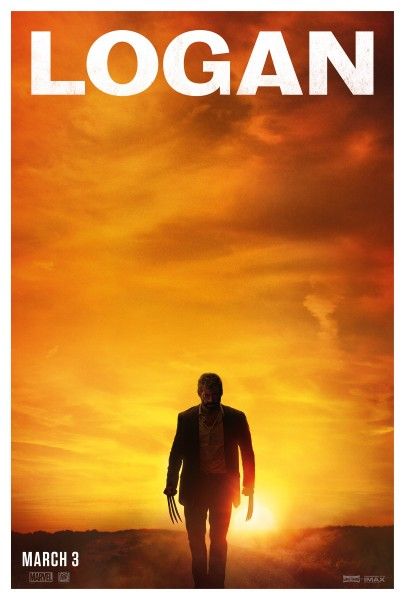

Just before the holidays, 20th Century Fox held a special presentation for their upcoming 2017 line-up.

We’ve already shared some of the footage that was shown, but clearly, one of the big surprises was when it was announced that they would be showing the first 45 minutes of the upcoming Wolverine movie, Logan.

While we’re not going to go frame for frame or into too much detail about what we saw, as to not ruin the experience, we can talk in general about what happens that differentiates Logan from the previous Wolverine films.

The movie opens with Hugh Jackman’s Logan working as a limo driver in Texas, clearly having given up being Wolverine. He has let his beard grow out fully, so he doesn’t even really look like Logan anymore. A bunch of street thugs try to rob his limo of their tires, so he fights them off, and we get our first signs that this is going to be a tougher, grittier character, using his claws in far more violent ways such as slicing off an attacker’s entire arm, literally disarming him. This was the first hint we got that the movie might be R-rated. (The other was when a woman partying in the back of Logan’s limo flashes her breasts.)

Early in the movie, we get our first look at Boyd Holbrook’s Donald Pierce, a longtime X-Men foe introduced as part of the Hellfire Club during the Claremont/Byrne run, but who later branched out on his own to lead a team of cyborg mercenaries called Reavers. This Pierce has the comic character’s mechanical arms but his gang doesn’t have the same robotic traits of the characters in the comics. This is another telltale sign that director James Mangold is trying to keep the new Wolverine more grounded. Pierce is clearly from Texas, going by his accent, which also helped to solidify the Western comparisons that are likely to be made due to the wilderness environment.

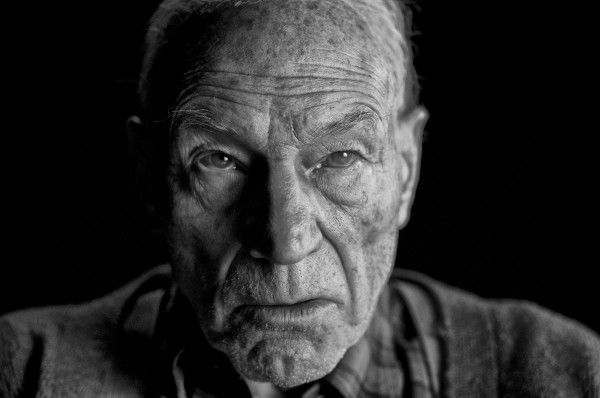

Logan ends up travelling down to Mexico, and there, he’s reunited with a much older, Charles Xavier (once again played by Patrick Stewart), who is in bad shape and living in a deserted building next to a downed water tank. Xavier is assisted by Stephen Merchant as a rather dilapidated-looking Caliban (the character was previously played by Tómas Lemarquis in last year’s X-Men: Apocalypse). Through their conversations, we learn that this story takes place 25 years after the last trace of mutants, the living ones having gone into hiding and no new ones having been found. If you know Caliban from the comics, his mutant power is to find mutants similar to Cerebro.

Logan soon encounters a young Mexican girl named Laura (Dafne Keen) travelling with her mother Maria, who doesn’t speak any English. (There’s a fun moment where we see that the girl is reading an X-Men comic with cover art similar to the animated show that shows how most people know Wolverine as a celebrity from these comic book stories.)

Pierce has followed Logan down to Mexico with his Reavers, and we get our first casualty among one of Logan’s allies. They’re also trying to get their hands on Laura, but they soon learn that the young girl has similar abilities that allows her to fight off Pierce’s men, including her own set of claws.

As the footage ends with Logan realizing that Laura may have some relation to him, the four of them pile into Logan’s car for a journey that will make up the rest of the film. That comparison may be why Mangold compared the movie to Little Miss Sunshine during a brief Q and A that followed the footage. He also mentioned that the idea of Logan is to explore what happens when a legend is made human.

The footage looked great, taking the gritty wasteland look of the Old Man Logan comics by Mark Millar and Steve McNiven, but not looking nearly as futuristic or apocalyptic as that or Mad Max. Besides the fact that the film is even more violent than 2013’s The Wolverine, it certainly looks like Mangold was deliberately going for more practical action and not relying as much on CG as other X-Men and superhero movies.

The cinematography by John Mathieson, who has worked with Ridley Scott and Guy Ritchie, looks so stark and compelling that Fox even handed out a coffee table book of random black and white images, although the introductory quote from the 1953 Western Shane might have been telling what some of Mangold’s other influences were.

The next day, Collider had a chance to sit down with Mangold for the following interview.

Collider: That was a nice surprise yesterday, getting to see 45 minutes of your movie.

JAMES MANGOLD: Was it a surprise?

I think most people thought you’d show a little clip or a couple things. I was expecting more like the Alien: Covenant presentation, because usually we’ll get two or three of the best bits, and you just showed the first 45, which is pretty impressive I must say.

MANGOLD: Yeah, I was actually taking a few notes about effects that needed to be touched up.

What I liked about it is that it’s definitely more practical than what we’re used to seeing in superhero movies. They’ve become so much about the costumes and FX and you don’t need that for this kind of movie.

MANGOLD: It's not even just a function of… the whole aesthetic of the films has become—I refer to it often as an arms race. How do you out big, out stakes the other guy? Well, at some point it's just not possible. The world will be destroyed. The world will be destroyed twice. The universe will be destroyed, the universe will implode. At some point, it all strikes me that in the end to make a narrative function, to make a movie involving, you have to be involved in the characters. The one thing all that spectacle does is gives you less time to investigate. It's almost just common sense as filmmakers now. I think, it's numbing. It's just loud, and it’s expensive, but we've seen it. Frankly, with the state of video games where they are, it's not even all that impressive anymore. You could live first person in a lot of these levels of destruction, in completely simulated worlds, so that when you go to the movie theater, I think what you're really paying for still is to have an emotional experience first. One thing on that level that a video game still can't give you is a kind of emotional journey where you really lose yourself in feeling.

I know Hugh's been talking for a long time about doing Old Man Logan, even going back to The Wolverine where he’d be asked what to do next? To actually adapt it from the comics faithfully would require all different things like other Marvel characters, but you took that idea and went in a different direction with it. What was the appeal of Old Man Logan and how to use it for your own movie?

MANGOLD: Well, the appeal of Old Man Logan was that Wolverine is a tricky character because he's essentially impervious in his prime state. It's very hard to create stakes or even generate an action sequence around a character, who will essentially heal from anything and is impervious to anything. There's always an attraction for me in figuring out how to debilitate him slightly. Just to make the story function in some way that he has a challenge with what he's facing. Beyond that, it's just so interesting, the idea of middle aged in a super hero, and kind of a life crisis. What was this about? Was it worth it? Did it all really happen? Did I make a difference? You keep saving these people, stopping villains and what does it yield? What does it get? It's just “Whack-a-Mole” at a certain point. To find a character like this in an existential crisis is very interesting. Plus there were elements of the artwork and the idea of Old Man Logan that were very liberating. Obviously, because of rights issues more than anything, we couldn't begin to tackle that story the way they did it, but it had a really profound influence on us, yeah.

You put Charles Xavier as a fairly big part of the story as well, and it’s interesting in that you had all these timeline issues with the X-Men movies that they used Days of Future Past to fix, but in this, you’re set 25 years later, so in which timeline is it?

MANGOLD: Well, honestly, I picked this year 2029 for the movie because I wanted to get clear of it all. I basically wanted to get past any known dramatization of anything X-Men on film so I could… I mean, if you're first setting out to do something different you can't also try to attach yourself and plug into every avenue of what exists or you're going to find yourself tied in knots. It was finding the little space for ourselves and we could get away from all existing films. Not reject them or completely push them away but simply give ourselves ... almost like talking about raising a child. Give ourselves our own space to grow and be what we want to be. Not be literally like a TV show picking up the baton from where the last one left off. That was my biggest concern. Also giving a space that the character could have gone some place surprising since we last saw him.

Because of the setting, you could also play with Western tropes, which you do in the movie and you end up with a Western that has these X-Men characters as part of it. You talked about some of your influences yesterday so was Mad Max in there at all?

MANGOLD: Sure, they're all in there. I think the interesting thing is--and maybe I'm being to academic--but I don't think there really is a genre called “super-hero movie.” I think that when you're taking apart these movies all day and working on them. Having made Westerns ... Westerns, I mean, Star Wars is essentially a Western, even more than it's science fiction. Whereas 2001 is science fiction. Blade Runner is science fiction. Or it meets noir in that case. Very often there are these different ... the Western is essentially and usually a very character-based clash of wills. Yes, there's these tropes of flatlands and Monument Valley and whatever that is, but the essential construction, what makes those movies so beautiful, is their simplicity.

I think where sometimes we fall astray when we're making comic book films or super-hero films is that we don't pick a genre to play. In a sense we think it is a genre itself but I don't think it is, meaning, what is the super-hero genre? In the past what would we be drawing from? Is it the talk of the clogs and togas movies in the past in a mythical sense? Is it the Ray Harryhausen movies? Is it the more action film, like Raiders? What are we drawing on or what are we mimicking? I think most successful films draw upon these certain dramas. Adventure, western, very simple clear lines and I'm a real fan of that. Meaning my thing is what kind of movie am I making? When someone says comic book movie that doesn't answer the question. There's 100 ways to make a comic book movie. Comic, noir, adventure, horrific, dreamy, surreal. These would all be ways to attack it and the word “comic book movie” never identifies one of those it would be. It doesn't make any sense.

Such as The Wolverine was essentially a samurai movie.

MANGOLD: That's absolutely right. You draw upon and I think you meet with the most success when you actually draw upon a template or an inspiration that isn't another comic book movie. That is essentially pushing and pulling you in some new direction. That's actually what I think the comic book artist do. They don't make a comic based on the last comic, they make a comic drawing from some far reaching inspiration that takes them some place new.

Wolverine is a great example of that, because Frank Miller took a different approach than Barry Windsor Smith in terms of the art, putting the character into different genres.

MANGOLD: I think that's what was important to me. We had to make a movie that we were inspired to make. I always think that we're going to make a better movie if we're actually fired up about what we're doing as opposed to just pulling a cord of pre existing decisions along the road. A sack of pre-existing decisions. Going what would we do. Hopefully an audience is going to enjoy another filmmakers take. The same way we'll go see Hamlet or something directed by four different people and have a completely different experience. There's a way to attack these stories new and reveal new levels of character.

One of the things we got out of seeing the first 45 yesterday is that this is obviously R-rated, but it’s also very serious, and there isn’t as much of the nudge-nudge humor that you had in the previous movie.

MANGOLD: I think there's more humor in the back half as stuff gets going. I think you're right. I think I wanted very much to make a dramatic film. If you cut out all the action then you'd have a working dramatic film. I felt like I had wonderful actors. My writing partners and I are all pretty good at what we do. I felt like why don't we construct a real grown up dramatic movie about these characters and that in a way some of the wink-wink to me becomes about being a multi-checkbox movie that is trying to be for 8 year olds, 14 years, 19 year olds and 30 year olds all at the same time. That was for me the biggest attraction of making an adult rated movie was that in a way you're also redefining who you're making the movie for and you're not trying to offer both sushi and cotton candy at the same time, if you will. That you're clearer who you're playing to.

I want to ask about the girl Laura, who correlates to X-23 in the comics. You took a very different approach to her. First of all, she's younger, because I remember her introduction in the comics was very dark, and it involved drugs and prostitution.

MANGOLD: Well, that's not her origin story, the NYX (comics). Craig Kyle and Christopher Yost wrote an origin story with her as a child in the lab. There are comics. The cover art is her in a lab with her claws clawing against… Look up X-23. You're going to find images of a kid about Dafne's age. You're going to find an origin story about a kid that young. That really attracted me for a number of reasons. What you're getting at is why that age? I wasn't, while I'm pointing out is I don't think I was actually bucking any comic. I mean, all of those things you're talking about could lie ahead for this character. But that my real interest was in a father daughter story and a grandfather father daughter story. Meaning making that illusion to Little Miss Sunshine yesterday. It wasn't to me entirely comic. It was the idea that I really wanted to make a family film. Not a family film in the rated G sense--a family film in the sense that we're exploring the politics, pain, disappointments, and hopes we all face in family. And that in Logan being suddenly challenged with this child when he's avoided almost all human emotional entanglement at this low point in his life, and that Charles at this late twilight moment of his life is suddenly given a chance to reach out and help one more mutant. The idea that this mutant—as Dafne was 11--to me was really inspiring in the way that I thought it could affect the drama and keep it from being another CW show with another really hot person with claws jumping around. The idea that the relationships were purely about family was really interesting to me.

What we saw of her in action was pretty bad-ass.

MANGOLD: She's an amazing kid. Wait until you see the back 18 of the movie. She goes places you won't believe.

Logan opens nationwide on Friday, March 3rd.