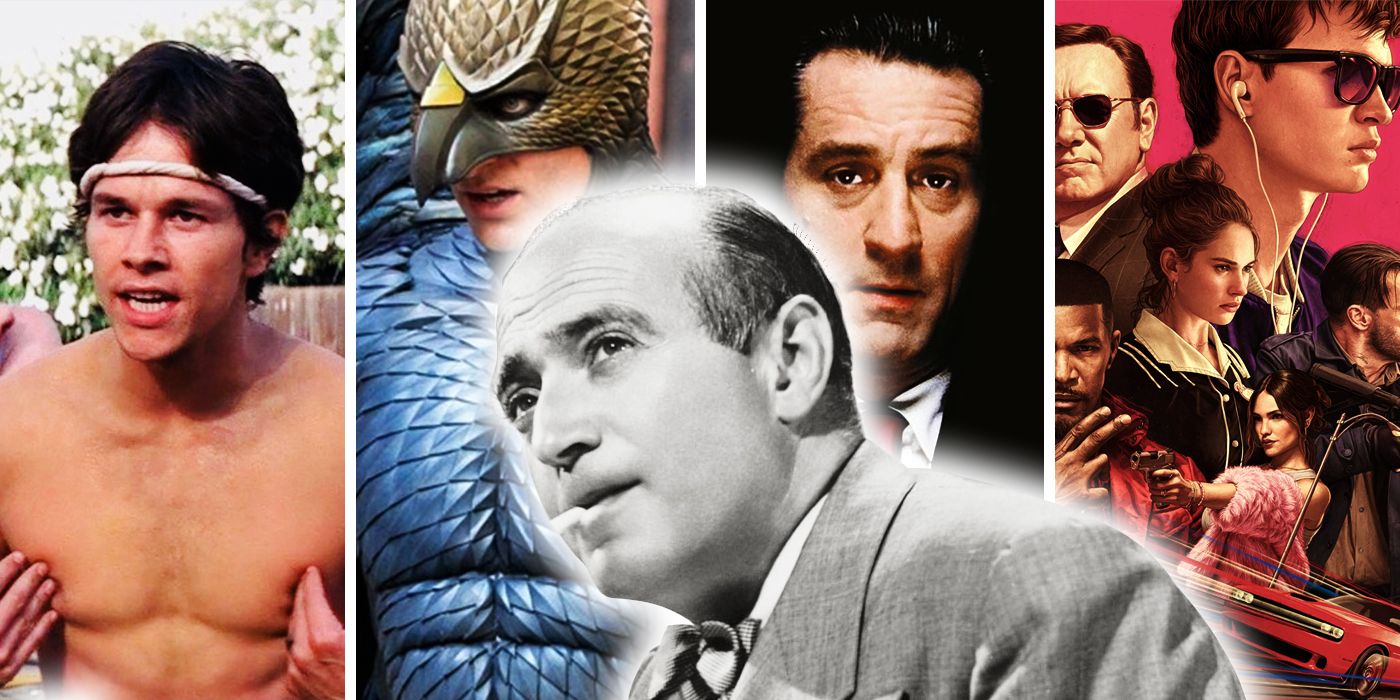

An elaborately choreographed and perfectly executed long take is pure catnip for many filmmakers and cinephiles out there. Seeing the camera glide along for minutes on end, whether it be following Henry and Karen Hill (Ray Liotta and Lorraine Bracco) through the back halls and kitchen of the Copacabana nightclub in Goodfellas. Or tracking a car as it crosses the border between the United States and Mexico with a bomb in the trunk in Touch of Evil, it gives the audience the simultaneous thrills of pulling us along in the story and wondering how in the world they even achieved that shot. With the prevalence of digital cameras and computer automated equipment, these tracking shots and long takes have become even more elaborate, often to the point of filmmakers doing them just for the sake of it, regardless if they are effective for the moment or not. Even whole films are shot entirely in one take, such as Sebastian Schipper’s 2015 film Victoria, or made to look as if they are one take through digital trickery, like Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s Best Picture winner Birdman.

The best of these complicated shots are the ones that plant you directly in the shoes of a particular character on screen, letting you go through the world of the film and experiencing it just as that character is. No director has been better at capturing this feeling than German auteur Max Ophüls, who turned using dollies and cranes into a true art form in his films until his death in 1957. Ophüls manages to gracefully maneuver the bulky cameras of the time down streets, through entire homes, and up and down staircases with what looks to be total ease. Every movement made by the camera is dictated by the character on screen’s actions. The precise clarity of the camera’s movement added with the intense subjectivity lent to that movement have been elements implemented by filmmakers ever since, from Paul Thomas Anderson to Edgar Wright.

To perfectly illustrate Ophüls’ subjective gaze, let’s look at the opening shot from his 1953 film The Earring of Madame de…, arguably his finest film. The shot, lasting two and half minutes, follows the titular Madame (Danielle Darrieux, a frequent collaborator in Ophüls’ final stretch of films), an elegant society woman of Paris, looking through her many jewels, furs, and other accoutrements in order to find an item she is willing to sell in order to payoff her substantial debts accumulated from her lavish lifestyle. Beginning as a closeup of her hand, the camera lets that hand determine its speed and movement, as it opens jewelry boxes, opens closet doors, runs along fur coats, and accidentally knocks over a bible. It is not until the camera moves to her dressing table that we see her face for the first time, as she tries on a hat in the mirror. While not directly being a first-person point of view, the focus of the frame remains on what she experiences in the moment. When she eventually gets up to walk out of the room, the camera moves right alongside her.

Where most films have a few, or perhaps even just one, of these long takes, The Earrings of Madame de… and the rest of Max Ophüls’ work nearly have them in every scene. By the time he was making Hollywood films in the 1940s, such as the heartbreaking masterpiece Letter from an Unknown Woman, this style essentially became how Ophüls knew how to tell a story. Actor James Mason collaborated with Ophüls on his two 1949 film noirs Caught and The Reckless Moment and composed a poem to describe how these shots were so important to Ophüls:

“A shot that does not call for tracks

Is agony for poor old Max,

Who, separated from his dolly,

Is wrapped in deepest melancholy.

Once, when they took away his crane,

I thought he’d never smile again.”

A lot of filmmakers need to find an excuse to execute a complicated tracking shot. For Ophüls, it was simply how he saw cinema, where his actors and camera moved as one. His films, which draw on the style of interior, romantic storytelling (romantic in the literary sense), require that immediacy and consistent point of view in order to be successful. Had that opening shot not been a long take but a scene filled with shot reverse shot cuts of the Madame looking at her belongings would have completely disturbed the flow of the stream of consciousness search, making every move feel deliberate.

The aforementioned Copacabana scene in Goodfellas, while using a Steadicam that had not been invented in Ophüls’ day, draws directly from the same ethos of experiencing what the characters are firsthand. When they see something new, we see it at the same time. When they turn a corner, we turn that corner with them. The bravura opening shot of Boogie Nights from Paul Thomas Anderson, which directly echoes Goodfellas by it following people into a nightclub, ramps up the Ophülsian subjectivity by changing character points of view within the same shot. Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver features a number of sequences in this vein, most notably the titular character’s first coffee run, completely choreographed to “Harlem Shuffle” by Bob & Earl. Even in the smaller moments of Wright’s films, such as a character grabbing something or looking to something initial off screen, the flow of the camera abides by how Ophüls operates, even if it isn’t a part of a several minute long single take.

Plenty of filmmakers attempt this kind of tracking shot but find themselves not entirely committing to the point of view. The long takes in Alfonso Cuarón’s dystopian thriller Children of Men, while enormously effective on their own, dip in and out of strictly following that singular point of view depending on what would most effectively create the most tension in a given moment. The long tracking shot set on the beach at Dunkirk in Joe Wright’s Atonement begins in the point of view of Robbie Turner (James McAvoy) taking in his surroundings on that chaotic beach but eventually morphs into an overall picture of Dunkirk, where the camera goes where it wants. Then there are the action films utilizing this technique, technically, but often feel more like the filmmaker wanting you to be impressed that this big action set piece was done in one take rather than be invested in what is happening, such as Atomic Blonde or Extraction.

Even Max Ophüls most absurd, show off tracking shot, the five minute opening shot of La Ronde, following the film’s Master of Ceremonies (Anton Walbrook) explaining the thesis of the film while walking through a film set, changing costumes, coming upon a carousel, and revealing Simone Signoret as it spins. The camera never stops focusing entirely on Walbrook and his experience in the moment. Film critic Andrew Sarris wrote of Ophüls’ signature technique, “Montage tends to suspend time in the limbo of abstract images, but the moving camera records inexorably the passage of time, moment by moment.” The films of Max Ophüls deal entirely with the emotional state of the character at that moment and how their current actions affect that state, and while these elaborate long takes and tracking shots can certainly be admired for their intricacies on their own, their true beauty comes from the storytelling power they possess. Plenty of filmmakers try to emulate Max Ophüls’ camera movement techniques, but few come close to really understanding why he implements them in the first place.