Mank, the new movie from director David Fincher, is a delicate dance between a love letter to the complexities and outsized personalities involved in Hollywood’s Golden Era, and a searing indictment of how powerful media titans warp public perception to further their own ends. On paper, Mank should be my favorite film of the year. It’s from one of my favorite directors, it deals with one of my favorite eras of history, and if you follow me on Twitter, you know I’m far too interested with political media, especially given the events of the past four years. And yet Mank left me oddly cold despite its magnificent craftsmanship, purposefully disjointed narrative, and rich subject matter. To be fair, most Fincher movies improve on repeat viewings, but on its initial outing, Mank plays like an immaculately crafted, anticlimactic screed against our current condition awkwardly married to a story of Old Hollywood.

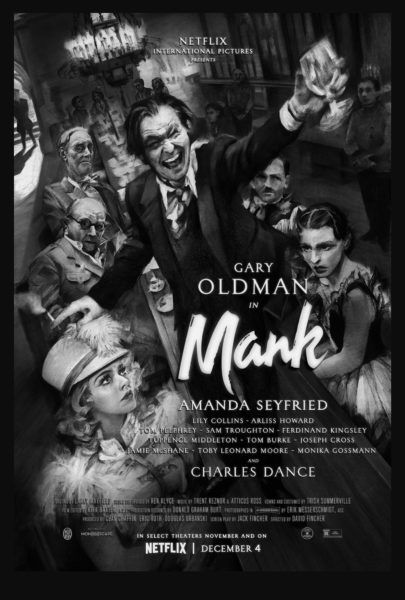

Sequestered in a rehabilitation resort following a car crash in 1940, alcoholic screenwriter Herman J. “Mank” Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) sets to work on writing a screenplay for hot shot young director Orson Welles (Tom Burke) for what will eventually be Citizen Kane, generally regarded as the greatest movie ever made. While Mank slowly chips away at the script with the help of typist Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), the film flashes back over the previous ten years to see a drunken but employed Mankiewicz working at Paramount and then MGM while ingratiating himself to the powerful media magnate William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) and Hearst’s lover/actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried). As the storyline of 1940 shows the solitary development of Citizen Kane, we begin to see why a self-destructive raconteur like Mankiewicz would bother going after Hearst in the first place.

Those looking for a movie about the development of Citizen Kane will likely be disappointed and would be better suited watching the 1999 TV movie RKO 281. Fincher, working from a screenplay by his late father Jack Fincher, is far more concerned with the lonely, confused, demanding process of creative writing, and seeking to push it further than just a montage of a writer angrily pounding at the keys of a typewriter. The main question of Mank isn’t “How did Citizen Kane get made?” but rather “Where did the idea for Citizen Kane come from?” which in turn makes Mank its own form of Citizen Kane where the discovery isn’t the meaning of “Rosebud,” but rather why Mankiewicz chose to focus his energies on Hearst and to a lesser extent Davies and MGM head Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard).

This bifurcation is beautifully realized in the way the film is shot. While seeing Citizen Kane before Mank isn’t mandatory, you’ll have a greater appreciation for Fincher’s craft and technique when you can clearly see how he’s echoing the style of Welles’ seminal picture. From its stark lighting and deep focus techniques, Fincher consciously foreshadows the film to come by depicting Mank’s writing process in that manner. These visuals are juxtaposed with the flashbacks, which, while still handsome and gorgeously constructed, don’t evoke Kane in quite the same manner.

As one would expect with a Fincher movie, there’s no flaw to be found with the craftsmanship. The cinematography is gorgeous, and those with HDR on their TVs will be stunned by the black-and-white photography within the first five minutes. Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross have delivered another incredible score for Fincher (their fourth for the director since The Social Network), evoking the music of the era while never sliding into parody or pale imitation. The 1930s-40s influences are unmistakable, but they help bolster the boozy attitude of its wayward protagonist. Special credit also goes to Fincher’s longtime editor Kirk Baxter, who not only weaves the timelines together beautifully, but also handles complicated crowd scenes with maximum efficiency.

And yet for all of its meticulous detail and fine craftsmanship, Mank is a distant affair because the characters and their relationships rarely resonate. It’s not that any of the actors are “bad”, and some, like Seyfried, turn in some of their best work. But the relationships they depict are oddly detached. Characters don’t talk to each other; they banter at each other, and while it may echo the style of 1930s Hollywood cinema, it’s a shade too far in the direction of homage because it comes at the expense of the film’s emotional center. When Mank is arguing with his brother Joseph (Tom Pelphrey), there’s no texture to that relationship. When Mank feels disappointed by Marion, there’s never a sense that anything has been lost. The characters shine their brightest not when they’re interacting with someone, but when they’re given over to monologue or self-definition.

The lack of warmth extends to the rest of the picture, and while no one can accuse David Fincher as being a romantic, you can see Mank as conflicted between a hazy appreciation of Golden Era Hollywood and disgust at how its greatest foibles continue to preserver today. This leads to a weird contrast where on the one hand, we get to share in Mankiewicz’s jaded view of the studio system, while also participating in his anger and indignation that someone like Louis B. Mayer would so gleefully serve as handmaiden to a propagandist like Hearst who cares only for the perpetuation of his own power.

When the film follows the machinations of Hearst and how Mank serves as witness to his own insignificance, the film feels particularly modern and addressing our current era where someone like Rupert Murdoch can funnel propaganda to millions of people to support his personal political preferences. And yet that aspect feels fairly obvious, so the film is always stronger when it approaches that political reality from Mank’s guilt and desire to atone for playing court jester to cruel kings. But even here, the film never quite lands the emotional heft it needs to really make you feel for Mank past the trope of the “damaged man with a heart of gold.”

Like with most Fincher movies, there are loads of interesting ideas swirling through Mank, and one of my biggest disappointments with my viewing experience is that I was left alone with the movie rather than being able to discuss it with my fellow critics following a screening, but that’s just a sad reality of life in the time of COVID. However, it’s also a movie I kind of wanted to just sit with despite its anticlimactic ending where we’re teased with a Mankiewicz/Welles collaboration that never happens. Mank is about a lot, and there are times when it feels like a lot, and yet for all of its ambition, there’s something missing at the center of the picture. The emotional punch never lands, and so while Mank has no problem earning the viewer’s respect, it struggles to find our adoration.

Rating: B