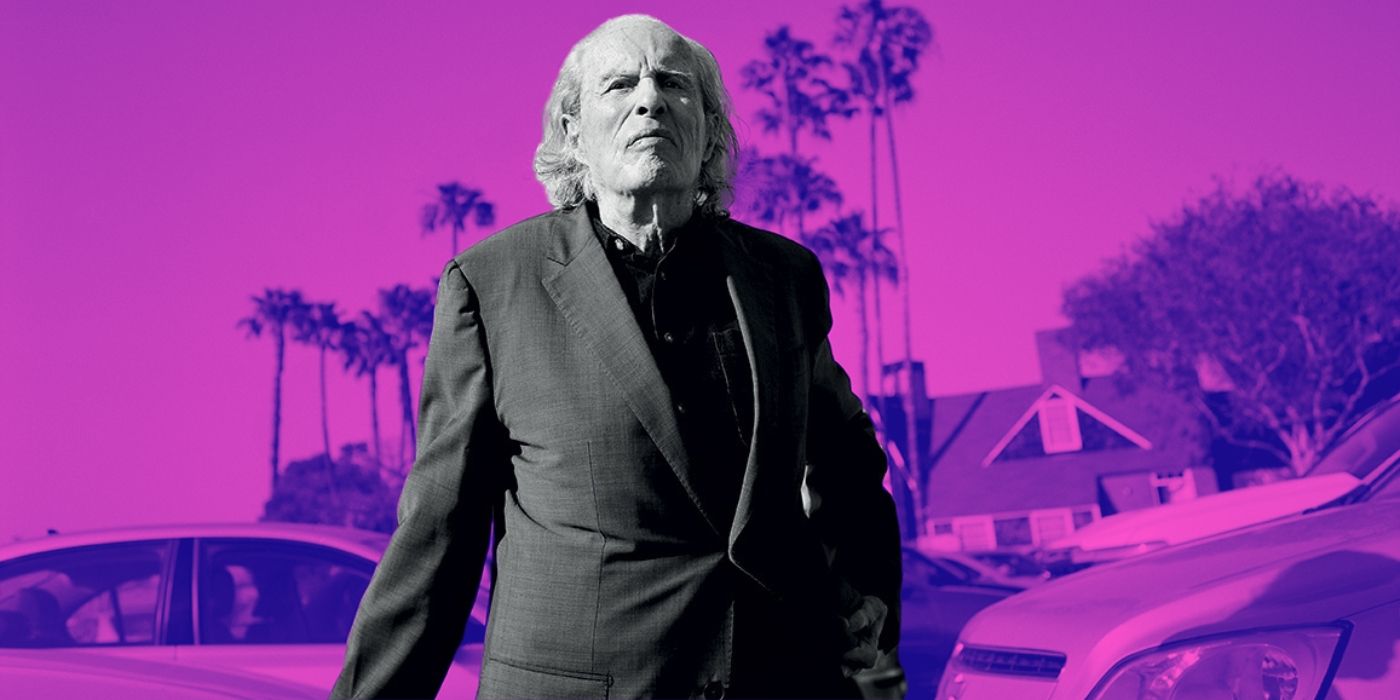

When Kenneth Anger died earlier this month at the age of 96, the world of avant-garde cinema lost one of its foundational artists, every bit as influential as Maya Deren or Luis Buñuel. He was far from a household name, but Anger seemed perfectly fine with that: he was a fiercely private person, and with each bold, surreal short film he made, he proved that he couldn’t be normal if he tried. He was not a filmmaker who bent toward the mainstream; he was a filmmaker who staked out his own position and allowed the mainstream to bend toward him. For some, Anger is best known for Hollywood Babylon, a filthy tell-all book that asserted, among other things, that Jayne Mansfield was decapitated in her fatal car accident, and that Clara Bow once had sex with the entire USC football team (including then-student John Wayne). It was written when Anger badly needed money and virtually all of it is made up; to give you an idea of the kind of journalistic rigor on display, Hollywood Babylon sourced one of its claims to a ghost. While many of its shocking “truths” linger to this day as urban legends, and it’s certainly no coincidence that Damien Chazelle named his debauched Tinseltown opus Babylon, a tawdry cash grab should not overshadow Anger’s seminal (in more ways than one) filmography.

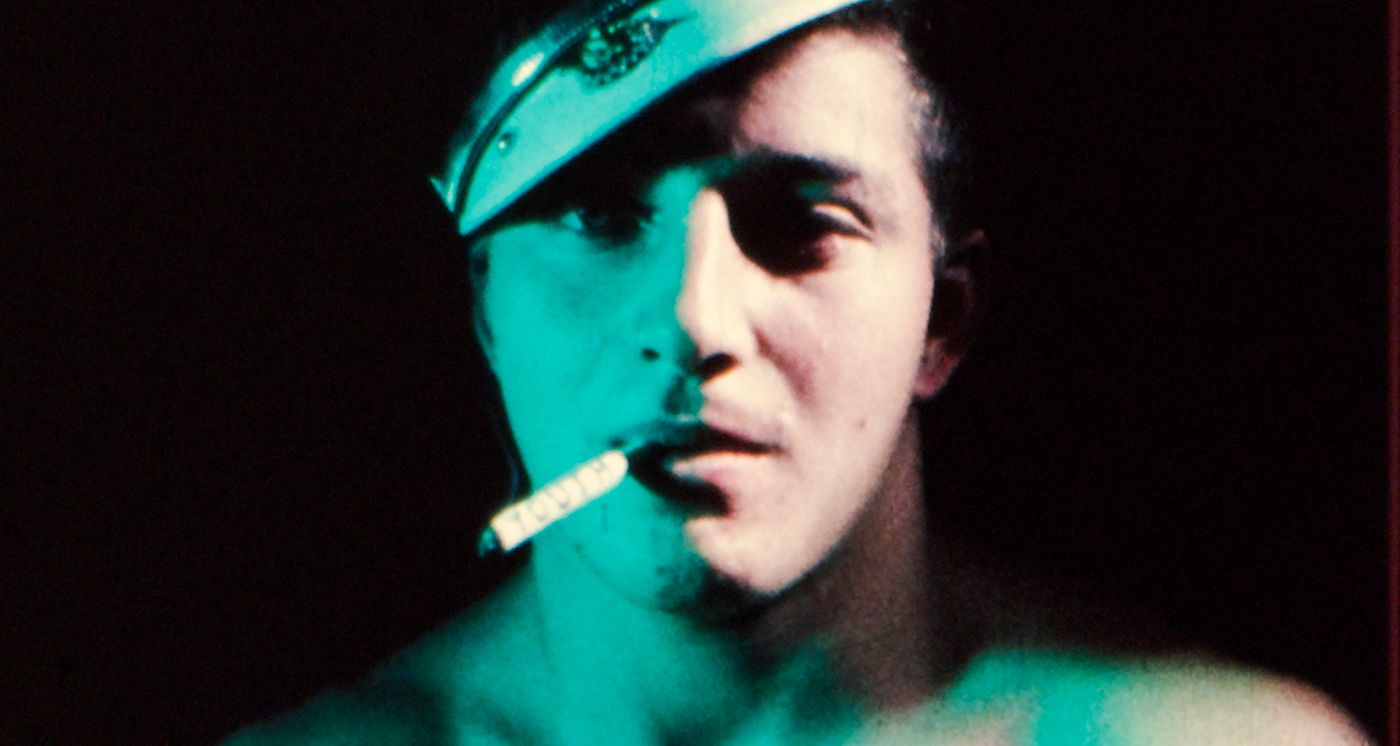

Kenneth Anger's 'Fireworks' Is an Early Queer Masterpiece

In 1947, Anger filmed his first major work, Fireworks, at his parents’ house in Beverly Hills while they were away for the weekend. The result was a film so bold and electric that it’s almost impossible to believe it was made just two years after World War II. With Hollywood operating by the studio system and the Hays Code in full effect, it’s easy for the modern viewer to associate older movies with wholesome, corporate-mandated innocence — which makes it even more shocking when they’re faced with Fireworks. At a time when homosexuality was criminalized, Fireworks was a work of brazen homoeroticism, with strapping young naval officers proudly flexing their muscles and bawdy, not-even-hiding-it symbolism. (You’ll never guess what body part a firecracker represents.) While Hollywood produced sanitized, inoffensive content, Anger captured raw sadomasochistic desire, with jarringly visceral shots of hands ripping open a man’s chest, faces howling in pain while being struck by chains, and the main character (played by Anger himself) being spattered with…something white and sticky. And on top of everything else, he starts the film with an expressionistic shot of a sailor holding a man in a position recalling the Pietà. It was an act of pure transgressive camp, and queer filmmakers like John Waters and Todd Haynes clearly took notes.

Kenneth Anger Made Perfect Use of Kitsch

Camp, or kitsch, is omnipresent in Anger’s work, as in so much 20th-century queer cinema. His films are filled with dramatic poses, decadent costumes, bombastic classical music, and clowns yearning in the moonlight to the strains of doo-wop. However, as David Pratt wrote in his review of an Anger short film collection in 2007, the filmmaker “possessed a prodigy’s mastery of the dynamics of film that enabled him to utilize both the images and atmosphere of kitsch without allowing it to interfere with his technique or cinematic sensibility.” On paper, the procession of mystical tableaux in 1954’s The Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome might seem grotesquely self-important; in practice, it’s hypnotic, with lurid colors and decadent imagery melting together in an intoxicating psychedelic swirl.

Anger was a lifelong occultist, and the full context behind Pleasure Dome is eye-wateringly esoteric, but the beauty of the film is that it’s ravishing no matter how much you know, or seriously you take it. Similarly, 1953’s Eaux d'artifice (a pun on "feux d'artifice," the French term for fireworks) could have been silly and insubstantial in a lesser director’s hands. But as Anger tracks a well-dressed woman through a labyrinthine Italian garden, the film crackles with mystery and significance. The monochromatic, blue-tinted photography turns sparkling fountain water into otherworldly flickers of light, and the feathered headpiece the woman wears seems to glow as she descends a flight of stairs into the garden. Her journey, in perfect rhythmic conversation with Vivaldi’s "Winter," leads her into that fountain, and the moment she disappears into the water sparks with that perfect blend of surprise and inevitability. Like a bursting firework, the water (Eau in French) allows this woman a sense of release; as critic Scott MacDonald suggests in A Critical Cinema, it is an “explosion of pleasure and freedom.”

'Scorpio Rising' Is An Avant-Garde Classic

Perhaps Anger’s best film, and certainly his most influential, is 1964’s Scorpio Rising. Set to a soundtrack of golden rock n’ roll hits from the '50s, Scorpio Rising starts by observing, in almost fetishistic detail, the way bikers maintain their motorcycles and care for their appearance. It both reinforces the James Dean/Marlon Brando myth and playfully subverts it, setting the mechanical tinkering of their beloved bikes to a coquettish love song about a wind-up doll before showing these men essentially putting on costumes. But little by little, Anger adds more off-putting details to the edit. The bikers’ behavior grows more aggressive and erotic, culminating in them rubbing mustard on some guy’s crotch. The main biker, the titular Scorpio, is associated with Jesus, then Hitler. A ritual starts to take shape, inscrutable to us outsiders. Soon, Nazi imagery grows more frequent; the lights become lurid and ominous; the comforting '50s music is interrupted by screams and roaring engines.

It all leads, as one biker’s arm tattoo reads, to “blessed, blessed oblivion.” As an artistic statement, it’s provocative to the point of antagonism — even today, Anger’s use of Nazi imagery rankles some. But not only is Scorpio Rising overwhelmingly potent in its own right, but it also casts one of the longest shadows of any short film from the 20th century. The DNA of Scorpio Rising can be found not only in the queer cinema of Waters and Haynes but in some of the most iconic media of the past 50 years. Its disorienting lighting can be seen in the work of Nicholas Winding Refn, an Anger devotee who interviewed the man himself; its surreal fragmentation of the ‘50s reminds the viewer of David Lynch; its perfect use of music, edited in time with the action but not old-cartoon precise, can be felt not only in Martin Scorsese's movies but the entire medium of the music video. With one film alone, Kenneth Anger’s place in the pantheon of American cinema would be secure; luckily for us, there’s so much more.