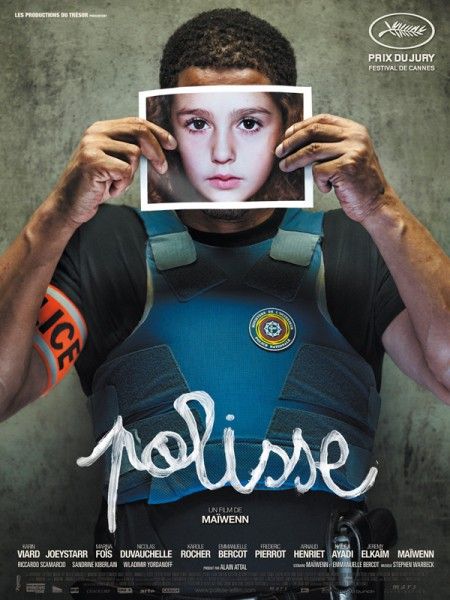

Basing her richly textured script on real child investigation cases, co-writer/director/co-star Maiwenn has gathered an accomplished ensemble cast of French actors---including Karin Viard, Marina Fois, co-writer Emmanuelle Bercot, Nicolas Duvauchelle, and rapper-turned-actor Joeystarr---who convey the emotional strain of the Parisian police Child Protection Unit’s work with gritty realism. With each new case, confession and interrogation, the tightly knit team of men and women face an uphill battle against both criminals and bureaucracy in this sharply written and well acted crime drama.

We sat down with Maiwenn at a roundtable interview to talk about Polisse which won the Jury Prize at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, was nominated for 15 Cesar Awards (including two wins), and was seen most recently at the Tribeca Film Festival. She told us how she researched her story to construct an engrossing narrative based on real events, how she handled the delicate scenes involving children to elicit some very naturalistic performances, and why she decided to play a supporting role in the film. The actress, screenwriter and director also discussed how she discovered during the editing process that working within the constraints imposed upon her by la DDASS, France’s equivalent to the U.S.’s Child Welfare Services, led to one of the film’s most riveting scenes. Read the interview after the jump.

Here's the trailer if you haven't seen it:

Question: Can you talk about the challenges of editing this movie?

MAIWENN: The editing took six months. It was quite easy in the sense that we respected the script and we haven’t changed the structure with the editing. My last movie, All About Actresses, was more difficult in terms of editing.

Did you do research to find out what a Child Protection Unit was like?

MAIWENN: Yes, of course, I did a lot of research before writing the script. I did an internship.

How hard was it to be accepted by the police in the CPU?

MAIWENN: Some of them were quite rude to me and suspicious about my possibility to make a movie. First of all, I’m a woman and a woman with policemen is quite difficult. But I’m used to it. As soon as you have power and you’re a woman, you have to deal with men’s attitudes, but it was okay for me.

Can you talk about casting yourself in the role of Melissa, the photographer, who’s documenting the work of the CPU? Is that an actual function that exists within the CPU?

MAIWENN: Well sometimes there’s a photographer, sometimes there’s a cameraman or journalist. I decided to act this part because it was the way to help the audience to identify. It’s the continuity of the normal spectator -- I mean, the way she thinks, the way she looks at the Child Protection Unit, it’s the way everyone watches when you discover a documentary. It’s the same point of view.

So she’s a link between the audience and the film?

MAIWENN: Exactly.

Was that a way for you to get into the story and write it by having a character that resembles your experience of discovering what was going on in this unit?

MAIWENN: Not really. It’s a fictional part. In reality, I was not like Melissa in the movie. I was much more the leader and involved, engaged, asking questions all the time. But I didn’t want to put that into the movie. I didn’t think it would help the subject.

What was the biggest challenge you faced making this?

MAIWENN: The biggest challenge was to not fall into the facility of treating it as a melodramatic subject. I didn’t want to do that, and I didn’t want to portray the cops as heroes and the children as eternal victims and the pedophiles as mean people. No, for me, that is too easy. I wanted to communicate the emotion that I felt when I did the internship. The emotion that I felt involved so much empathy for the pedophile. Of course, I loved those cops, but sometimes I was upset with them. I thought they were racist sometimes or homophobic. For me, they are not heroes, but in the same way that pedophiles are not mean people. They are just sick people. So, I wanted to convey this type of feeling throughout the movie.

The life of the members of the CPU is completely centered on their job which they take home with them. Do you see parallels with your life as a filmmaker and is your job equally all consuming because of your vision and desire to tell a story?

MAIWENN: Yes, it is. It is my passion to direct movies. I wouldn’t compare my job to them. When they have to deal with one case, it involves two days of police custody of a suspect and all the process of the investigation. Of course, it wouldn’t be appropriate for me to compare that to my job, but in the sense of the emotional involvement, [it’s similar]. By the end of the day, I felt they couldn’t just say “Hey colleague, goodbye. See you tomorrow.” Instead, they would say, “Okay, let’s get a drink, let’s take a break.” They needed to talk about the cases. And that’s the same for me. At the end of the day, on the set, I cannot just say bye to everyone. I need to have a beer and cool down because I’m so involved emotionally. In a different way, I am very involved in my job and my job is my passion.

In the U.S., if someone is convicted of being a pedophile, that person is not allowed to live near a school, and wherever they go, people are notified. Is it the same in France?

MAIWENN: I don’t think there is a system like that [in France]. I’m not sure. The police could give you the right answer. I don’t think it’s a good way to process [a pedophile]. In France, we have more respect. I mean, they give them a chance.

When you set out to cast the movie, what were you looking for?

MAIWENN: Most of the time, I wrote for the cast that I knew, for the actors that are in the movie like Joeystarr, Karin Viard and Marina Fois. I worked for them. I was looking for actors who look popular in terms of the way they talk, their voice and their temperament. They had to be popular. I didn’t want them to look like intellectuals. I wanted them to feel like they came from the streets.

The child actors had to talk about some pretty uncomfortable things. How was it to work with them?

MAIWENN: First of all, in France, we have an institution called la DDASS (the equivalent of Child Welfare Services here in the U.S.) that takes care of and protects all the children that are engaged in theater, commercials and movies. I think France is the country that is so rude to kids when they are working. I had to wait such a long time to get permission, until they said yes. I had to change the script, remove some dialogue and some scenes, so it was a really long process. And then, as soon as I got permission, it was because I removed scenes and dialogue that were too rude. When I met them, the institution, they explained to me that a child could have a problem when he becomes an adult if he does a movie with intimacy problem. They gave me this comparison: if the child is doing a horror movie in which he sees his mother decapitated with a chainsaw, it’s okay. No problem. I was like “Are you sure?” and they said “Yes, that’s the law.” I didn’t have any choice. I had to take out some dialogue and scenes. So, I did it, and my producer asked me “Are you sure you’re going to do what you promised to do?” Because la DDASS asked me sign a contract and state: “Yes, I’m going to shoot what I put in the script and I’m not going to do something else.” My producer asked me “Are you sure you’re going to follow exactly what you promised to do?” I asked myself what am I going to do? Either steal some words from the kids or some scene? I said to myself I think the institution is wrong. I think the kids know what they are doing. They know that this is fake. They know that this is cinema. But, I cannot take the risk. As a mother, as a human being, if, for example, I tell a kid “Okay, you’re going to say ‘Suck my dick’ but it’s not in the script. Don’t say it to your mother,” and 20 years later, I hear that the child had problems, I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror.

So I said to myself, I’m going to follow the script that I wrote. When I finished the shoot, I was in the editing room, and for the first time, I said to myself, la DDASS helped me out because I haven’t shot what I wanted to shoot. I haven’t used the dialogue that was rude. But I figured out that the imagination of what you do not see on the screen is more powerful than what you do see. For example, the scene in the gymnasium restrooms, at the beginning we were filming the child doing a blow job, but of course I wouldn’t ask the child to do it. I wanted to put the wig into the frame and see the head doing that. But, la DDASS told me I could not do that because the audience is going to think that the child did do the blow job. So, you cannot do it. I said to myself, when I started editing this scene, hey, it’s better. It’s better because we know something happened right before, but we don’t know what exactly. Your brain makes you freak out because you haven’t seen things. As a director, I learned so much because of that. I discovered that the less you show, the more powerful it is.

You got some terrific performances from the children, how did you approach directing them?

MAIWENN: I think very simply, I was lucky. I didn’t do anything special that I could say to you now. I just told the truth to the kids. “Hello, it’s going to be tough. You know it’s fake. You know it’s cinema. Your mommy’s there, but I’d rather your mommy stays in another room because I think it’s complicated.” I had a psychologist following me all day long. He was like a cop for me. I also had to deal with someone who represents la DDASS who was checking to see if I was following the script. But, I am a mother, so I’m used to talking with kids, and I knew them a long time before the shoot. I met their parents just to make sure they had confidence in me. When I felt that the kids were pushed too much by their parents, I wouldn’t take them. I was a child actor. My mother used to push me too much and I know the circumstances all too well. I chose the kids that were authentic and not too much actors because you can meet even very young kids that are already actors. They’re like seduced. But the main answer is just that I was lucky. When I saw other shoots where there are kids, I noticed that everybody is like [happy voice] “Hello! Disneyland! [singing] La la la la la…” and the kids are like “Yes?” They don’t like all this bullshit. They just want to have it be fun. So, it has to be short, otherwise, if they have to wait too much, they get bored. When the kids were on the set, we had to go fast. And, when the scene was not good, I was like “Hey, honey, it’s not good. We have to do it again. Are you ready? Are you okay? I want you to cry. Is that okay for you to do that? If you don’t know how to cry, think about this situation.” I would never say “Imagine your daddy is touching you” or stuff like that. Even with the adult, I never go to the intimacy. I think the secret is the way you listen to me and the way you listen to the script. Also, the funny thing is, when I was doing the casting with the kids, I wanted to be sure that they wanted to act and not the parents. So I asked “Why do you really want to be in this movie?” And you know what, all of them, the kids that I loved, they all told me “Because these are true cases.”

Were these all real cases?

MAIWENN: All the cases that are in the movie are true. Either I saw the cases, or I read the transcripts, or I saw the video, or cops told me about the cases. In the script, the first pages were really clear. In the movie, there’s a black title card that announces that these are true cases. Even if kids are young, they are already politically involved.

Was the film’s ending also from a real case?

MAIWENN: The ending comes from a true case except that she was not a cop. She was working for the institution that defends a child’s welfare so she was not a cop. But, I changed it and made her a cop because I felt during my internship that all the cops were so close to the edge, fragile and vulnerable.

What would you like an audience to take from this film?

MAIWENN: I know this movie on paper looks dark and I understand when people say “Sorry, I didn’t want to see your movie because it’s too emotional for me.” But I feel that all the people that saw the movie, at the end they said “Oh that’s not what I thought. This is funny. We came out of the movie and we were asking ourselves questions.” I like when people say, “When I came out of the movie, I wanted to take my kids with me.” That’s it.

What’s going to be your next project?

MAIWENN: I don’t really know.

Polisse opens in Los Angeles and New York on May 18th.