Every so often, there is a film that resonates with you on a personal level. It finds its way into your very soul, leaving an indelible mark the more time passes. It is a blessing and a curse, forever shaking you in ways that a story should while also leaving you unable to forget it.

A quietly devastating look at the aftermath of an all too common horror of American life, writer-director Fran Kranz’s debut Mass is one such film. It has been one that I have, for better and worse, consistently returned to. I have found myself watching it over and over multiple times, even as it was just released in October. It struck a chord, ringing strong and true through my very psyche. It brought the pain of gun violence in this country to my front steps by shooting the film in the community where I grew up.

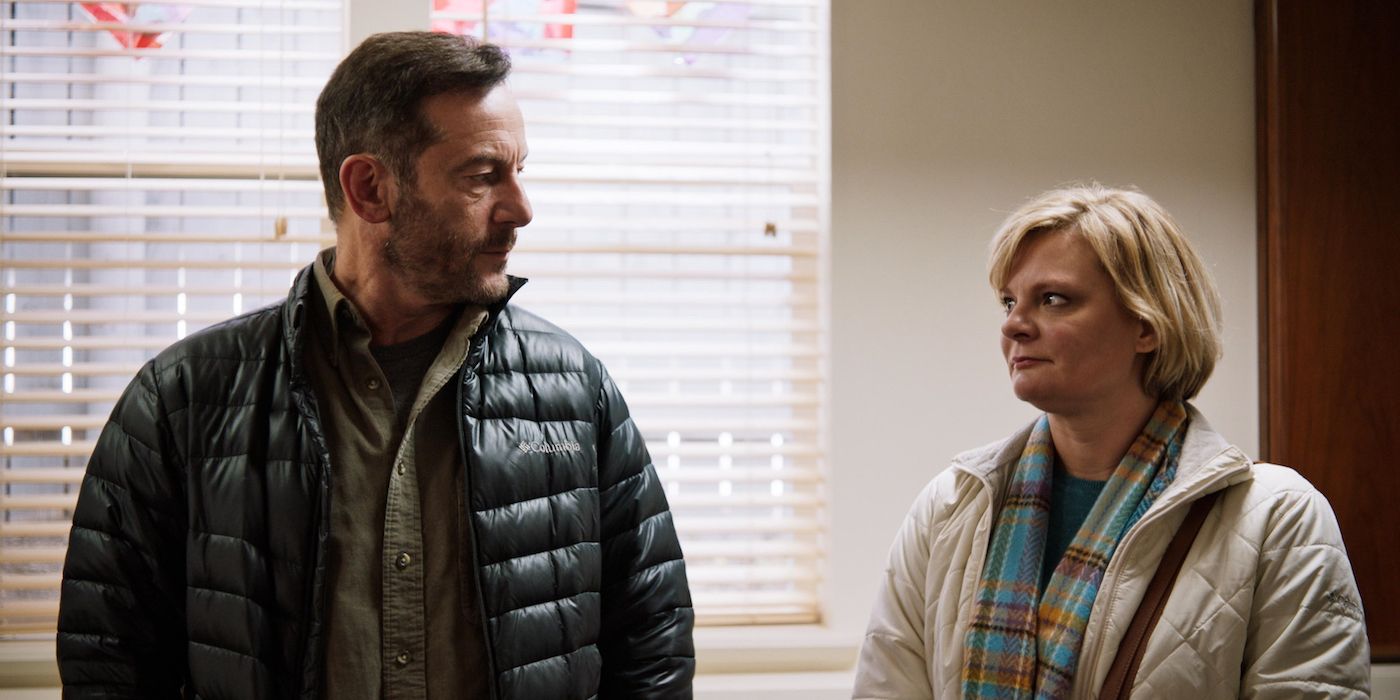

The film is set almost entirely in a single church with four characters, two sets of parents, sitting around a table and discussing a mass shooting that tore apart their lives. Jay (Jason Isaacs) and Gail (Martha Plimpton) are the ones who lost their child. Richard (Reed Birney) and Linda (Ann Dowd) are the ones whose child took the lives of many others. All of the cast is outstanding, a masterclass of character actors giving their all to characters working through unimaginable suffering. The impact their performances left on me was all the more significant because of how close to home it all was.

This closeness is both literal and thematic. The literal sense is that the building where the long conversation takes place is the Emmanuel Episcopal Church in Hailey, Idaho. It is right up the street from what used to be the sole grocery store in the small town, with a population of under 9,000 people, and no more than 10 minutes from where I went to high school. Upon first seeing the film, I immediately recognized the location. I had heard some inkling that the film had been shot in the Wood River Valley where I grew up, though I hadn't expected it to so clearly be set in locations that hold such a vivid place in my memory. Having since moved away to Tacoma, a city just outside Seattle, I am used to the cinematic deception of only pretending to set a film in a place when it actually is shot elsewhere.

That was not the case here. As Kranz told my hometown paper, the place was important as he “wanted to achieve a real sense of America, especially in the landscape, even though most of the movie takes place in one room.” The film does that with a quiet subtlety, providing frequent breaks in the narrative by cutting to a quiet, empty field near the mouth of Quigley Canyon that has a glimpse of the football field next to my high school. It serves as a respite from the trauma, for both the characters and the audience, that was all too familiar to me.

More than a decade ago, I too had found myself in the fields, seeking just as the characters do to hide from the horrors of the loss they are facing. There were people I knew and grew up with who did not leave the valley as I did, their lives brought to an abrupt end by a gun. It has only continued, with every time I come back home seeming to bring new stories of loss. Deaths fill the newspaper, a more honest portrait of small-town America that is simple and largely unacknowledged despite how widespread it is. The brilliance with which Mass captures this more unflinchingly than any other film has before it is gut-wrenching.

This past week, I went back home and went to all these places to remember. The streets are now immortalized on film and in my memory in equal measure. I went to the church where the film was shot. The kind staff let me walk around to see the various locations where the story played out. I took in everything I could, from the small room where the bulk of the film is set to the pews upstairs where music pours downstairs, providing some degree of solace after the film's darkest moments. I got to meet an adorable dog named Rosie, who bears a striking resemblance to Toto from The Wizard of Oz. I saw news clippings of coverage of the film stapled to a bulletin board no more than a couple of feet from where the film was shot. It was already a surreal experience made more so as the church prepared for the holidays, overflowing with joy. It served as a stark juxtaposition to the tragedy of the film.

While working on this piece, the reminders of just how dire things are kept crashing in. When away from where I now live in Tacoma, my former colleagues reported there was a shooting at the mall on Black Friday. You probably don’t know about it as it had fewer victims than another shooting that same day that left three shot and three wounded at a mall in North Carolina. As I was putting the final touches on this piece, there was a school shooting in Michigan that left four dead and seven seriously wounded.

Even as 2020 saw mass shootings briefly decrease due to nationwide lockdown efforts, the year was the deadliest for gun violence in decades. These incidents have become depressingly commonplace in communities across America, a problem endemic to the country that is not seen on such a scale anywhere else. The sheer number of guns and their capacity to be used for violence is increasingly thrusting us into an uncertain world where shootings can only become even more commonplace.

It is in such a dire world where Mass finds itself and where, despite how bleak our reality looks, I found a more genuine grappling with the violence that permeates so much of our everyday lives. The profoundly painful conversation on display in Kranz’s film is one that isn’t seen in many other works, and it is understandable why. It can be hard to confront the looming reality of mass death that underlies the film. Yet to not do so, especially when the carnage is so prevalent in American life, would be to lie to ourselves about what it is that we are facing. It is a deception we perform on ourselves as we do what we can to provide a shield against the horrors of our world. We try to preserve ourselves to find a way forward.

Kranz captures that desire to find a path toward truth and healing. The characters go from being people who dance around the reason they are there, masking their trepidation with politeness, to getting it all out in the open. As Kranz told Collider in the lead-up to the film’s release, he himself had to confront the reality of now being a parent where his child was growing up in a country where such violence could happen. He was operating in the wake of the Parkland shooting and strived to find something resembling restorative justice. To hear Kranz talk about it, it is hard not to be taken in by the prospect of healing the divide through such a conversation and finding a way out of it.

The type of reconciliation seen in Mass is cathartic in how unique it is. There has been nothing quite like it amongst any of the films released in this or any year. It found particular significance for me by being in my hometown, though it finds a deeper resonance because of how it taps into a growing violence we all have to reckon with. It is transcendent precisely because of how this story not only could happen anywhere in America, but does, in fact, happen everywhere in America. The conversation is a microcosm of the pain that has and will continue to wreak havoc in communities across the country. It provides some glimpse of the healing that is possible, though it remains wrapped in a heavy burden.

Despite this, there has been a tendency of some to view the ending as too neat. Having seen it now multiple times, it has become clear to me that the characters are striving for such a resolution and even shift back into the normal patterns of politeness in order to expedite it. However, the final scene where Dowd’s Linda walks back into the church and offers a final story complicates this. She recounts to Jay and Gail something she hasn’t told anyone before, becoming vulnerable in her honesty about the events that led up to the shooting. It is honest and painful as it shows there is still much that needs to be done on the path to healing. As she gives life to one final scene in the church of my community, Dowd provides the most genuine and open portrayal of how broken we remain.

The messy reality the film grapples with will always be there, both for the fictional people that populate it and we that watch it. I will likely still go home and hear of more loss. That harsh truth has been made into an inevitable tragedy of life in our communities, a product of so many factors and failings that leave us with little room to see a path out. Yet Kranz shows a small glimpse of what true healing can look like amidst all the pain. Even when dealing with the utter and complete destruction of our lives, not all is forever lost. It will never be easy, but Mass showed me that there is a place where peace can be found in the field. As the final frames of the film take us back there one final time, with the lights of my old high school football stadium illuminated in the distance, Kranz is able to carve out a tentative tranquility amidst the chaos.