearly puts all of himself into a role, and he really seems like he contributed so much to this character with his performance, and the look and sound and feel of it? What’s it like, as a filmmaker, to have someone like that to partner and collaborate with?

TRANK: He feels, to me, like a brother and a comrade. It’s hard to describe. On one level, you’re working together, but at the same time, you’re also really good friends and you have your own secret language, private jokes, and little ideas that we’re excited about. What’s cool about once he gets on camera is that it’s a lot more casual than I think one would expect. The work that he does when you say, “Action!,” is so intense and big, but that’s what’s really interesting about observing his craft. He has such a casual and immediate command over his skill, as an actor, that he can be fun and the human being that you know as Tommy, and then you call, “Action!,” and his face transforms and he just becomes that. It’s like watching somebody who’s your close friend, who also happens to be one of the most talented human beings, ever. It’s cool. I don’t know how to describe it. It’s just amazing.

He’s so good at it. He’s also very open and wants feedback. He’s not the kind of person who’s gonna do something that’s gonna exhaust him, so you’ll only get it once. He wants to know exactly what I think, and in a fun and collaborative way. There’s no insecurity with him, when he’s doing what he’s doing. It’s always coming from a place where, because he and I have such a good rapport with each other, and we’re both very candid and honest people, I don’t have any hidden agendas, when it comes down to talking to Tom, and he knows that. That’s why it’s very easy for us to collaborate together like that. He knows that I’m not screwing him over or trying to give him directions to purposely mislead him to do something that he doesn’t know about ahead of time. There are different ways of working with actors, and there’s a way that certain directors do what they do that I wouldn’t condone because I think you can get the same results by being transparent and collaborative, as part of a team effort, as opposed to being mercurial and a leading people blind down an alley.

Capone is available on-demand.