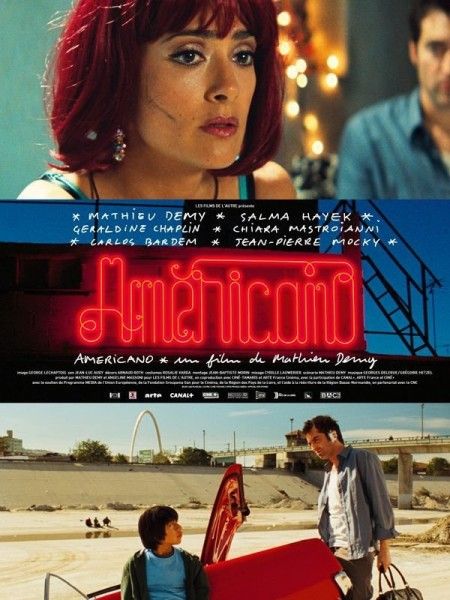

Written, directed and produced by Mathieu Demy in his feature directorial debut, Americano deftly mines the past of a true-life filmmaking family, while at the same time weaving a mesmerizing fictional narrative about coming to terms with unexpected grief and uncomfortable pasts. The stellar cast in this moving drama about inheritance and legacy includes Salma Hayek and, perhaps not incidentally, the children of famous film personalities – Geraldine Chaplin, Chiara Mastroianni and Demy himself.

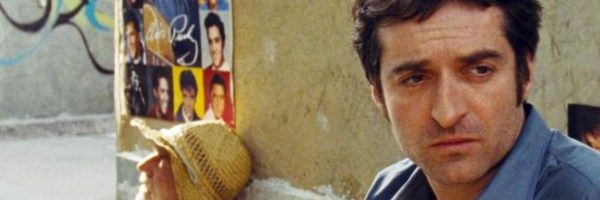

We sat down with Demy at a roundtable interview to talk about Americano which functions both as an homage to his famous parents, filmmakers Agnes Varda and Jacques Demy, and as a work that stands entirely on its own. He told us about the challenges of directing a low budget international production shot in France, Mexico and the U.S., how he chose to shoot his first feature on film rather than digitally, and why he decided to integrate footage from his mother’s 1981 feature Documenteur into his film. He also discussed how he intended Americano to be a road movie about grief and the mother-child relationship and was inspired by filmmakers like Claude Miller, Wim Wenders and Atom Egoyan. Hit the jump for the interview.

Question: What inspired you to integrate into Americano some of the footage from the film your mother made back in the 80s?

MATHEIU DEMY: It’s a feature that’s one hour long called Documenteur which is a play on words between ‘documentaire,’ which is ‘documentary,’ and ‘menteur,’ which is ‘liar.’ It’s a very personal fictional film that she directed in which I was acting as a child. I was trying to make my film more personal by using this footage. I had the ambition to do this road movie about grief which is more or less a universal story about a man losing his mother and the relationship between mothers and children. I wanted to make it more personal because it’s the kind of cinema that I relate to more. This is when I decided to act in it and use that footage and try to make it more personal.

Did you reverse the mother/father relationship in this fictional story and was it inspired by your own background?

DEMY: I did lose my father a long time ago. Yes, I definitely wanted to talk about that, but in a fictionalized way. There’s lots of both in there. What I felt was interesting was to say that the grief process is something very unexpected. In the film, the character of my father says “Okay, you’re going to go back to Los Angeles. You’re going to bring back the body, sell the apartment, and then it’s done.” But you can’t really do it that way. You have to live your own experience and it’s very different for every person. You have to live through that. This is what I wanted to express – that he had to do it his way. He screws everything up, but ultimately he’s going to find a way to be at peace with the memory of his mother and try to understand better what his background is. It’s a little bit about talking about things that were personal to me in a fictionalized way.

I see you have a tattoo of “Americano” on your right arm. Did the tattoo come first or the film?

DEMY: The film came first, then the tattoo came during the film.

Was that inspired by your commitment to the film?

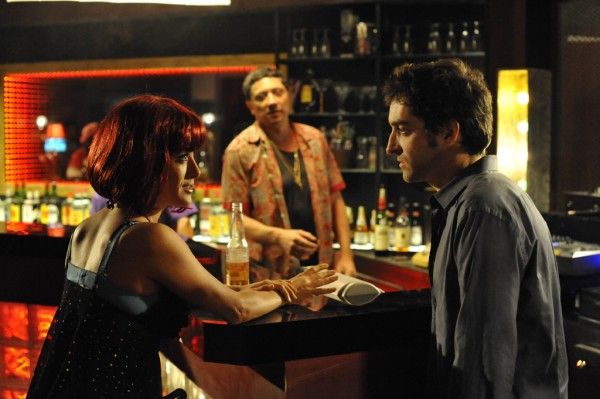

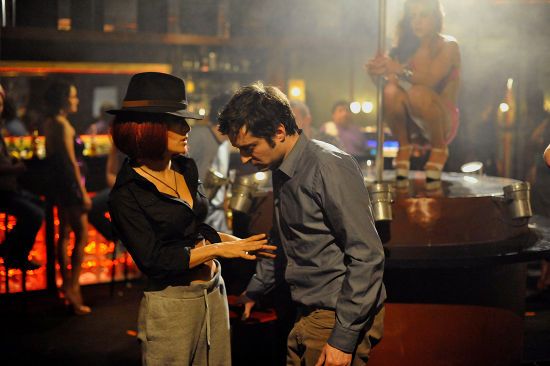

DEMY: He faints at the beginning and it becomes the title. I figured out that it was a way to tell that he was going to sink into himself to find the solution, because this is the logo of the bar, this slightly imaginary place where he finds everything out. Everything comes together in that place. It’s like the l’oeil du cyclone (eye of the hurricane) or centerpoint of the film. It was also a way to say that we were entering an intimate tale because the film is not very realistic. It’s not that kind of film.

Can you talk about the cast you assembled that includes Salma Hayek and also Geraldine Chaplin and Chiara Mastroianni who are children of famous film personalities?

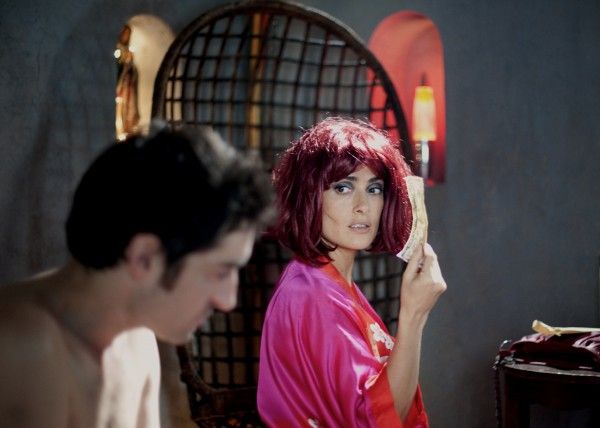

DEMY: Well that was on the top of that. I didn’t cast them for that, obviously. I tried to work with people that I really admired. I had written the part for Salma because I’m in love with her and I think she’s fascinating. I’m totally in love with the way she acts and I think she’s a great, great actress. I also wanted these three women because it’s mainly these three countries and three women to reflect the journey that he’s having. This is the story of a man who’s running away from something and going far away from home and far away from his references. I thought the Chiara Mastroianni character was a wonderful beginning to that because we have a lot of history in common — her mother and my dad. Chiara Mastroianni is the girlfriend and she happens to be the daughter of Catherine Deneuve who was my dad’s iconic actress. We’ve grown together and she’s exactly that same age as me. I think we have a lot in common and I feel very close to her. She also embodies what really is French art house cinema today. It was like a starting point that’s really interesting and she’s a great actress. And then, Geraldine, by her culture and her filmography, makes the link between the United States and Europe. Also, she had this great humor and I wanted a comedic character to weep and be so [emotional]. She had this great sense of humor that could allow this and bring me a little bit further from the roots. And then, Salma is about the last person you would expect in a French film that’s independent and broke. I thought it was really interesting that she took the film even somewhere else. In a way, those three women had to bring this Martin character through his journey. This is more how I tried to imagine the cast. On top of that, it’s a film that I think talks about family issues and also talks about cinema because it’s the sequel of that 1980 film of my mother. I figured out it would be fun if the actresses could also have that kind of cinema history.

As a storyteller, do you feel you lose something when you’re not shooting on film?

DEMY: It’s pointless to go against digital because sooner or later you won’t be able to do anything else. Every film also has its right format. I thought that for this film, working with the footage, I wanted them both to be organically the same but the time difference would show something. So, I used Super 16 Cinemascope. It’s very different from simple 16 of 1981, but we still have the same feel. This is why I chose film. I have a tendency to think that film is still more interesting today, but sooner or later digital is going to take over.

Next year, in 2013, at least a thousand theaters across the country will be closing because they don’t have the money to convert.

DEMY: That is sad. It is very sad. Well, digital projection, that’s for sure. In France, it is almost 80 percent now the case. But it’s about recording the images. In music, we can still record analog and then do the post production in digital. In film, sooner or later, we’re not even going to be able to film because they won’t be able to process. The labs won’t exist anymore, pretty soon. You’ll just have to do it with digital.

Do the French have a preconceived idea about Tijuana? We know about Tijuana and we don’t go there.

DEMY: (laughs) Yeah, that’s a preconceived idea. Instead, I would say I’m going to shoot in Tijuana. But an American person would say “Oh it’s really dangerous.” “Have you been there?” “No.” “Okay, so?” I had the best time in Tijuana. It was perfectly safe and perfectly cool and incredibly inspiring and easy to shoot. I was with the right people and I felt safer than in some areas of Paris. I thought the people were nice and they looked cool, were patient, looked amazing, and the light was fabulous and the colors were nice. It was great to shoot in Tijuana. We shot there for two weeks. What I love about Tijuana, and Mexico in general, is that it’s one of these countries where you still feel that you can discover some things. You still feel that you can walk in some place – like a bar or a home or a hotel – and find it really funky and cool, and you want to film this, and you can still get away with that. I go see the owner and say “Can we do that?” and he says “Yeah, sure,” and I say “Can you be in my film? You look cool.” “Yeah, sure. Why not?” It can actually happen and not cost a ton. I like that way of interacting between reality and film. I think it’s really interesting. You can do that in the States, but in L.A. it’s not like that. It’s harder because it’s a more studio-based industry. It’s the city of the studio. Even in Paris, it’s difficult to shoot that way. But you can shoot that way in Mexico. There are lots of places in the world where you can still discover stuff and I think it’s interesting for small films, for very small independent films. Then, when we arrived in Los Angeles, it was suddenly a little more complicated and a little more expensive and a little more professional, which is not easy for that kind of budget. That was sort of a change.

Was it challenging to direct an international production like this where you’re filming in three different countries?

DEMY: No, no, that was nice. We were maybe nine people from France – the D.P., my first A.D., and the person who built the sets. The major creative persons around me were my French friends that I’m used to working with. They’re my crew. Then, we traveled and tried to add to this some [additional] crew members here in Los Angeles and in Mexico. We had a Mexican crew over there and an American crew here and a French crew there with a common route, and that was fun.

There’s a tonal shift between what you shot in France, L.A. and Mexico, and each segment is distinctly different. How did you approach the visual style of the film?

DEMY: It was a deliberate choice to try to match, as we were talking about the casting, the way these three women should take him away from home. I was willing to express through the images and the style that this guy was going to be more and more involved in his own memories, more and more emotional, and more shook up by what’s happening to him. He starts off rejecting all of his memories and rejecting what is happening to him, in denial of all that. I figured out it’s pretty gray and blue and cold and wide. When we arrive in L.A., there are more traveling shots and it’s warmer and yellow and a little closer. And, as much as he gets agitated with his souvenirs and obsessed with the Lola character, then Mexico is really shoulder shot, really close-ups and really red. So these three [are distinctly different] because the character changes. He totally changes. I wanted everything to go that way to bring him to that kind of change. This was the deliberate choice for the style of the film. For that matter, too, we didn’t really shoot anything other than him or subjective shots of him in order to try and portray this man, because it’s that kind of film that portrays him and his feelings and the way he changes.

Growing up in film, was cinema the biggest thing in your life? Was that passion always there for you or were there years when you were not into it as much?

DEMY: Yes. I had my little teenage craziness where I wanted to be a doctor, I admit. I have to confess at one point I considered even going to school. Hopefully, I went back on the right track being an artist. No, I’m just kidding. It’s obvious when you grow up. For me, my parents, and especially my mother, always made films in a very artisanal kind of way. Her office was at home. She was always filming low budget stuff and including her family inside. It was more a way of life. I related to that from the beginning. As all of those professions of artisan, it often skips the generations, like shoemakers or boulangers – the people who make the bread – or when you grow up in a garage and you want to maybe take over the garage. I feel like it’s more like all those professions. And then, at one point, I wanted to do something else as a teenager and I rejected the family thing. It was like no, I don’t want to be an artist. But, finally, I’m not really capable of doing anything else. I enjoy very much filmmaking so I came back to that.

There’s a beautiful shot of a car skimming across the water at low tide that’s evocative of films from the Nouvelle Vague era. What inspired that?

DEMY: It’s a place where I grew up a little bit also. It’s called Noirmoutier and it’s a little island near Brittany in France. There’s this road that you can only access when the tide is low. It was pretty intense because we waited until the last moment to say “Action!” and they were freaking out in the car. It’s not an explicit reference to anything I can think of on a conscious level anyway. Like I said, I definitely tried to make some shots that would be long enough or strange enough to try to make you think of something else and eventually some other cinema references.

Can you talk about the fate of the red mustang?

DEMY: Like a lot of things in this film, I wanted to use some strong images of what the American fantasy could be also for a French filmmaker and try to use some iconic images that would trigger your imagination to think about other films, and also because it’s the pace of that kind of story where you follow a character and you have a little time to escape and dream. The film is full of references. That footage is a reference to the work of my mother and the Lola character is like a memory of Jacques Demy’s first feature, Lola. The film is full of little references that I wanted. That Mustang is very iconic and I wanted that also to be part of the process. I don’t know how much the Mustang is worth and I don’t care. It’s just like that – he abandons the car. I thought it was fun. There’s a lot of stuff going on. It’s the Rio Tijuana. There’s a lot of stuff in there. I figured this could be a possible ending for the mustang.

Were there other films besides your parents’ films about losing someone or grief or exploring emotions that were in the back of your mind when you made this?

DEMY: Oh yeah, definitely. There’s a French film called Mortelle Randonnée (Deadly Circuit, 1983) by Claude Miller who just passed away two weeks ago. He was a great director. This film is with Isabelle Adjani and Michel Serrault. It’s a beautiful film about this detective on the trail of a serial killer, the woman played by Adjani. She plays all these different characters and she’s crazy and beautiful. He lost his daughter and he fantasized that she could be his daughter and he’s after her. It’s an extraordinary film. It’s both a thriller and very psychological and a little magical at times and it’s funny, too. It’s very unique. I had this in mind. I had Paris, Texas [by Wim Wenders] in mind which is about losing yourself and finding yourself. It’s also about the mother-child relationship and the strength of that bond. I had Exotica in mind by Atom Egoyan. I really liked the relationship between this guy who comes to see the stripper, the schoolgirl. What I loved about it is that you think he’s some kind of perv, but ultimately you discover that he’s just trying to relate to the babysitter of his dead daughter. He’s not here for that. And, in a way, this is also the story of Martin, how he comes to this place and he wants to talk to Lola and wants to spend some time with her. He’s not here for that. He can’t even manage to screw her, which is not very believable.

There’s a lot of anger when he’s throwing his mother’s possessions out. Is it interesting to go into that level of emotion?

DEMY: It’s not only about anger. It’s also about not being able to face the choice of what should stay and what should leave. It’s a crazy dilemma. Do you want to keep everything? Should I just keep the pictures? What’s the rule? And, if you’re mad, you might as well throw everything out. I can understand that in a way it’s different from anger. It’s just that it’s too much to make a choice, to avoid making a choice.

One of the things I loved about the Nouvelle Vague is, not only were they great filmmakers and storytellers, but they were passionate cinephiles as well. Do you see that kind of filmmaking spirit still alive today?

DEMY: Yes, definitely. I try to work a little bit like that and be very passionate about it. Maybe this film can also relate to the Nouvelle Vague in the way that the production project is pretty crazy — with little money, shooting in three countries, and shooting in film versus digital, and rebuilding the whole Americano in Paris because it’s a set. These are artistic decisions that are not cheap, so that production project is really crazy, and the New Wave was also about allowing really wild production choices. It’s as much the producers that did the New Wave as the writers. The producers had to go with that – that freedom of work. In that way, this is sort of that kind of spirit maybe, except the French New Wave is over, even if in French cinema nowadays there are still a lot of references. You can feel that it is in our background, but there’s not a new New Wave of anything. That’s the strange thing about cinema nowadays. I don’t think we really know where it’s going or what group there is of influences to lead some project. There was the Dogma thing with that kind of stuff that was really interesting, and now I don’t really know where it’s going. 3D? I don’t think so.

When I attended the French film festival here in Los Angeles, it struck me that the French really make most of their movies for themselves.

DEMY: I don’t think so. I don’t really share that. I think there’s a lot of American movies that influence French directors. It depends. One of the things I’ve noticed during this week of French cinema is the diversity. When we were all on stage, the people made so many different films – very, very different films. It’s one of the strengths of the system we have. Each time you sell a ticket, even in American movies, part of that money goes into funding for French cinema. It’s the audience and the American movies who finance French cinema which is a cool way of making a closed circuit. This is why French cinema is strong versus other European cinemas that have the tendency to disappear. Italian cinema was in the ‘60s, and what it is now is sort of sad because it’s too expensive and too complicated. The strength of French cinema today is to have this diversity, and in this diversity, there are also some filmmakers who are very oriented towards an American way of making films, in my opinion.

With Documenteur, there is the gradual expansion of the 16mm frame to ultimately that final shot. Can you talk about how that idea progressed for you?

DEMY: This is when I chose the format of Super 16. We tried everything. We tried small camera, the big digital and 35. I didn’t want to have any kind of preconceived idea. It was just what would work for that. Super 16 was the same organic thing, but it had changed a lot. The stock from the 80s and the Super 16 Cinemascope are very different in quality. I thought it was the perfect thing. I wanted to use Documenteur as unrestored, as if I’d found it in a box like a document. We had to scan it in order to include it in the modern film. We scanned it before it was repaired, as the negative was. I thought it was cool that we would use it in the format of that story. It would help make it understandable that it is a memory and that it is also a film. For some people, it would give a clue that it might be another film. It was part of those little details that I thought it could make people wonder why and maybe get curious about the background story. I really tried to make a film that has a pretty universal theme – the death of the mother, grief, and the road movie. I tried to make that as universal and understandable as possible without the references. I guess you don’t need those references to the cinema of my parents or anything to understand the film in a way. But, I also wanted people to have little hints and ask themselves maybe why is this or why is that. This is also why I had this format kept the way it is.

Someone mentioned the other day that digital can capture the warmth and the grain of film stock. Do you see that happening or will digital never be able to do that?

DEMY: Sure. Of course. You can make digital look like film, but it’s still not the same. Film is processed. The way you process digital to make it look like film is not the same work. I mean, it’s not the same implication. For the moment, I’d prefer to get used to digital, get used to that image, because ultimately we’re going to have to do that anyway. Just get used to that image and try not to make it look like film which is a little bit like fake leather. I like real plastic better than fake leather. So, let’s have real plastic and be happy about it and not try to do something else. But it’s true that digital is another way of thinking, and when digital is going to be the only way to go, then we’re going to be comfortable in that way, too. We’re going to be comfortable that digital is like a negative, and then you can do whatever you want with it. You can make it look like this or like that, or grainier or less. Little by little, I think it’s going to replace film. Maybe in five or ten years we’ll be able to look at it as if it’s the standard aesthetic for film with no problem at all. It’s just that we’re in the middle of things now. We have to slowly grow into it. This is the way I feel because there are a lot of filmmakers and cinematographers who are already totally in digital and say there’s no use to go with the past. As a first time filmmaker, I thought it was interesting to do it in film, and whenever it’s still possible, I still think it’s interesting to shoot in film because soon enough it won’t be possible. That’s why. But I certainly don’t have any nostalgia about that. You just have to follow the way the world goes, too. You can’t be an old prick when you’re not even 40.

What did you take from the process of making this film as both your feature directorial debut and something that’s also very personal?

DEMY: It was great fun. First of all, I really had a blast. It was terrific. What I felt was an adult way, a more mature way of thinking cinema. When you’re an actor, you’re very much exposed, but in a strange way you’re totally protected behind a character, behind a script, behind a director. Being the director is really something. It’s a statement of something and you have to stand up for that. Okay, this is what I see. This is how I see the world. This is how I see cinema. And you have to be able to talk about that and explain it and be responsible. So I thought I might finally be growing up.

Americano opens in theaters in New York on June 15th with a national roll out to follow.