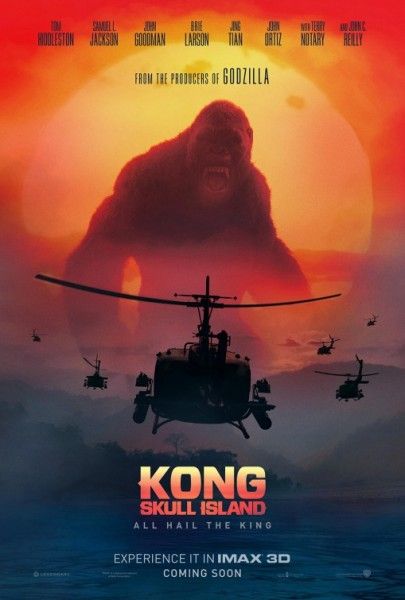

As a smashy-smashy, monster brawl, Kong: Skull Island is a reasonably good time. Kong is bigger, visual effects have come further, and director Jordan Vogt-Roberts and cinematographer Larry Fong know how to lovingly shoot the big guy raining down hell on anyone or anything that might get in his way. It’s a film that largely ditches the tragic and symbolic aspects of Kong beyond the most basic elements (he’s the last of his kind, he could kind of stand in for the majesty and brutality of the natural world) in favor of creating a rampaging monster movie, which is all well and good.

The problem is that Vogt-Roberts chooses to set his film in 1973, wants to live in the vein of Apocalypse Now, and comment on the Vietnam War without doing any of the real work such a metaphor requires.

The Vietnam War began in 1955, seriously escalated in the early 60s, and finally came to a close in 1975. Over 58,000 Americans lost their lives, and the loss was made even more tragic by two factors: 1) There was a draft in place, and it disproportionately affected those who could not afford to get out of service; and 2) it was a war with no clear goal and no sure way of achieving victory. Kong: Skull Island agrees that Vietnam was a “bad war”, but it only uses that insofar as to provide motivation for villain Preston Packard (Samuel L. Jackson), a decorated commander who knows that the was he was just in was pointless. When he comes across Kong, he sees an enemy he thinks he can beat and thus defeating Kong becomes a symbol for rectifying the wrong of the Vietnam War. It’s the thinnest, least interesting motivation possible, essentially reducing a Vietnam veteran down to an Ahab in search of his white whale.

If Vogt-Roberts’ had invested even half as much attention into dissecting the psyches and motivations of his Vietnam soldiers as he did into the visual effects and “Wouldn’t it be cool if my leading man wore a gas mask while using a samurai sword to cut down flying CGI monsters”, Kong: Skull Island would be worthy of its Vietnam War metaphor. But as it stands, the movie is exceedingly glib in how it processes war and tragedy.

In the 1960s and 70s, Vietnam fueled the American culture, and some of our greatest cinema is a direct response to a war that many felt was unjust and unnecessary. For Roberts, it’s a neat time period and provides a nice motivation for his villain choosing to go after Kong. Even though the film is set in 1973, the movie carries an attitude about how much it relishes the modern day. When Bill Randa (John Goodman) steps out of a cab and remarks on how Washington will never be more screwed up than it is right now, we can all have a good laugh because everyone thinks they’re living in the most interesting time.

Vogt-Roberts’ modern attitude surfaces even more clearly when the group finds Hank Marlowe (John C. Reilly) and he asks who won the war. “Which one?” they ask, and he replies “Figures,” as if his war, World War II, and the Vietnam War, are one and the same. I would almost be willing to accept that argument had Marlowe been a Korean War veteran (both the Korean War and the Vietnam War were fought ostensibly to stem the march of communism), but then he wouldn’t have had any reason to be fighting with a Japanese fighter pilot, get a samurai sword, and then there are no cool scenes with the sword. But Vogt-Roberts wants his line about how war is bad, and so he ends up equating World War II and Vietnam War as two products of a country that can’t stop fighting.

That attitude reflects a staggering lack of perspective, and while the thought process behind it may be well intentioned—the notion that all war is foolish—it simply doesn’t respect either conflict and the history involved in both. For Vogt-Roberts, these massive wars, which resulted in the loss of tens of thousands of lives, are cut from the same cloth, a notion that reflects a lack of thought on why these wars were fought and the consequences of those conflicts.

What’s more troubling is how the film wants to ride on the back of the Vietnam War and the Vietnam-inspired Apocalypse Now not for the purpose of dissecting war or trying to reappraise the conflict, but simply as fodder to get to the smashy-smashy action scenes. It’s the cinematic equivalent of doing skateboard tricks on the Vietnam memorial. It disregards history and the cost of human life in favor of wanting to show you something cool.

And because we’re over 40 years removed from Vietnam, he can kind of get away with it. No one would have thought to make a film like Kong: Skull Island in 1975 or 1985 because essentially you’re being careless about all those who suffered in that conflict. But as time starts to heal all wounds, the pain of Vietnam starts being lost in the national consciousness, and it becomes some stodgy thing from a history textbook, devoid of humanity.

To put it another way, let’s assume that Kong: Skull Island had been Kong: Skull Desert, and the plot is similar but it requires soldiers who are about to leave the Second Iraq War. Now imagine those soldiers getting stomped on by a gigantic ape or impaled by a giant spider. There’s no commentary about these deaths beyond showing the dangerous terrain, and we know these deaths are okay because they’re mostly happening to actors who don’t have their names on the posters. Do you feel comfortable with this movie? Or is its biggest problem that it’s too soon? Is time the only thing separating the appropriate from the inappropriate?

I don’t have a problem with blockbuster cinema using the Vietnam War as a setting. I don't have a problem with blockbusters engaging in wars, even if they're recent (Japan, the only nation ever attacked with nuclear weapons, was grappling with atomic power as early as 1954 with Godzilla). I don’t mind the Vietnam War being a setting at all, but it has to work holistically. A film like Tropic Thunder works because it lampoons ridiculous people trying to be taken seriously. It mocks the characters rather than the history. But for Kong: Skull Island, Vogt-Roberts never gives his metaphor or setting serious consideration. It’s a means to an end, and while the monster brawling is entertaining, I wish the director had chosen either a better arena or a better way to engage with the subtext.