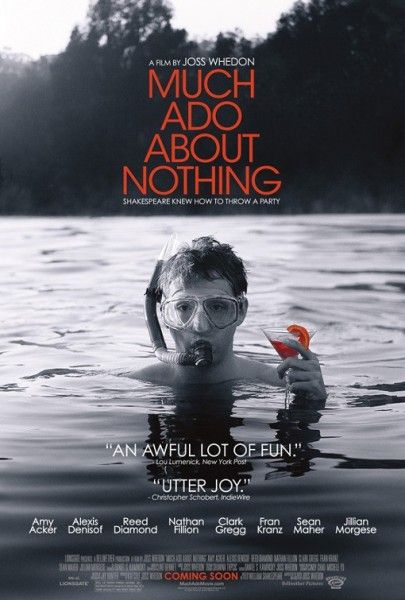

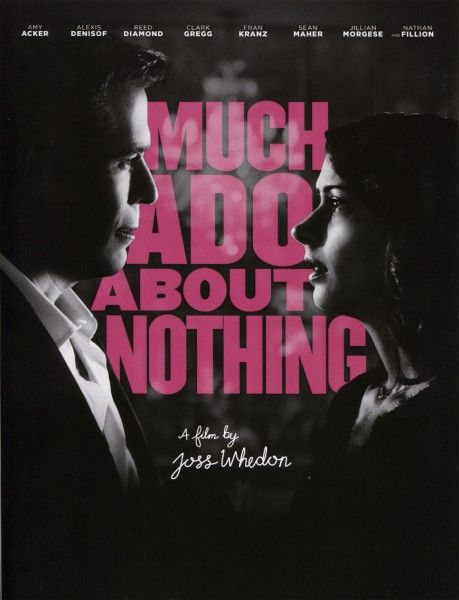

When Shakespeare meets Joss Whedon for Much Ado About Nothing, the result is a contemporary spin that was shot in just 12 days in his house. The story of sparring lovers Beatrice (Amy Acker) and Benedick (Alexis Denisof) is a series of comic and tragic events that offer a dark, sexy and, at times, absurd view of the game of love. The film also stars Clark Gregg, Nathan Fillion, Fran Kranz, Sean Maher, Reed Diamond, Tom Lenk and Jillian Morgese.

During this press conference at the film’s press day, co-stars Amy Acker, Alexis Denisof, Nathan Fillion and Clark Gregg joined Joss Whedon to talk about why Much Ado About Nothing out of all of Shakespeare’s plays, the advantages of doing this in black and white, delivering Shakespeare dialogue versus Whedon dialogue, why Shakespeare is relevant to today’s audiences, the rehearsal process, deciding how much of the original text to trim, and what they took away from the experience. Whedon also talked about going from doing a movie as big as The Avengers before switching gears to do a film as small as Much Ado, getting his dream cast, telling a story where no one dies, and the pressures of doing pop culture TV versus the classics of literature. Check out what they had to say after the jump.

Question: Joss, of all of Shakespeare’s plays that you could have chosen, what attracted you to Much Ado About Nothing?

JOSS WHEDON: I love Much Ado. It’s hilarious and it’s accessible, but it’s also very dark and it has a lot to say about love, not all of it good, and how we behave. It poses a lot of interesting questions. It doesn’t resolve all of them, even though it has a happy ending. It’s this open debate about the way we behave and the way we’re expected to. It’s fascinating to me. But, the short answer is [Alexis Denisof and Amy Acker]. That’s why I wanted to do it.

What challenges and advantages did you and D.P. Jay Hunter have, in doing this in black and white?

WHEDON: Well, black and white was my contribution, and making it beautiful was Jay’s. I felt very strongly that it if fit the narrative. It’s a noir comedy. The dramatic and the comedic elements are very much a mix, and it had an old-fashioned feel to it that I wanted to capture. And I couldn’t afford costumes, so it seemed like black and white was the way to go. And then, Jay was very influence by French and Italian new wave cinema, and also the older stuff. So, even though it was a very light lighting package, he made sure he used the sun and what little we had to give it that old-fashioned glamour, besides the fact that it makes everything pretty and takes away a lot of problems. Anything that doesn’t fit the palette, you don’t know about it. If someone shows up in an aquamarine dress in the background and you didn’t see it in time, it’s fine. You’ll never know. It gives the movie a little bit of a remove. It’s very casual and it’s very intimate, but at the same time, it’s film. That allows for the language to settle in, in a way that, if it had just looked like a home movie, it wouldn’t have.

What’s it like to act in a Joss Whedon project and work with his works, in comparison to what it’s like to work with the words of Shakespeare?

NATHAN FILLION: I don’t want to say that Joss Whedon is the Shakespeare of our generation. It’s true, but I don’t want to say it.

ALEXIS DENISOF: I’ve been saying that Shakespeare is the Joss Whedon of his generation.

FILLION: I think there’s a real poetry to Joss’ words. In the same way that you do not paraphrase Shakespeare, you do not paraphrase Joss Whedon.

AMY ACKER: This play has that perfect blend of comedy and tragedy, and Joss does that so well. That’s what makes being in his stuff so much fun, as an actor. He’s not afraid to take it in different places that you don’t expect it to go.

DENISOF: In the same way that Shakespeare was writing very much for his time, he was also unearthing observations that would last for generations beyond him. I hope I’m here to see that happen with Joss’ work. It’s true that he has got his finger on the contemporary pulse of American youth, but his finger is going a lot deeper than that.

WHEDON: That is the one that’s gonna get quoted!

What was your gateway drug into Shakespeare, that drew you in?

WHEDON: There are a couple of specific moments for me. Much Ado really was the gateway drug. I saw a beautiful production at the Open Air Theatre at Regent’s Park in London. They just nailed it, and it was hilarious. I was stunned by not just how funny, but also how contemporary and accessible it was. I had read Shakespeare and I was interested in Shakespeare, but it had never just opened itself to me, in that way. In that moment when Benedick says, “This can be no trick!,” with much authority, after the most obvious trick that’s ever been played, I was just like, “Really?! Shakespeare will do that? He’ll go that far?!” Something just clicked. I saw that production three times. Also, there was the Derek Jacobi Hamlet on the BBC. He is the Hamlet by which they’re all compared, for me.

CLARK GREGG: Much Ado was my gateway to the whole shebang. I was playing soccer at a small school in Ohio. I was a goalie and I dislocated my thumb, and they banned me from practice. I was walking past the theater and I saw some very attractive students walking in. I followed them, and there was an audition for Much Ado About Nothing. They fool-heartedly gave me the role of Benedick, and I delivered them a legendary Christmas ham. But I was hooked, so I immediately dropped out of that school and moved to New York, just ‘cause I loved it so much.

Nathan, why were you afraid to do this and how did you overcome that fear?

FILLION: I was afraid to do this project for much the same reason that I’m afraid to watch Shakespeare, which is that I will not understand it. That was stopping me from literally learning my lines. I didn’t understand what I was saying, until I sat down and studied, like back in school, what was being said, and what the pictures were that he was painting, and if I could comprehend what I was supposed to be doing. In much the same way as when I watch Shakespeare being done well, I got it. It was so easy.

Joss, how difficult was it to make a film as huge as The Avengers, and then switch gears and do such a small film as Much Ado?

WHEDON: It’s all the same job. It’s about, “Why is everybody here? What is the most emotionality and the most humor I can get out of this moment?” You’re in the moment you’re in, and then you’re in the next one. Trying to adapt Shakespeare is certainly as daunting as trying to make a superhero movie, but for different reasons. But for me, the level at which things are working doesn’t matter. It’s only about right now and, “Is this the most I can get out of this?” There isn’t really a difference. Although god knows it was lovely doing this after The Avengers, just because it was all so compressed. We accomplished so much, so quickly that you were fed back. It wasn’t like, “Oh, I’ll spend three weeks on one-third of a shot, and then give it to a house for six months, who will send it back complete.” With this, we just did it. It was like theater.

Why do you think Shakespeare is or should be relevant to today’s audiences?

WHEDON: The stuff he’s talking about is universal. I relate to it, as much as anything I’ve ever seen or read. The poetry of the thing is extraordinary, and it’s lovely to be able to interpret through that. What we’re talking about is love, identity, jealousy, pain and all the things that we still need to talk about. And you get Amy [Acker] falling down the stairs, so it’s a win-win.

What was your rehearsal process like for this?

ACKER: Some of us got to rehearse more than others.

GREGG: I came in a bit late. They had these Shakespeare brunches that I heard about. I came in quite late because of an issue with my schedule that then beautifully cleared up. I don’t know. I was quite daunted by the process. I had remembered, in that production that I was in, that Leonato was not a big part, but I was wrong. I had a lot of lines to learn quickly. At the same time, it felt perfect to me, that way. If I had had time to think about it, I probably would have over-thought it. There was something about the way things were just getting out of control for poor Leonato that really was served by just standing there. I also felt that the words are so magnificent. Not just because they’re pretty, because that misses the point, but they’re so active. You say them, and stuff starts to happen. I wasn’t really prepared for any of that, or where it was going. In film, a lot of people don’t want to rehearse too much. I wouldn’t have normally approached Shakespeare that way, even in a film, but I’m really glad it worked out that way.

DENISOF: The last thing Joss said to me when he proposed this crazy idea was, “You’d better know your lines.” That seems like simple advice, but it was fantastic advice. Looking back on it, I wouldn’t have wanted to waste any takes on not knowing my lines because we didn’t have very many takes. And he afforded us the opportunity to play these scenes from the beginning to the end, all in one take, which is such a rare treat on film. Anyone will tell you that you shoot a master, maybe, but who uses it? It gets chopped up with various angles and close-ups. The rehearsal process was about getting together in the same place, at the same time, for long enough to make it worthwhile. If you could get two people together, then there was a rehearsal. If Joss could be there, great. If he couldn’t, he would give you permission to carry on the process, and then he would meet with you, individually. And then, there was a lot of stuff being worked out on the fly, right before shooting it. But, it was his home and he had a vision of what he wanted to achieve. We all have complete trust in him. You could try something out, knowing that if it didn’t work, Joss would fix it.

WHEDON: And hopefully humiliate you.

Joss, how did you decide how much of Shakespeare you could trim, and did you do all of that ahead of time, or is there a complete version of the text somewhere?

WHEDON: Oh, I made all of those decisions before shooting. I think there are three lines that we cut. We did not have time to shoot anything we weren’t going to use. Also, I wanted to know the flow of the thing, as a film. I don’t like to create films in the editing room. Obviously, you learn something. That’s part of the process. But, I like to go in with very exact intent. It’s a very long play, and there’s a good deal of redundancy in the explanation of things. If I couldn’t find the heart of something, I would cut it out. For example, there’s Antonio, the brother of Leonato. I couldn’t find a reason to keep him in. He really would just come up and say, “So, here’s what’s happened so far, brother . . .” It’s like a Chinese menu. Everything is delicious, but you can’t use it all. It’s really, really long. It’s also very compartmental. You really can just lift whole bits. Obviously, you want to keep as much as possible of the stuff that’s the reason you showed up, and then only add, visually, what helps explain the emotionality of the thing. That’s what the very small, wordless scenes that I added were for.

Now that you’ve done Much Ado, if you ever have the chance to do another Shakespeare play, what would you want to do?

WHEDON: Most people don’t see Hamlet as an old bald guy.

DENISOF: I pitched that this morning!

WHEDON: Hamlet is the text that I’ve studied the most. No alienated teen ever gets over thinking that he is, on some level, Hamlet. There are others. Twelfth Night is the first that comes to mind. Hamlet, much like Much Ado, has that unity of place, where you’re trapped.

How was it to do something where nobody died?

WHEDON: It was fucking weird! I don’t know. I was like, “I don’t have any death. I’ll add sex!”

ACKER: Well, someone died and came back to life. You’re familiar with that.

WHEDON: That’s true. Hero died, if you’re some of the characters.

Apart from the dialogue, how much did you have the scenes planned out ahead of time and how much did you have to just do on the fly?

WHEDON: Everything was pretty well locked in. The one great thing was that the sets were built way before. When we rehearsed, we’d read it through, and then we’d go rehearse in the space, exactly how the space was going to be. We knew, “Oh, he’ll run down and try to do a balcony scene with her,” and “We’ll go from here to here.” Some of the physicality, we dialed in very specifically. A lot of it happened on the day, and that all came from the actors. Obviously, Amy didn’t say, “I’m gonna try something,” and then throw herself down the stairs. We did actually plan that one. We had the major parameters set up completely, and then within that space, we’d see what would happen with a shrub or a cupcake or a coat.

How much of the casting did you have set, when you decided to do this?

WHEDON: Well, I started with my leads. They were deal-breakers. I called them, even before I had finished [the script]. I called them before anything because I wasn’t going to do it without them. The next person I called was Nathan [Fillion]. I didn’t have a second choice on that one. I have this extraordinary stable of people. I wanted to make sure that I could find people who were available and who were right. I didn’t want to go to five guys and say, “Hey, you wanna play this part? Oh, you all do?! Shit!” It was a delicate process. There was a lot of me asking questions about where people were going to be for the next month, on specific dates. Clark [Gregg] was the most torturous because we wanted to make it work, and it wasn’t going to work. I went through three other Leonato’s, and then two days before production, I was like, “Are you still busy?” In every case, I got the person that I wanted the most to play the part. Honestly, you could do a Woody Allen in September and re-film this with another troupe of extraordinary people. I wouldn’t. I don’t want to. But, it’s an embarrassment of riches. I just had to make sure I didn’t piss anybody off. There’s not one person where I was like, “Well, they’ll do.” I got my dream cast.

Nathan, what was it like to do your scenes with Tom Lenk?

FILLION: What I’ve learned is that, if you want to be funny, stand next to Tom Lenk. I’m not a big prop actor, but if I could only have one prop for the rest of my career, it would be Tom Lenk.

What was it like to work with this Shakespearian language?

DENISOF: A lot of the stylistic approach had its roots in the Shakespeare readings that we were doing at Joss’ house, which were so relaxed and natural. Thank goodness he chose a play that’s primarily in prose. It’s not in iambic pentameter or rhyming couplets, so that allowed us to find our own rhythms and interpretations, and to have as much fun as possible and not feel that we were responsible for a poetry recital.

ACKER: Once you’ve learned the words, then you get to chew on these amazing words and they bring out the emotion and take the scene to places that, when you’re reading it, you would never think it was going to go. But, as that dialogue comes out and the poetry comes out of it, it really influences the scene.

What did you learn about yourself, or take away from making this film?

DENISOF: Maybe because of the short time we had, it was really an exercise of instinct. For me, it was a great chance to trust my instincts and hope for the best. I already trust Joss and Amy, and the rest of the cast, so in myself, that’s what I learned.

ACKER: It just reiterated how lucky we are that we have such great friends and we all got to do this together. We have this amazing friend (Joss Whedon) who has introduced us all and made it all possible.

GREGG: I have to say, I feel like it was a profound gift. I just went over to Joss’ house for dinner to see if he was okay, after shooting The Avengers. A couple of days later, it was, “Oh, you’re playing this guy.” To have someone not ask to see your Shakespeare license, or ask if you’d even done it in 20 years, it gives you a trust. I feel like the ripple effect that that caused made me go, “Well, I must be able to do it. He’s so smart. He wouldn’t ask me to do it, if he thought I was going to blow it, I don’t think.” It’s so deliciously empowering. You’re there and you’re like, “I don’t really know how to do this. There’s Amy. Look at what she’s doing. That’s just riveting and charismatic and simple. If I can just look at her, then I can do it.” I just felt like this whole organism was like a weird group hug, which was ironically the nickname that we had for The Avengers, on all of the secret documents. There was this weird Elizabethan group hug going, with this energy that was created. It was really magical. I feel like it’s a gift that stays with you and makes people want to do something like this for other people.

Joss, what are the pressures of doing pop culture TV versus the classics of literature?

WHEDON: The shooting schedules are very similar. Everything is the story. Everything is, “How much can I squeeze out of this?” They’re very similar because with TV, as soon as you’re locked in, you have a text, you have your sets, you have your cast. You know so much going in that you have the confidence to experiment in the structure of a very short shoot. That’s similar to this. Obviously, we all knew the text from various productions, and the actors knew it because they had learned it to say it. I had been studying it, so I felt very comfortable with it, and knowing that Shakespeare wrote it is a great comfort factor. At the same time, I knew the sets intimately and I knew that this cast was not only going to give me exactly what I needed, but they were all going to surprise me on the day, and make this thing alive in a way I couldn’t predict. If you’re doing a TV show that goes on and on and on, or you’re doing a play so famous that it could easily be presented as a stately home, it’s easy to forget that spark. The intent behind this, and the way I like to shoot anything, is to get the space ready, and then give it to the actors and let the electricity of a stage performance happen between them, in the moment. And that happened, all the time.

Is it true that you’re not an actor until you do Shakespeare?

GREGG: Sometimes you can do Shakespeare and you’re still not an actor.

FILLION: I say you’re not an actor until you’ve done Whedon.

Amy and Alexis, what do each of you like most about working with the other?

ACKER: That’s awkward!

DENISOF: Well, the holy trinity for me is Joss, Amy and myself, in a scene, so to get the chance to work with them is always my favorite day at work. With Amy, all you have to do is watch and listen, and it’s the same with Joss. That’s my approach. They’re so good that I’m just happy to be there, really.

WHEDON: Okay, Ringo!

ACKER: I’m pretty sure that anyone who’s done a scene with Alexis feels like he’s their favorite person to work with. I don’t think I’m special, in that way. There’s such a trust. He’s so smart and handsome and nice. Should I go on?

DENISOF: Yes, please!

WHEDON: I don’t think I’m like Shakespeare. Can we please make sure that that’s very clear?! Or if I am, it’s like he’s Frank Sinatra and I’m Frank Sinatra, Jr. That’s how we relate.

Much Ado About Nothing is now playing in theaters.