When Neon announced that the release of one of the year’s most anticipated arthouse films, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria, would be limited to a never-to-be-streamed theater exclusive in which only a single theater would be screening the movie at a time, it initially seemed kind of fitting. The work of few filmmakers besides Weerasethakul’s could make a convincing argument for such an orthodox release strategy.

Like the recent filmography of Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-Liang, so devoid are his films of traditional plot and structure that they more closely resemble a feature-length art piece than the conventional idea of a film. But as “artful” as these films are—and Memoria is as much so as any other in his catalog—what will this elusive release plan mean for moviegoers around the country? Can Memoria’s unique one-theater-only existence add to the distinctive ambiance that the film creates, or is its near-unavailability too high a cost to warrant it?

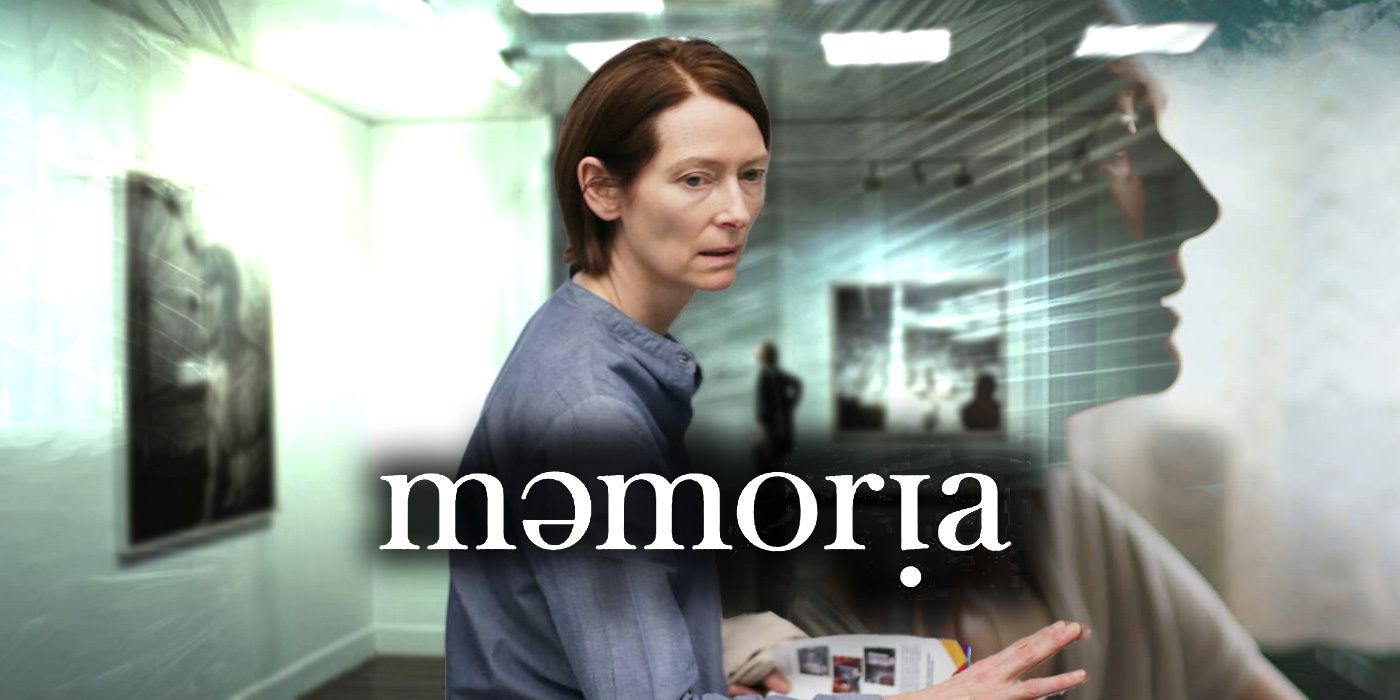

There's a noise in the middle of the night. It is loud and unidentifiable. For the next two hours, it will recur time and time again. It always sounds the same, but it never becomes more easily describable. Jessica (Tilda Swinton) seems to be the only person who can hear it. Is it only for her, and can it even be explained? Such is the premise of Memoria, a film that uses sound production unlike any other.

Weerasethakul’s first work not to be in his native Thai language, Memoria creates a sensory experience that uses its sounds to immerse the audience into the reality of the movie. What Jessica’s enigmatic noise sounds like is crucial, for the intention is not for the audience to know that she hears it, but to share the experience of hearing it with her. When the film occasionally succumbs to silence, the absence of sound is equally important to the sound itself. Not hearing is as important as hearing. Sound pollution or other aural distractions, more likely in a home-viewed setting, lessen the impact of the silence.

Memoria’s one-of-a-kind transcendental experience benefits heavily from the theater experience, and some may argue that’s reason enough to keep it there. Giving significant importance to a theatrical release is by no means an uncommon practice for movie studios, especially as of late. Neon’s release of Memoria simply takes this practice and exaggerates it to an entirely new level. In the past couple of years, in order to ensure that moviegoers were still physically going out to cinemas, many high-profile films have had their release dates delayed in reaction to cinemas’ extended closures.

Instead of becoming available to stream, movies were pushed back indefinitely to wait for cinemas to open again. While partially a financial decision, keeping films at least initially in the theater also occasionally came at the request of the films’ directors. In the wake of closures, Christopher Nolan, a champion of movie theaters everywhere, wrote a heartfelt ode to cinemas and those who run them. Seeing a movie in a theater, sitting amongst strangers with the benefit of large screens and immersive sound equipment, is undeniably a different experience from watching the same film at home.

True, Tenet is a larger-than-life spectacle that did benefit from the theater experience, but since the movie’s digital release there’s now nothing stopping anybody from watching the movie on, say, a cellphone. So if delayed movies like Tenet and No Time To Die eventually made their way onto streaming platforms, why won’t Memoria?

The antithesis of the theater-favoring release can be found in the Warner Brothers and HBO Max partnership, in which new releases premiered in cinemas and on the latter’s streaming platform on the same day. Moviegoers were given the choice of what viewing method suited their preference — or needs — better. Memoria is as immersive a film as Tenet, The Matrix Resurrections—or any other extravagant blockbuster.

While a picture like Tenet is not without its artistic merits, it also exists, to a large degree, to entertain. Even with its trademark philosophies on time and fate, it also retains its status as a high-profile action flick. Memoria, as with the rest of the director’s movies, is different. Something like Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, Weerasethakul’s Palme d’or winning drama, would be a harder sell than the star-studded The Suicide Squad, which was available to stream on HBO Max on release day. Considering that Memoria adheres to the director’s trademark cryptic style, it too can make for a hard sell in wider audiences. Weerasethakul seems less concerned with traditional entertainment than he is with creating something singular, a vast and grandiose artistic statement that audiences experience, which is definitely fair, until too few are allowed to join.

Beyond his career as a filmmaker, Weerasethakul has established himself as an artist in other mediums. In 2021, he had a featured exhibit at the Institut d'art contemporain de Villeurbanne in France. The exhibit, titled “Periphery of the Night”, featured a series of dark rooms in which projected videos create a multimedia experience meant to “[enable] us to experience new cadences and [transform] us”. Stills of the exhibit on the museum’s website show obscure images not unlike what's found in Weerasethakul's feature films. Beyond availability, is there even a clear distinction between the filmmaker’s art exhibit and his more widely-available feature films?

In 2019, Hip-hop artist Yasiin Bey released his latest album Negus in perhaps the most novel method possible: as a two-month-long “listening art installation” at Brooklyn Museum. It was an album that essentially lived and died there, with no digital or analog release of the album planned to occur. Ever. Opponents to the release considered it to be not only bad for fans but also for the genre. Those fortunate enough to get the opportunity to visit the exhibit, to hear the album was surely a once-in-a-lifetime experience, but for those unable to attend during its short-lived lifespan—for financial, locational, or any other number of reasons—it may as well have not been released at all.

The argument of Memoria's artistry warranting its unavailability is faulty. One could compare it to Weerasethakul's art exhibit in France, but its subjective status as art doesn't make its being exclusive any better. It’s true that art exhibits also stick to cities and rarely make appearances in lesser-populated areas, but in the current era, a vast majority of crucial artworks have been digitized and are thus accessible to anybody with a computer. One doesn’t need to visit the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa. One can simply visit Google. With Memoria, one has to be present at a given location, in a given moment. It's a concept that works better in theory than in practice. Though Neon suggests that the film is meant to continue its multi-locational tour indefinitely, the question of when, if ever, it will be screened in a given location has no certain answer. Even for those willing and able to travel to see the picture, there's no guarantee it will screen at an accessible theater. As of January, only two theaters in the US have shown the movie—New York and Chicago, each for one week.

The international release of the film is being handled by different distribution companies, none of which have announced having the same intentions of a deliberately withheld release. With distributor and streaming service MUBI owning the film in several other international markets, it seems unlikely that the film will be offered in a similarly exclusive release. A wider, more accessible release abroad, while arguably beneficial to moviegoers who reside there, would not make the film any easier to see in the US.

If and when a digital and/or Blu-ray release occurs overseas, North Americans will still be exempt from being allowed to view the film at home, due to regional coding and differences in international licensing. The artistic significance of this release strategy only truly succeeds if it’s universal. It’s all or nothing. Cinephiles ambitious enough can and will find ways around region-blocking, lessening the ultimate impact of the film’s intentional inaccessibility. The question, then, is whether the attempt at creating the experience of sensorial immersion, exclusivity, and temporality, is worth the expense of potentially large amounts of people not being able to ever view the work.

Weerasethakul’s work is notoriously difficult to pin down. His movies are cryptic and layered with complex concepts that are expressed through abstract methods. They tend to benefit from repeated viewings, with their meaning becoming more solvable when returned to. With Memoria itself remaining elusive to all those unwilling to follow the film on tour like roadies to a rock band, the meaning becomes similarly unobtainable. Perhaps that’s part of the point: to remain shrouded in mystery, just as Jessica’s sound is to her. To generate discussion as to what it means, or if the meaning is even important. As with Weerasethakul’s other films, leaving Memoria feels more akin to waking up from a dream than walking out of a theater.

The biggest problem, though, is its long-term inaccessibility. Independent and arthouse films are infrequently if ever screened in small towns or rural settings, where ticket sales are far less certain. Certain films even skip over entire cities, especially those with smaller populations. Due to the more narrow appeal of these films, theaters in rural or lesser-populated areas are less likely to take the risk of booking them.

Relief from this drought comes from the eventual release on digital or physical formats, during which anybody who wants to see the movie is able to. With Memoria, this inclusion won’t occur. Those without reasonable access to one of the country's larger cities will be left out from the experience, probably permanently. Anybody with safety concerns about returning to a movie theater in continuously uncertain times will be, too. A problem arises that as a consequence cinema, something that should be universally inclusive, will be presented in an entirely exclusive manner.

The idea of being able to see Memoria once and only once is a beautiful idea. It’s a piece of cinematic art that undeniably benefits from being viewed in a theater setting. The images and most particularly the sounds would probably be less effective in any other environment. By making Memoria ultimately unobtainable in the sense that nobody can ever own it, the film’s limited release accomplishes something terrific: it reinvents what it means for a movie to even exist. The problem is that as a consequence far too few will be able to witness it. Sure, it can never be owned, but for many, it can also never be seen. The collateral damage is just too significant for it to make sense.

With its never-ending tour, fans of arthouse cinema can only hope for the film to become accessible to them in the coming months or even years. With two cities under its belt, Memoria is headed elsewhere, to destinations currently unknown. Any movie lover with the opportunity to see it should. It’s a fantastic film. It’s a wonderful transcendental experience from a singular artist to whom no others can compare, but even if it benefits from its elusiveness, from the immersive powers of movie theaters, it suffers significantly from its general inaccessibility. It becomes exclusionary, even elitist, something a film should never be. It becomes like the proverb of a tree falling in a forest: does the film even exist if nobody can see it?