There’s an archetype in popular media of the “hopeless romantic” guy. He’s sweet, he’s sensitive, and he will go to any lengths to win over the girl of his dreams, who is just one big, romantic gesture away from falling head over heels for this dude. It’s a familiar character and also a toxic one. It’s predicated on the notion that niceness is something to be rewarded as well as a tool one can use to make women swoon rather than just being good for the sake of being good. This character is always a heterosexual guy, and he’s been held up as heroic rather than a creepy stalker. And with Love, Simon, a mainstream movie finally recognizes him for the loathsome grotesque he has always been.

Spoilers follow for Love, Simon.

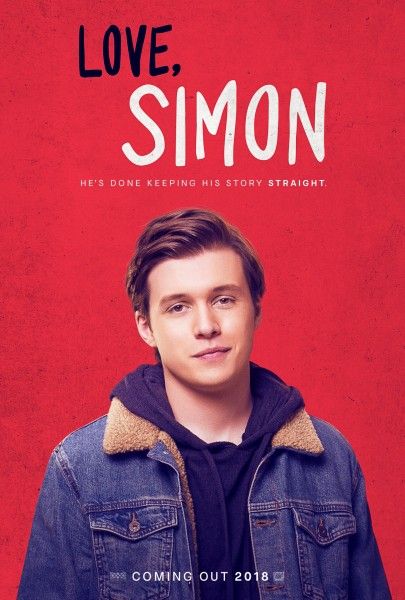

In Love, Simon, Simon (Nick Robinson) is a closeted gay teen who meets another gay teen at his high school online. Neither knows the other’s true identity, so they strike up a rapport through e-mails. However, when Simon accidentally leaves his Gmail open on a school computer, it comes across the creepy Martin (Logan Miller). Martin is infatuated with Simon’s friend Abby (Alexandra Shipp), and he agrees not to out Simon in exchange for setting him up with Abby. He’s the closest thing the movie has to an out-and-out villain even though his primary goal isn’t to thwart Simon.

Where Love, Simon gets really interesting with regards to Martin is that he treats the movie like it’s his story instead of Simon’s. While we’re all heroes of our own stories, it’s rare to see a supporting character in a coming-of-age story believe they’re the protagonist. But in a scene at a Waffle House, he listens to Abby’s personal struggle regarding her father and then launches into a tirade about how she’s a superhero. He stands up and loudly announces that Abby is a superhero and won’t stop until she echoes it. In one of the movie’s few missteps, she goes along with it rather than telling Martin to sit down and shut up.

Later in the film, Martin interrupts the National Anthem so that he can profess his love for Abby at a football game. In another movie, this would be his big, triumphant moment, and you can feel a modicum of pity as he assumes it will work out for him just like it worked out for every other guy in a movie who made a grand romantic gesture and got the girl. Except when Martin makes his gesture, it blows up in his face. People laugh at him, and Abby (whom he hardly knows) politely lets him down. Martin is not the hero of this story, and Love, Simon lets him know it.

While the movie could go further in obliterating Martin, who is really quite awful, and especially in having Abby not give him the time of day, at least the movie is on the right track with how we should treat this character. Look back at the 1998 teen comedy Can’t Hardly Wait, and that movie works pretty well outside of the Preston (Ethan Embry)/Amanda (Jennifer Love Hewitt) relationship. It’s bizarre watching this movie because Preston has put Amanda on a pedestal but doesn’t even really know anything about her. But for Can’t Hardly Wait, Preston isn’t a creepy dude who has endlessly fantasized about a woman he never found the courage to talk to; it’s about that guy waiting patiently and being rewarded for his bad behavior.

Plenty of other movies have followed suit, but Love, Simon lets us know that we should be done revering this character. We should have been done a long time ago, but his persistence makes sense. In the real world, his actions are repulsive and creepy, completely disinterested in the individual he’s wooing, yet wholly dependent on her reaction. But in movies, he usually wins because it’s a big, dramatic gesture and movies reward big, dramatic gestures. Provide an impressionable young guy in the audience who doesn’t understand the difference, and you get someone who thinks that the dramatic action is good rather than the action is good for movies because it’s dramatic.

Archetypes exist for a reason, but some need to be relegated to the dustbin of history. We don’t need Martins who think they’re the nice guy heroes who deserve to “get” the girl (and make no mistake, it’s absolutely about possession rather than affection). We don’t need mopey “nice guys” who do terrible things like blackmail their fellow students because the ends justify the means. We don’t need these characters because they’re not heroes, and it’s a credit to Love, Simon that it recognizes this archetype as a villain.